After two days of explosions, how will Hezbollah retaliate?

Lebanon’s Hezbollah had cultivated the aura of a formidable, tech-savvy guerrilla force for decades. But that has all collapsed with an apparent Israeli intelligence operation that has humiliated the Iranian-backed militia.

For decades Lebanon’s Hezbollah had cultivated the aura of a formidable, tech-savvy guerrilla force.

There was the time they hacked an Israeli surveillance drone, giving them advance warning of a special forces operation they then ambushed. Or when they sent their own surveillance drones over Israel, bypassing aerial defences and taking footage of some of the country’s most sensitive sites.

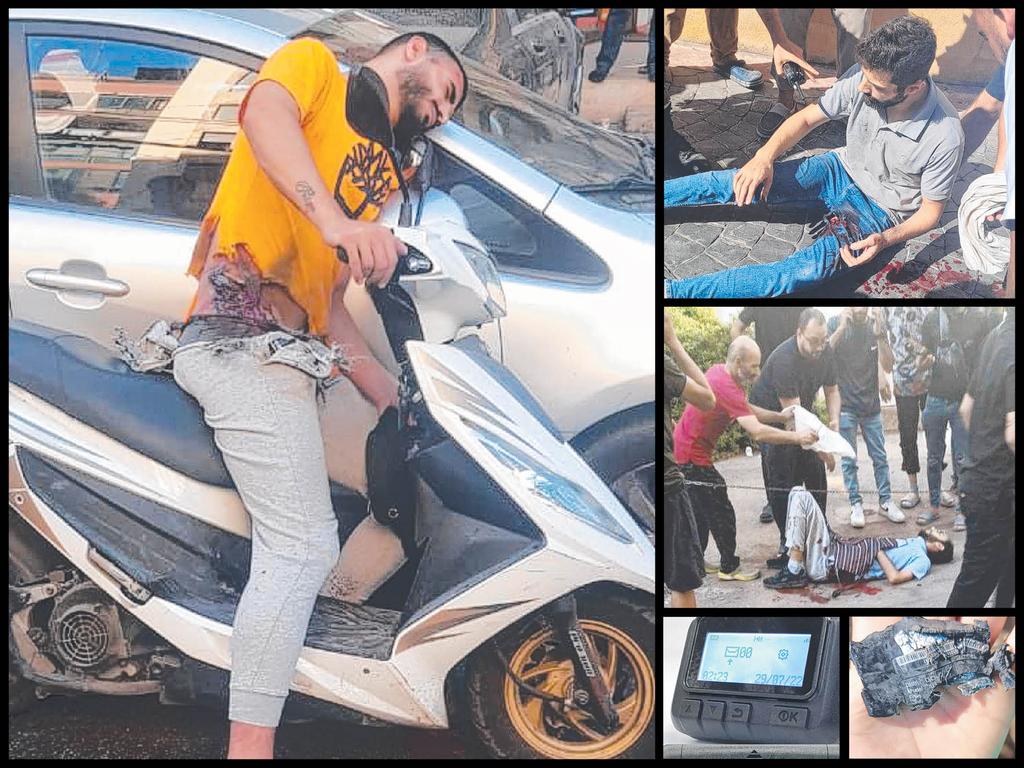

Laptops, phones, doorbells, mopeds, and walkie-talkies are exploding in Lebanon, creating absolute terror among civilians. https://t.co/6KvVhWuICrpic.twitter.com/SDN2LVXC3C

— Russian Market (@runews) September 18, 2024

That has all collapsed with an apparent Israeli intelligence operation that has humiliated the Iranian-backed militia. The operation, which involved rigging thousands of pagers and walkie talkies with explosives, has been described by one Hezbollah commander as the group’s “biggest security breach yet”.

It was a blow that will be felt across the organisation, from commanders to rank-and-file members. The militia’s politicians and bureaucrats were all affected, with every hospital in Lebanon receiving the wounded.

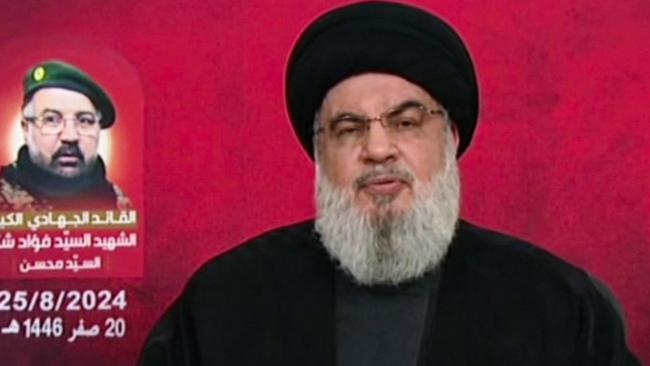

Hezbollah, though, is accustomed to leaders being assassinated. That is par for the course, as Hassan Nasrallah, its leader, said in a speech last month after an Israeli airstrike killed the military commander Fuad Shukr.

Nasrallah, who rose to his position after Israel assassinated his predecessor, Abbas al-Musawi, had said the group must remain calm and calculated in its conflict with Israel, dismissing calls for an escalation that would spark all-out war with Israel after months of low-intensity conflict around the border.

He will now face pressure from within to lash out. But first, Hezbollah’s members will need to regain confidence in their leadership and internal security measures.

They had always assumed that Israel spared no effort to penetrate the group, and earlier this year Hezbollah ordered its members to stop using mobile phones that could be easily hacked by Israeli intelligence and switch to the pagers. These were ordered in bulk, and Israel, as it happened, had rigged them at some point during the delivery.

It was Hezbollah’s biggest failure since its inception in the early 1980s, and one of Mossad’s biggest triumphs in its long-running conflict with the group.

While the operation would have been months in the making, it could not have come at a more dangerous time. Israeli intelligence would presumably have wanted to complete the mission as soon as everything fell into place — the longer they delayed, the more likely it would have been compromised by an attentive Hezbollah technician.

But in recent weeks, the likelihood of an expanded Israeli operation in Lebanon to end Hezbollah’s rocket fire, which has emptied out its northern towns since October, has grown as hopes for a ceasefire in Gaza have faded.

The Israeli military believes its role in Gaza should be coming to an end after decimating Hamas, which sparked the war by killing more than 1,000 Israelis and kidnapping more than 200 in October, and wants to focus on Hezbollah.

The Defence Minister, Yoav Gallant, favours a limited yet punishing operation in Lebanon, one that does not bog down the military against a formidable guerrilla force that also possesses more than 100,000 rockets. Benjamin Netanyahu, the prime minister, is said to favour an even wider operation.

Michael Milshtein, a former Israeli military intelligence officer, said earlier this week that Israel will probably strike deeper into Lebanon, including in the capital, Beirut, while Hezbollah could target Haifa, a coastal city in northern Israel, and cities even further south.

“Both sides will plan a restricted round of escalation,” said Milshtein, who now heads Palestinian studies at Tel Aviv University’s Moshe Dayan Centre for Middle Eastern and African Studies. “But the problem is: you can’t predict what will happen.”

After Tuesday’s operation, all bets are off.

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout