Anthrax in the fridge, vials of plague; inside Porton Down

Inside Porton Down there are enough pathogens to kill hundreds of thousands of people. The centre is now playing a key part in the battle against coronavirus.

Through a labyrinth of airtight doors, in the “suited” laboratory at Porton Down’s high-containment microbiology facility, there are enough pathogens to kill hundreds of thousands of people. The abbreviations for the bacteria that make up anthrax – Ba – and the plague – YP – are scribbled in marker pen on a label attached to a refrigerated container.

Sars-Cov-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, is also sealed inside.

This 7,000-acre site in the Wiltshire countryside – world-renowned for its research into chemical weapons and deadly diseases – has become a key part of the battle against the coronavirus. These stocks, which will be destroyed at the end of the day, are kept in plastic biojars – leak-proof pots used to store infectious substances. Scientists carry out drills to prepare for the accidental release of micro-organisms but so far nothing has escaped the labs.

Professor Tim Atkins, who has worked at the defence research establishment since 1996, is standing near a yellow sign with the warning “caution dangerous chemicals” below a pictogram of a skull and crossbones.

“The micro-organisms and the chemicals are probably the most dangerous substances known to man,” he says, without emotion.

The Times is the first newspaper to be allowed in some of the most secure laboratories at the site, which is developing measures to counter chemical and biological weapons and is under 24-hour protection.

Since the pandemic began last year its scientists have focused their efforts on tackling the virus and are designing new techniques to save lives.

Each officer outside the building is equipped with a Taser and a Heckler & Koch MP7, a cross between a sub-machinegun and a carbine that is used by US navy Seals. It was the weapon of choice in the successful 2011 mission to kill Osama bin Laden in Pakistan.

There is no doubt what is at stake should an adversary or criminal gang penetrate the many layers of security, described as similar to an onion by a scientist hosting our visit.

“The first time you hold plague in a vial, and you look at that vial, which is five millilitres, and you understand that the number of infectious doses in that is large – it’s enough to kill hundreds of thousands of people. I think that really does land with people and they understand what they’re handling and the risks associated with doing that,” says Atkins, a microbiologist who is the technical lead overseeing research.

“The same is true of some of the highly dangerous or highly hazardous chemicals that we handle here. Those chemicals have been developed specifically to cause harm to humans.”

Scientists at Porton Down have helped in the national effort against the coronavirus in all sorts of ways. Early on in the pandemic they rapidly manufactured a liquid to test the effectiveness of face masks for medics and care workers after there was a national shortage. The sprays, made of a strong-tasting fluid, help medics to determine whether they are properly fitted and able to resist droplets from patients.

Teams also tested a dozen different methods to speed up the sanitising of ambulances, in some cases reducing the cleaning time from an hour to about ten minutes. The solutions involved the use of rapid gas-release systems and disinfectant sprays.

They have now shifted their focus to researching novel ways to find out if those who catch the virus will go on to suffer multi-organ failure and sepsis.

Other experts are using a new artificial finger to test the extent to which the coronavirus is transmitted via surfaces.

Amanda Phelps, a defence scientist, is looking at how different disinfectants affect the spread of the virus and which ones are most effective at killing it. Wearing a yellow lab coat and disposable green nitrile gloves, she explains how she has to go through multiple procedures to ensure the laboratory is decontaminated. “It’s not something that any scientist would be complacent about,” she says. The 45-year-old virologist has worked with a host of hazardous viruses, including ebola, during her 20-year career at Porton Down.

Before she can handle the coronavirus a “witness” must confirm that she has carried out all the correct safety measures. Only then can she insert her hands into a second layer of thick rubber gloves inside a sealed cabinet that has been cleaned with formaldehyde.

One of her colleagues, Emma, who cannot reveal her surname for security reasons, is interpreting the data from COVID-19 tests taken by troops before they go overseas or return home.

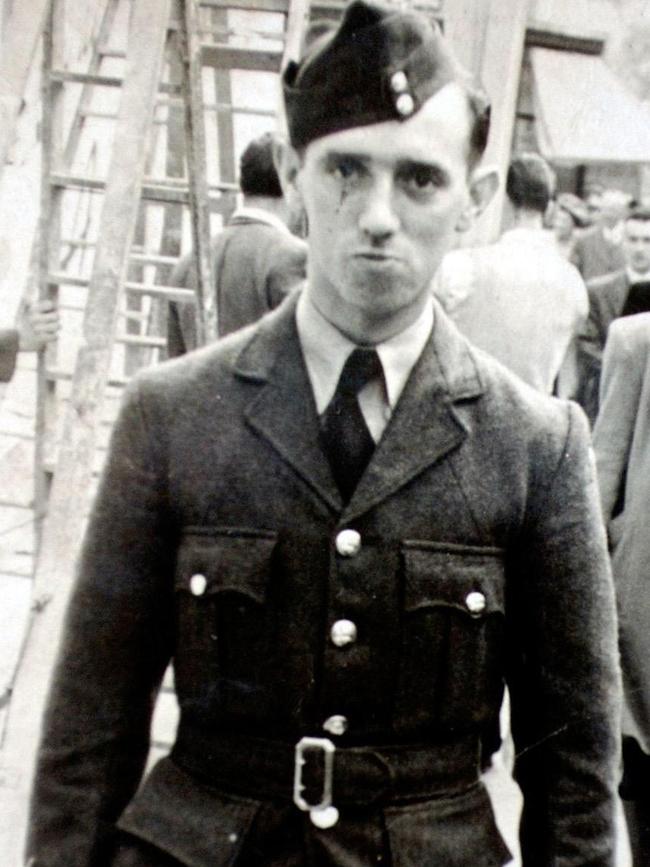

Porton Down, properly known as the Defence Science and Technology Laboratory (Dstl), was founded in 1916, making it the oldest chemical warfare research installation in the world. For decades the secrecy that surrounded the site fed rumours about its experiments. These were exacerbated by the death in 1953 of Leading Aircraftman Ronald Maddison, a 20-year-old human guinea pig who participated in tests of the sarin nerve agent and died foaming at the mouth after having the liquid dripped on to a patch on his arm.

In 2006 an official report concluded that hundreds of servicemen were subjected to unethical chemical experiments at Porton Down before the Second World War and throughout the Cold War. Many of the servicemen who volunteered thought they were part of trials to treat the common cold.

Since these experiments, a great deal has changed in terms of law and ethics and the laboratory has decided to open its doors. Mice are still used for tests at the site but only as a last resort. A small number of rodents were used recently in experiments with the coronavirus to look at therapeutics before being disposed of in the basement.

Asked about the dangers of working in the laboratories, Atkins, who has co-ordinated Dstl’s response to the coronavirus, says: “The pathogens will kill you. If you look at plague, that has killed a lot of people. But of course to kill you, they have to be able to infect you and you can see around you that we invest a large amount of money in engineered control systems, in our training, and in our people, in their qualifications to ensure that we can handle those pathogens safely and of course we’re not exempt from any UK laws or legislation.”

Porton Down has four categories of laboratory, rated according to the virulence or lethality of the pathogens they hold, Atkins explains as he takes us on a tour of the ground floor. Viruses such as anthrax and Sars-Cov-2 are in level 3. The most dangerous pathogens – “things that can kill you instantly” – are in the level 4 lab.

Level 4 labs are found through a series of heavily sanitised nondescript corridors, similar to those in a hospital, and ultimately a set of heavy red doors. Those working on the pathogens here have to wear red surgical scrubs, as opposed to yellow lab coats. When the scientists finish their work, it is imperative they shower before stepping outside.

Only 45 members of staff out of a total of 4,500 are allowed to handle the pathogens in levels 3 and 4.

Around Atkins’s neck is a lanyard decorated with pins, including a commendation for his work on the nerve agent novichok after the poisoning of Sergei Skripal and his daughter Yulia in Salisbury in 2018. Atkins was part of the team that identified the source of the toxin, which Britain believes was used by two Russian spies. “In my career I never predicted that I would see a chemical weapon used in a city close to Porton Down, so I think probably nothing will surprise me now,” he says.

Scientists carry out research into chemical weapons in a separate building next door. Although Britain ended its offensive chemical and biological weapons programs in the 1950s, Porton Down still produces small stockpiles for research to enable scientists to develop medical countermeasures. “We take the chemicals including nerve agents that we know represent a threat to humans and develop protective systems against those,” Atkins says.

Have the scientists here saved lives? Atkins thinks so. “I think if you took some of the advice we provided to the emergency services during the novichok incident, I would like to think we stopped more members of the emergency services becoming ill.

“Now that’s quite sensitive because clearly some of them were badly affected. So we weren’t as successful as I would like to have hoped, but I think we did prevent injury certainly and probably death and I think we’ve probably done that on more than one occasion.”

The Times