After years of tolerance, Xi cracks down on artists who mock Mao

The arrest of sculptor Gao Zhen proves that China, never liberal but once having become more tolerant, is changing yet again.

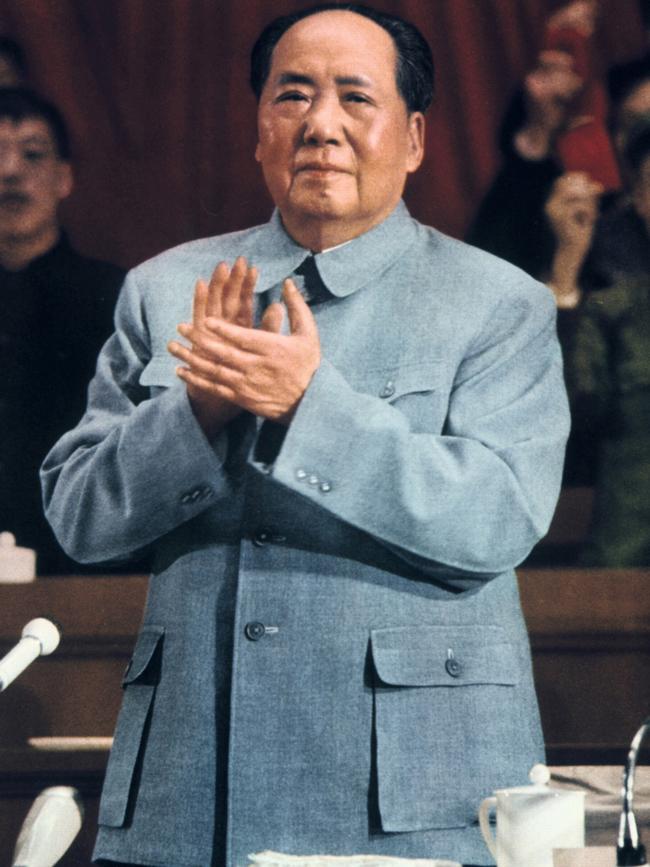

One surprise was that the Gao brothers got away with it for so long. Their smooth, strange sculptures of Mao Zedong in poses by turns violent and humiliating were a carefully thought-out challenge to the Chinese Communist Party, which still officially venerates him.

Yet for years they continued to work from their studio near Beijing, travelling more or less freely to international exhibitions.

“We tried not to think about the question of whether we were allowed to do this work or not,” Gao Qiang, 62, says from New York, where he lives.

“We simply assumed we were free, and believed we should be free to do any artwork, and at the same time we prayed for God to keep us safe.”

The second surprise was that the party should decide to move years later, when the brothers were no longer living in China. Gao Zhen, 68, finally was arrested last month when he returned home to visit relatives with his wife and son. He remains in custody. His detention was a warning, Gao Qiang says, and a sign of how China, never liberal but once having become more tolerant, is changing again.

“The space for freedom in China has shrunk a lot,” he says.

The Gao brothers, a sort of Chinese Gilbert and George who worked together and looked uncannily alike despite their age difference, emerged from China’s turbulent, semi-secret explosion in art and writing in the 1980s.

Mao had died and Deng Xiaoping was slowly opening up the country and the economy, although there still were “campaigns against spiritual pollution”. A new generation of artists had grown up in the shadow of the Cultural Revolution, an experience they were determined to express artistically. The Gaos’ father had been killed as a suspected right-winger in 1969, although the circumstances in which he was beaten to death were never clear.

For many people such as the Gaos, the Tiananmen Square protests and massacre were also a focal point, one that proved politically to be an interruption rather than a full stop in their careers. The Gaos were becoming well known in China but as the ’90s progressed they joined the forefront of a new radical wave, influenced by the Young British Artist movement led by Damien Hirst and Tracey Emin, creating disturbing pieces, many a twist on Mao-era propaganda.

One sculpture showed a firing squad, each rifleman bearing the placid face of Mao as he appears in official portraiture, executing a figure of Christ. Another showed Mao kneeling in apologetic self-humiliation, expressing the remorse he never showed in life.

Attempts to show the works in public often ended in failure but the Gaos survived.

“Although we encountered many big or small troubles due to the creation and exhibition of sensitive works, generally speaking, really, thank God we were OK,” Gao Qiang says.

Artistic freedom reached a limited peak in the years between Beijing being awarded the 2008 Olympics and the Games themselves, as the city became one of the most fashionable in the world. The modern art community, as an expression of this, was too valuable to persecute and its unofficial headquarters, a redundant giant missile factory in northeast Beijing called Factory 798, became a tourist mecca.

Modern Chinese art sold at auction houses around the world, first for tens of thousands of dollars, then hundreds of thousands and finally millions.

But there were always limits. “Even during this era which superficially might have seemed quite permissive, there was never a time when artists and writers weren’t being arrested,” says Ma Jian, one of China’s best-known writers of the period, now living in London. Ma’s books exploring his country’s modern history – such as Red Dust, a novelist’s record of a three-year journey around Deng’s China – brought him a worldwide audience.

After 1989, Ma lived in Hong Kong for a decade but he was still able to return to Beijing. After the Olympics, however, the repression became more open. Pretexts were found to arrest the most outspoken artists, such as Ai Weiwei, who had used his prominence to speak up for families whose children had been killed owing to shoddy and corrupt building practices in the Sichuan earthquake in 2008.

The ascent to power in 2012 of Xi Jinping, whose father, while persecuted in the Cultural Revolution by Mao, had also been a close lieutenant at one stage, closed the space for historical introspection further. One by one, artists and writers moved abroad.

Ma, who was already living in London, found it harder to return home: in 2013, when his mother was dying, he was stopped from entry from Hong Kong to visit her. He was eventually allowed in, under close monitoring, for her funeral, his last visit home.

The Gao brothers, meanwhile, were moving freely if circumspectly between New York and Beijing. But in 2021 Xi introduced a new law that seemed to target the Gaos and artists like them: it became an offence to “dishonour China’s martyrs and heroes”. Mao, clearly, was to be regarded among them, despite the millions who died under his rule.

“Mao indeed made countless people heroes and martyrs, but he himself is not a hero or martyr,” Gao Qiang says. “I don’t remember when he has ever been awarded the honorary title of hero or martyr.”

More shocking, it became clear, not least from Gao Zhen’s case, that the law was to be applied retroactively. He was in his studio’s living quarters with his wife and son when the police arrived, surrounding it before taking him and its artistic contents away. He remains in detention, and although his lawyer and his wife have been allowed to visit him, there is no sign that he will be released soon.

His wife also was stopped from leaving the country. In cases such as that of Liu Xiaobo, the dissident Nobel prize winner who died of cancer in 2017, and other figures with an international reputation, spouses often are held under virtual house arrest to prevent them publicising cases in the international media.

Ma has organised an open letter of protest, demanding Gao Zhen’s release. It has the signatures of prominent writers and artists, about half still in China – a brave step.

“We have reached a point where if we continue to remain silent who knows who will be next,” Ma says. “If another artist is arrested and disappeared, when it is your turn, who will speak out for you? The Gao brothers are very important artists who think very deeply about the Chinese situation and are brave enough to tackle the most sensitive taboos.”

As for Gao Qiang, he made his choice the minute he left China for the last time seven years ago. Unless and until something changes, which looks remote, he will not revisit the land of his birth and his father’s death.

THE TIMES

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout