Ahmed Zaki Yamani: The man who helped shape Saudi Arabia’s oil fortunes

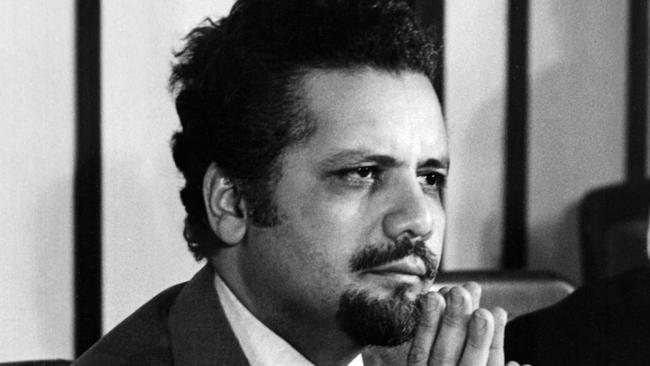

Ahmed Zaki Yamani was the Saudi oil minister for almost 25 years, engineered the 1973 OPEC embargo and survived a kidnapping and threats of death by Carlos the Jackal.

Ahmed Zaki Yamani was standing next to King Faisal of Saudi Arabia on March 25, 1975, when the king’s nephew drew a .38 pistol from under his robes and fired three times, leaving Faisal dying in Yamani’s arms.

“The blood was everywhere,” he recalled.

Nine months later Yamani, an energetic man with a well-groomed goatee and darting eyes, again looked down the barrel of a gun when he was one of 11 ministers taken hostage in Vienna during a meeting of the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). They were seated around a conference table when a group of terrorists burst in.

“The Iraqis and Algerians were in the middle of arguing when suddenly we heard gunfire,” Yamani said. “Masked men stormed the conference room, firing machineguns up into the ceiling, shouting at us to lie down on the floor … When the firing stopped someone asked in English if Yamani was in the group.”

Their leader was Ilich Ramirez Sanchez, better known as Carlos the Jackal.

“After a while Carlos took me to a dark room and told me that I would have to be assassinated along with the Iranian minister,” continued Yamani, who was given 30 minutes to write a will.

“He had nothing against me personally, just against the policy of my government. He told us he was a Marxist, but he looked and behaved like a capitalist, well dressed in a beautiful Pierre Cardin dark leather jacket and a pale blue silk turtleneck.”

Austria allowed the terrorists to leave with their hostages and they flew around the Middle East until Carlos accepted a $US20m ransom in Algeria, and Yamani was freed.

Yamani, who sometimes wore traditional Arab dress, other times a smart Western suit, had been Saudi oil minister since 1962 and was the most media savvy of Arab politicians. Urbane and articulate, he could speak English and French and was a formidable negotiator.

As the leading strategist within OPEC, Yamani was considered responsible for engineering a near-quadrupling of international oil prices during the 1973 Arab boycott of oil exports to countries deemed too favourable to Israel during the Arab-Israeli war.

The embargo triggered a crisis, plunging Western economies into recession, and seemed to make Yamani one of the most powerful men in the world, while also marking Saudi Arabia’s emergence as an oil-market superpower. He travelled the globe, explaining the Saudi view. “Do you know how much we pay for a barrel of mineral water?” he said. “Double what you pay for a barrel of excellent crude oil.”

Yamani also oversaw the nationalisation of what was to become the state oil company, Saudi Aramco. In 1972 he moved cautiously to wrest control over vast Gulf oil reserves from Aramco, the consortium of four American oil companies that had been running production in the country since a concession agreement signed in May 1933. The Saudi government bought 25 per cent of Aramco in 1972, increased its holding to 60 per cent the next year and took full ownership in 1980.

In the years after the embargo, believing it was in Saudi Arabia’s long-term interest to prolong global dependence on affordable oil, he resisted demands from Iran and Iraq for big price increases, fuelling their allegations that he was pro-American. When the 1979 Iranian revolution led to a new energy crisis, he ensured that Saudi Arabia increased production to offset in part the loss in Iranian oil and lessen the panic buying.

Yet he had long foreseen that OPEC states would one day have to deal with competition from new sources of energy. It was a point he reiterated in 2000. “Oil will be left in the ground,” he said. “The Stone Age came to an end not because we had a lack of stones, and the oil age will come to an end not because we have a lack of oil.”

Ahmed Zaki Yamani was born in Mecca in 1930, the youngest of three children. His father was Hassan Yamani, an Islamic scholar and judge of Yemeni descent. At that time Saudi Arabia did not exist and Mecca was a city of camels and unpaved roads. He was a commoner and the title sheik was an honorary one.

After studying engineering at the University of Cairo, where the future PLO leader Yasser Arafat was a fellow student, he went in 1954 to continue his education in New York.

A friend teased him that America was full of homosexuals, but he could spot them by their red ties. At his hotel, Yamani was alarmed when a man in a red tie came over. Flustered, he buried his face in tourist brochures, but saw the funny side when the man whispered discreetly: “Excuse me, sir, your flies are undone.”

He lived alone and struck up an unlikely friendship with Nat King Cole, frequently visiting the small club where Cole appeared. Whenever he entered, the singer would strike up Hajji Baba.

In New York he met Lailah Faidhi, an Iraqi student taking a PhD in education. By the end of the year they had married. They moved to Massachusetts, where he enrolled at Harvard Law School. They had two daughters, Mai, an anthropologist, and Maha, a lawyer, and a son, Hani, who published To Be a Saudi (1997), calling for political reforms.

The marriage was dissolved and in 1975 Yamani married Tammam al-Anbar, a biologist by training, who survives him with their five children: Faisal; Sharaf, an investment manager; Sarah, a trustee of the Woolf Institute in Cambridge; Arwah; and Ahmad.

According to Yamani: The Inside Story (1988), by Jeffrey Robinson, he also adopted a Malaysian orphan who was brought up by his mother.

Back home, Yamani came to royal attention. “I was working for the government as a legal adviser in the tax department and the oil department, and I was writing in a lot of newspapers,” he recalled. “King Faisal asked me to come to him. He was reading my articles. I think he liked them.”

When Faisal was shot dead Yamani shouted at the king’s bodyguards not to kill the gunman, who was later convicted of regicide and publicly beheaded.

Yamani would rise early to pray. He flew in private jets, owned homes in London, Surrey and Geneva, kept several large residences in Saudi Arabia, and was said to be worth $US500m. “Not really enormously rich; no, honestly,” he protested. “I am a good long-term investor, cautious, moderate. I don’t gamble. I don’t drink. I don’t care for nightlife.”

After 24 years as the public face of Saudi oil policy, the charismatic Yamani was removed in 1986 by Faisal’s brother, King Fahd, learning of his dismissal from the television. He was placed under virtual house arrest and for a time he was not permitted to leave the country.

Later he founded the Centre for Global Energy Studies, collected Islamic manuscripts and perfected the Arabic skill of making perfume.

Visitors to his Knightsbridge apartment were served homemade chocolates. “I make these myself,” he told Gyles Brandreth. He travelled with a portable trampoline “to keep the blood flowing” and was one of the first Saudis to keep dogs as pets rather than for hunting.

After the OPEC attack Yamani kept a retinue of former-SAS bodyguards. “I was sure as I said goodbye to Carlos that he would kill me sooner or later,” he concluded. “Afterwards it wasn’t easy to adjust. It seemed that I was laughing and acting as normal on the outside, but inside I was in turmoil.”

Obituary: Sheik Ahmed Zaki Yamani. Saudi oil minister, 1962-86. Born: June 30, 1930. Died: February 23, 2021. Aged 90

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout