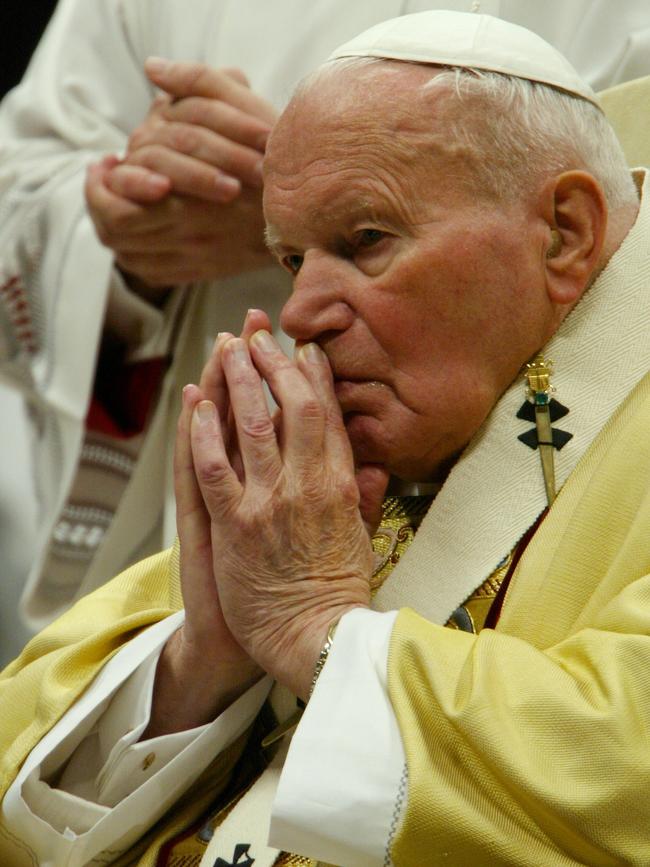

It marks the formal end of a particular dream among Catholics – that the brilliant but defiant engagement of the modern world on behalf of traditional Catholic belief, carried out so successfully by Benedict’s predecessor, John Paul II, could continue under successor popes, who naturally lacked JPII’s personal charisma.

But now the political radicalism, pastoral liberalism and theological imprecision, or, his more severe critics might say, even confusion, of Pope Francis, has also failed over these last 10 years. The seeming radicalism of Francis has seen no Catholic revival.

A new papacy looms shortly. And a new moment of decision for the Catholic Church.

Francis himself is 86, mostly gets around in a wheelchair, has one lung and is in less than robust health. More than once he has hinted that he might follow Benedict’s example and become the second pope in more than half a millennium to resign from the office.

Benedict was the conservatives’ candidate at the papal conclave in 2005. Terms like conservative and liberal are highly inadequate in describing the complex theological, pastoral and personal issues involved in electing a pope. But they are not without meaning.

Benedict, like JPII, believed the church needed to radically change its manner of engagement with the modern world, but in doing this it had to continue to preach the unchanging truths of the gospels and traditional Christian doctrine.

The great cliche of church renewal is “reading the signs of the times”. The conservative says: the signs of the times are difficult and thus we must communicate our beliefs and extend our care much more dynamically; the liberal says the signs of the times are so difficult that obviously some of our teachings are wrong and we need to change these teachings to become culturally relevant.

In that sense, Benedict and JPII were conservatives, embracing change to serve unchanging truth.

Benedict as pope was nonetheless a great disappointment to the conservatives. As a theologian he was without peer, a brilliant, and at times screamingly funny, writer. In his magisterial three-volume biography of Jesus, he deals, in passing, with all the nuttiness of some branches of modern biblical scholarship. He once commented that we would be able to recognise the Anti-Christ when he came, for he would have a theology doctorate from a German university and be the author of a work that was “pioneering in its field”.

Benedict perhaps came too old to the papacy and lacked the energy, ruthlessness and drive to administer the Vatican ship of state effectively. He was well intentioned in responding to the clerical child sexual abuse scandal but not entirely effective. He was sometimes poorly served by his advisers and neither sacked nor overruled them.

But Benedict may yet be a pivotal character in the future of the Catholic Church. He will live now not through institutional reforms but through his prodigious writings, which operate at a unique depth both in terms of understanding timeless Christian truth, and also understanding the Western culture which is rejecting that truth.

Benedict saw that, if the church was to retain its faithfulness to the truth, it would become smaller and more different from mainstream society. It would struggle to occupy the very civic spaces it had itself created.

But, and here’s the rub, there is no meaningful theological alternative to this timeless truth which Benedict championed. The papacy of Francis demonstrates this conclusively. Francis is plainly a loving man and a loyal servant of the church and of humanity. But for radicals he is almost as big a disappointment as JPII and Benedict.

Francis has moved against some church institutions which conservatives value, and politically he’s way to the left, though a pope’s political views carry no religious authority within Catholicism, and he says things that are perplexing and hard to interpret.

But after 10 years of Francis, there are no discernible changes in Catholic doctrine – the church still opposes abortion absolutely, there are no women priests, hell has not been abolished, nor even purgatory, the awesome consequence of man rejecting God figures as large in official Catholic teaching today as it did under either of the previous two popes.

The next pope then, ideally, needs JPII’s energy, Benedict’s intellectual clarity and teaching honesty, and Francis’s pastoral instincts. He is sure to be influenced by Benedict’s writings.

But he will need all that and a lot more. That will be a tall order.

The death of Pope Benedict is a long-awaited but serious blow to conservative Catholics.