Artificial intelligence will read your mind sooner than you think

Breakthroughs in technology that can decipher ‘neurodata’ are coming fast and we may need protection for our thoughts.

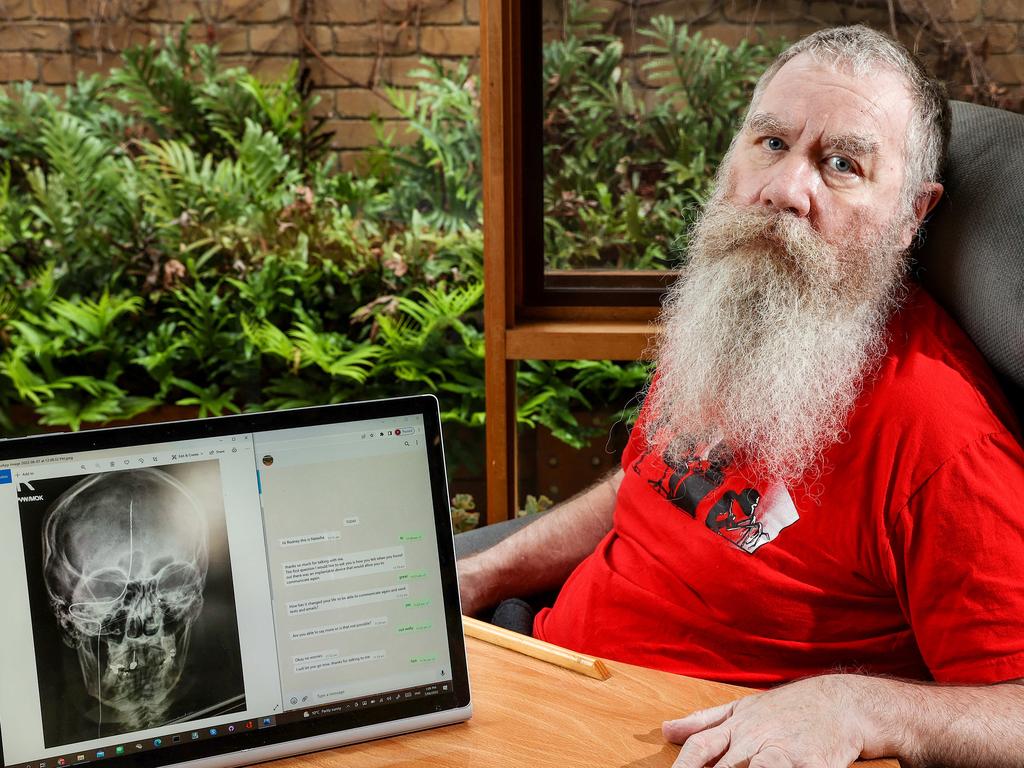

Gert-Jan Oskam is an unassuming Dutchman who 12 years ago was involved in a horrible traffic accident. His spinal cord was badly damaged and his doctors told him he would be confined to a wheelchair for life. He did not walk for a decade.

Yet shortly after I met him this month, he stood up. Supported by a walker, he took several steps.

Those strides were made possible by a set of implants that sit in his skull and monitor the electrical activity of tens of thousands of brain cells.

An artificial intelligence (AI) deciphers this data. In a narrow sense, you could say it reads his mind. It can recognise when he is thinking about taking a step. It then translates this intention into a series of messages that are sent to another implant, at the base of his back. This stimulates his spinal cord, prompting his legs to move.

For Mr Oskam, 40, it has been transformative. He is more independent. His mental and physical health have improved. He told me he’d not thought twice about having a couple of holes drilled into his skull to allow a machine to survey his brain.

But what about the rest of us? Would you allow a computer direct access to your thoughts? The question isn’t as far-fetched as it once was.

Recently I spoke to Professor Bob Knight of the University of California, Berkeley. He and his colleague Ludovic Bellier have used implants to monitor the brains of people while they listen to classic rock.

An AI was able to reproduce a version of the song these subjects heard guided only by the flickering activity of their brain cells. The lyrics were muffled but the track (Pink Floyd’s Another Brick in the Wall) was eerily recognisable and the results have shed new light on how our brains process rhythm and melody.

Breakthroughs like this are coming thick and fast. We’re pretty good at inferring sensory stimuli from brain activity. For example, an AI can predict what your eyes are seeing by analysing MRI scans of your brain.

The United States military has helped fund mind-controlled prosthetic limbs. Then there is Neuralink, a company founded by Elon Musk which says it aims to produce a mass-market “general population device” that would directly connect users’ minds with powerful computers. This year it said it had received regulatory approval to put one of its brain implants in a human for the first time.

Could all of this lead to new kinds of thought crime? The Information Commissioner’s Office, the data watchdog, has predicted that “the use of technology to monitor neurodata, the information coming directly from the brain and nervous system, will become widespread over the next decade”.

It is concerned that employers might try to use such neurodata to assess job applicants or to check whether workers are concentrating at their desks. Neurodivergent employees whose brain waves do not fit a standard pattern might face discrimination, it suggests. It also sees a risk of neurodata being hacked, that devices could be built to “reveal thoughts that might otherwise have been private or meant to be edited before sharing”.

Safeguards seem prudent. There is no explicit description or definition of “neurodata” under the UK’s general data protection regulation or other such legislation. Perhaps there should be. Data connected to health, ethnicity and sexuality is already protected.

More broadly, though, unless you get a hole drilled in your skull and an implant inserted in, or directly on top of, your brain, there are limits to what even the most capable AI can divine about what is happening inside your head.

There are systems designed to monitor your brain from the outside which you wear like a helmet. I tried one that let me play a simple computer game with my mind. But the signals that make it through your skull are muffled. (The game was very dull.)

Compared with a proper implant, it is the difference between watching a football match from inside the stadium and trying to follow it from outside by listening to the roar of the crowd.

Even if you were keen to get an implant, if the aim was to share access to your inner monologue we wouldn’t really know where to put it. Oskam’s system works well in part because the motor cortex – the bit of the brain that directs movement – is nice and accessible, a strip of matter that sweeps across the top of your head. We know its function, and that activity in different sub-regions precedes the movement of different limbs.

By comparison, the networks of brain cells that give rise to abstract thought remain mysterious.

According to Andrew Jackson, professor of neural interfaces at Britain’s Newcastle University, one big open question is whether your brain works exactly like mine does. Voice recognition systems can be trained to recognise voices because all voices sound alike, more or less. Whether the same is true for brains we don’t know.

For an AI truly to tap into your mind, perhaps it would have to be tailor-made for you. And perhaps it would take a human lifetime to train it to be useful.

Or perhaps not. Maybe an AI is being developed in a lab in California or Beijing that will crack what philosophers call “the hard problem of consciousness” and lay bare the mechanisms that render experience from matter.

Until then, though, it is worth remembering how much Big Tech already knows about you. Our interactions with social media, the things we plug into Google – these are far more useful for inferring your thoughts than even the most sophisticated neurotechnology, Jackson says.

So if you want to protect the contents of your mind, start with guarding your browser history. And don’t let anybody drill a hole in your head.

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout