After Voldemort, Ralph Fiennes rejects the dark side

The celebrated actor and director has shown off his extraordinary range since swearing off “bad guy’’ roles.

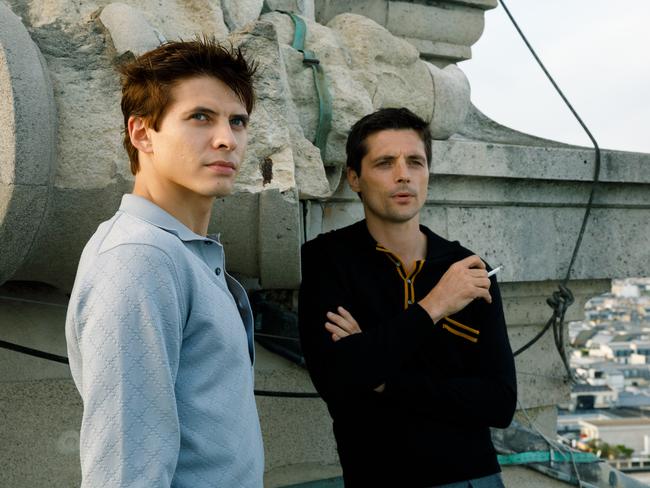

Ralph Fiennes’s The White Crow, the actor’s third film as a director, is as fine a portrait of an artist as a young man as you will find outside the pages of James Joyce.

Set in Paris in 1961, it is the story of the defection of Rudolf Nureyev from Russia, the climax of the Kirov Ballet star’s belligerent growing up and a big publicity coup for the West.

Its writer, David Hare, who has done a job as brilliant as The White Crow’s director, has said he loathes the idea that Nureyev’s defection was a balletic “leap to freedom”. At the time, he points out, there was optimism in Russia after the death of Joseph Stalin and the accession of the more liberal Nikita Khrushchev. It is true, certainly, that the man Fiennes plays, Nureyev’s teacher Alexander Pushkin, was no tyrant. Indeed, it is vaguely upsetting to see the much lusted-after leading man who, two decades ago, was the seducer in The English Patient, now at 56 play a bald professorial type, cuckolded by his protege — although the real seducer in this case was, it seems, Pushkin’s wife, who cajoled the mostly homosexual Nureyev into her bed.

“Alexander was very kind and very, very gentle,” Fiennes says. “People talk about his technique, which was to let the students discover their own mistakes. I’ve seen ballet classes where the teacher literally comes and forces the arm and turns the head and wrestles with a student’s body.”

Fiennes agrees with Hare that it was claustrophobia, rather than tyranny, that Nureyev was fleeing and that his defection was a spur-of-the-moment decision prompted by the heavy-handedness of KGB minders alarmed at his carousing in Paris. Still, the urge had surely been building. “Subconsciously, for him there was a world elsewhere,” Fiennes says, quoting from Coriolanus, which he has starred in and directed for cinema.

Nureyev’s “leap” is performed at Le Bourget airport in front of a scrum of reporters, whose colleagues would pursue the dancer right up to his death from AIDS in 1993, aged 54. Perhaps the film suggests that the dancer trades one form of surveillance for another? Fiennes barely concedes the point even though his own private life — in 1996 he left his wife, Alex Kingston, for Francesca Annis, his co-star in Hamlet, almost 20 years his senior — has suffered its share of scrutiny.

A newer form of Western tyranny seems to disturb him more. In recent weeks he has offered his support to Liam Neeson, his Schindler’s List co-star, after Neeson said in an interview that he had once wandered the streets with a cosh hoping to be attacked by a “black bastard” so he could avenge the rape of a woman close to him. Fiennes also has stood firm by Michael Colgan, a former director of the Gate Theatre in Dublin, who has been accused of bullying and sexual harassment during his tenure. In the first case, Fiennes says Neeson was attempting an honest confession. In the second, to be accused is not invariably to be guilty.

“I think there’s a kind of political correctness which has its strength but is in danger of becoming its own sort of totalitarianism,” Fiennes says.

It is harder to argue the case for Sergei Polunin, the Ukrainian dancer with a supporting role in The White Crow who in January was dropped from a ballet in Paris after posting rants on Instagram, but Fiennes says he was a joy to work with. “Basically, I ignore all the stuff that he said because I believe there’s the noise the human being can make and then there’s who they truly are as a person, and I think Sergei is a good man, a kind man.”

Fiennes can make a bit of noise in his private life (in 2007 an air stewardess claimed she had inducted him into the mile-high club). “I’ve been guilty of shit,” he agrees. He is less ready to concede that his description of “the unpleasantness” of the young Nureyev as he looked to “create” himself may have once applied to him. “I’m uncomfortable saying an overt yes to that. I connected with aspects of his hunger to learn, I suppose, his hunger to absorb.”

Fiennes’s self-creation remains a fascinating subject. His career looked set to be in art until, enrolled at Chelsea College of Arts, he noticed a young New Zealand painter and the “fury” he had about his vocation.

“I thought, ‘He is driven and I’m here painting that bowl of fruit, but I don’t know what I’m trying to say.’ I had acted at school and there was some moment at college when the penny dropped and I thought, ‘No, I want to be an actor.’ It suddenly became very clear to me, certain.” Was there fury about his acting? “I think there was a bit. There was a real sort of determination, but I remember one audition at one drama school. I came out with this RP voice and I think they thought, ‘Who is he? Is he pretending to be a Shakespeare actor?’ I felt maybe I wasn’t the kind of actor that was cool at the time.”

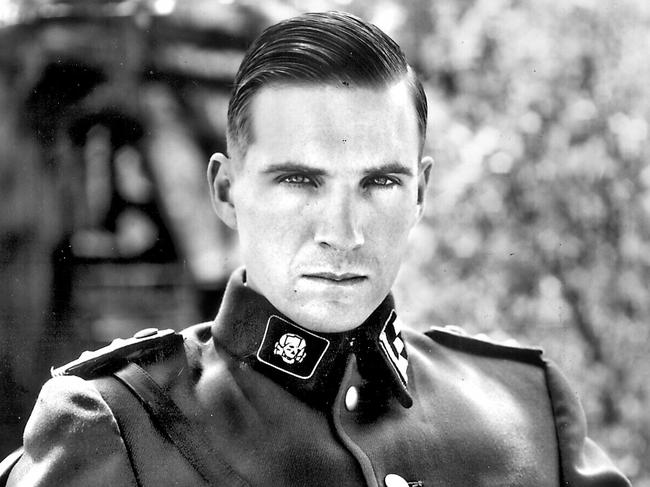

London’s Royal Academy of Dramatic Art recognised the real thing. Leaving in 1985, he was quickly taken up by the Royal Shakespeare Company and the National Theatre. By the time I last interviewed him, in 1995, he had already been nominated for an Oscar from his remarkable portrayal of the concentration camp commandant Amon Goeth in Schindler’s List, and was about to play Hamlet in London — which was where he would fall in love with Annis, who was playing the prince’s mother. There was no doubting his greatness.

Of his range, however, there was less inkling.

From Goeth, we knew he could play a particularly nuanced kind of evil, but who could have predicted his terrifying box-office turn as Voldemort in the Harry Potter films?

“I did actually say to my agent, after Voldemort, ‘Please don’t send me any bad guys. I’ve done that now.’ And I don’t think I’ve broken that promise, unless you count David Hare getting me to play his version of Tony Blair in Page Eight.”

A consequence of that resolution was our discovery that Fiennes could be wickedly funny on film — as the suavely savage Gustave in Wes Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel and then that grab-bag of ego, the music producer Harry, in A Bigger Splash. However, this is also a serious actor who learned Russian for the movie Two Women and speaks it beautifully in The White Crow, indistinguishable from Russian cast members speaking their native tongue. His BAFTA-nominated directorial debut with Coriolanus in 2011 was followed up by an impressive Dickens movie, The Invisible Woman.

There is an off-the-peg explanation for Fiennes’s overachievements. As a child, he had to compete with his siblings for attention, for love, and to impress.

“I was the eldest of six and I probably had a little bit of special treatment, being the eldest, and then felt the competition coming up behind,” he says.

He says his mother, Jennifer Lash, a writer known as Jinni, who was married to Mark Fiennes, a farmer turned photographer, inspired her brood with her love of words and performance. Two of his sisters, Martha and Sophie, became filmmakers; one brother is a composer; and another is Joseph Fiennes, the actor.

“But it was frantic. She often felt huge distress. She wanted to write, and sometimes the pressure and the strain and the frustration of not being able to write, not having the time to write, the peace and the space to write, would explode, but the love was always there, incredible love.”

Jinni, who published her first novel at 23, died of cancer aged 55, when Fiennes was 30. He says he still feels her presence, although that could just be his “own need to feel that something”.

Does he dream about her? “Sometimes. My father too. What’s so weird is my mother died in 1993 and my father died in 2004 and yet somehow in the brain they’re restored. In the dreams, if they come, they’re completely clear, completely present and as they were. Somehow the brain has stored the memory of the voice, the person.”

Do friends ever say to him that his career has been incredibly Oedipal? I am thinking not just of Hamlet and his leaving a wife of his own age for his Gertrude, but the mother-son dynamic of Coriolanus.

“Yes, people have commented on that, and I shouldn’t be ashamed of it. I mean, Oedipal is probably how we’re wired as the sons of mothers. I don’t feel any awkwardness about there being an Oedipal element in one’s self. I think that’s quite healthy. It’s part of who you are.”

Hare has said of Fiennes that he likes to surround himself professionally with people who love him. I wonder whether film sets and theatre companies are his substitute families. “I think you’re in a kind of parental mode as a director, and that is your family. As an actor in a company, you’re less parental, although if you’re possibly in a leading role, there is a leadership element.”

I like the idea that he joins families of actors and, now that he is older, he becomes their father. “Yes, although I haven’t consciously thought I’m achieving parenthood that way,” he begins. And then thinks of Oleg Ivenko, the 22-year-old Ukrainian ballet dancer from whom he has conjured up a light yet intense performance in the lead role in The White Crow.

“Oleg was a totally inexperienced actor. That was a version of creative parenting, guiding him through the requirements of a feature film and a main role.”

THE TIMES

The White Crow is in cinemas next week.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout