George Pell: Pope Benedict was a good pope, but not a great one

Joseph Ratzinger, Pope Benedict XVI, is universally regarded as one of the finest theologians and writers in the papacy’s almost 2000-year history.

Three anecdotes from the years in Joseph Ratzinger’s long life when he was not yet famous, but only infamous in certain circles, throw light on the enigma presented by his personality, capacity, and achievements.

Ratzinger, who became Pope Benedict XVI and later emeritus pope, died on December 31 aged 95.

In 1968 when he was lecturing in Tubingen, near Stuttgart, in Germany, he did clash with radical Marxist students, who, however, did not shout him down, as Catholic theologian Hans Kung alleged. On one occasion after a lecture by the Dutch Dominican Edward Schillebeeckx, he was on a discussion panel which included Kung. He had said nothing until the students began shouting, “Ratzinger must speak”. When he then summarised and analysed the debate for 15 minutes, the chairman announced that nothing more needed to be said and the gathering closed happily.

Almost 30 years later in 1996, he gave the then-Communist author Peter Seewald a long series of interviews on the Church in the world at the end of the millennium. A former editor of German newspaper Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung refused to review this interview of a freelance journalist with “someone”, saying it was out of the question for them. The “someone” was the then-Prefect of the Congregation of the Doctrine of the Faith in the Vatican and, in book form, The Salt of the Earth sold 500,000 copies in 20 languages.

After Ratzinger’s election as Pope in 2005, the publishers of Seewald’s first article were looking for an accompanying photo – 25 photos were rejected because Ratzinger looked “too good”; they did not conform to the hostile stereotype.

Ratzinger was born in the Bavarian village of Marktl am Inn on April 6, 1927. One of three children, he spent his adolescent years in Traunstein, a small town on the Austrian border. He described himself as a Mozartean, and not simply because of his knowledge and love of classical music. His brother, George, with whom he was ordained a priest on June 29, 1951, in Freising, was for many years director of music in Regensburg Cathedral.

Like all his German countrymen, Ratzinger suffered during the Nazi period and once saw his parish priest beaten by the Nazis before celebrating Mass. Towards the war’s end, he was conscripted into the anti-aircraft service.

He wrote a doctorate on Saint Augustine’s concept of the Church, qualified as a university professor in 1957 and then lectured successively in Freising, Bonn, Münster, and in Tubingen during the upheavals of 1968. The following year, he was appointed professor of theology at the University of Regensburg, eventually becoming dean and vice-rector.

He wrote prolifically during his whole priestly life. At one stage, I thought I had read most of his writings and was amazed to see the number and variety of his earlier works, none of which I had read.

The Second Vatican Council in Rome (1962-65), attended by all the Catholic bishops, was the most important event in Church life in the 20th century and Ratzinger was present as a young priest-theologian for all four sessions, appointed as theological adviser to Cardinal Josef Frings, the Archbishop of Cologne.

Although not as well known to students as senior theologians such as Yves Congar, Karl Rahner, Henri de Lubac, and Kung, he was active in the reforming majority movement which prevailed in the consensus-making for the conciliar decrees.

Two complementary and sometimes contrasting themes were predominant among the majority: those who favoured “aggiornamento”, bringing the Church up to date, and those who believed that vitality lay in “ressourcement”, returning to the teachings of Jesus and the apostles as lived and explained in the first centuries. Ratzinger was always prominent in the second group, an explicit disciple of the French Jesuit de Lubac, who insisted until the end that the council was an example of doctrinal development, of evolution and continuity, that did not provoke a rupture from previous Church history, as proposed by the Bologna school of historians, a theory which has made something of a comeback in recent years.

The Holy Father was not a disciple of Thomas Aquinas, although he always acknowledged the massive contribution of Thomism; much less was he a scholastic, never setting out his writings as a clear, dry series of propositions. An Italian curialist pointed out to me that he never studied in Rome as a seminarian or a young priest and he was never interested nor much involved in the intrigues which swirl around the papal court. He stubbornly believed in the goodness of people, although he often, but not always, came to accept the different estimates of his secretaries and friends. For his 40 years in Rome, actively engaged at the centre of Church life, he remained something of an outsider.

In 1972, while still at Regensburg in Bavaria, he was one of the founders of a new international magazine, Communio, which reflected a parting of ways from the line of the Concilium magazine, with its more radical appeal to aggiornamento (modernisation) and the spirit, not the texts of the council.

A destructive revolutionary zeal swept through many parts of the Western world after the council where eventually 30,000 men left the priesthood – vocations to the priesthood and religious life plummeted and Church life imploded in Holland, Belgium, and Quebec. In 1972, Pope Paul VI, who had been slow to grasp the extent of the disaster, announced that the “smoke of Satan had entered the Church”.

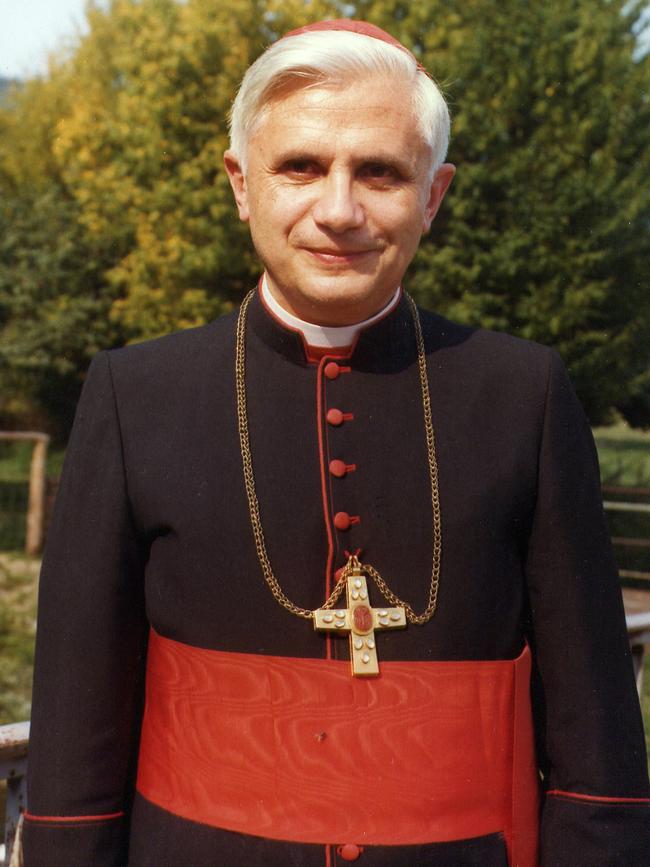

However, it was only on March 24, 1977, that Pope Paul VI appointed Professor Ratzinger as Archbishop in Munich and Freising and then in June created him a cardinal. This was a year before Pope Paul VI’s death, the brief reign of Pope John Paul I, and the advent of the Polish Pope John Paul II. The new Cardinal Ratzinger was an active, pastoral archbishop during his five years in Munich, committed to implementing the Council decrees, not opposing them, as Pope Paul VI desired.

Pope John Paul II appointed him Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, once known as the Inquisition, and he commenced there in February 1982, beginning a brilliant partnership with the Polish pope. They were very different, Polish and German, extrovert and reserved, public leader perhaps mystic and intellectual, and a philosopher and a theologians’ theologian, with an unusual gift for clear and elegant writing. It was here Benedict did his best work, just as some claim Paul Keating was a better treasurer than prime minister and Tony Abbott was Australia’s most successful opposition leader and a less effective prime minister.

The then-Cardinal Ratzinger’s most outstanding achievement was as president of the committee (1986-92) which produced the Catechism of the Catholic Church, on the beliefs of the faithful, a classic which ranks with the authoritative 1566 Catechism of the Council of Trent. As prefect, he was also involved in the drafting of Pope John Paul II’s encyclicals, including the major moral teaching in Veritatis Splendor and Evangelium Vitae. The Marxist substratum in the theology of liberation from South America was exposed and rejected, another important contribution.

He broke with tradition and continued to write while prefect. While it would be untrue to claim that the chief executive of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith published only anathemas (for centuries the pope himself was the prefect), they generally published little outside their rulings; until Ratzinger.

In November 2002, the Cardinal was elected by his brother Cardinal bishops as dean of the College of Cardinals, preaching his famous sermon at the funeral mass of Pope John Paul II, denouncing the “dictatorship of relativism”.

On April 19, 2005, he was elected pope, the 265th pope, successor of Peter, taking the name Benedict XVI after the founder of rules-based Western monasticism, which provided one of the cornerstones of the Western civilisation in which we still live and which is being steadily eroded.

The new pope continued to write and teach at a level which was historically rare among popes and senior ecclesiastics, as evidenced in his encyclicals Caritas in Veritate, Spe Salvi, and Deus Caritas Est, his discourses to the British and German parliaments, and especially his three volumes on the life of Jesus Christ.

In countries as different as Poland, the United States and Australia, his teaching won over the majority of the young lay Catholics, a minority in their cohorts, who opted to continue to live as Catholics. The changed Church circumstances of recent years have only deepened these Benedictine loyalties. He is loved and has inspired many vocations.

This Mozartian pope understood well the centrality and importance of the liturgy in the life of the Church, the celebration of Mass and sacraments with faith and reverence. Whenever Church life has collapsed, so has liturgical discipline with the official Eucharistic texts abandoned or mutilated and the Sacrament of Penance banished.

He re-established the legitimacy and availability of the Latin Tridentine Mass in 2007 so that each priest has a right to celebrate the “old Mass”. This has spread, wider and faster than most expectations, and in France, half the number of seminarians preparing for priesthood follow the Tridentine rite. Pope Francis through his letter Traditionis Custodes is attempting to curb if not quash these enthusiasms.

Pope Benedict also established an Anglican Ordinariate, with its own English language rite derived from the Anglican ceremonial for Anglican priests and laity who converted to Rome – “crossed the Tiber”. Hundreds of priests came across. This was ecumenically sensitive, but ecumenical dialogue and cooperation have continued.

He did good work in the battle against paedophilia and dealt effectively with the corrupt founder of the Legionaries of Christ, although he was regularly under attack from the secularising forces. His speech at Regensburg exploring the links between Islamic teaching and violence eventually produced orchestrated waves of protest, ironically validating his central thesis. His attempt to improve relations with the schismatic Society of Saint Pius X was mismanaged.

The Holy Father did not have much interest or aptitude for governance, rarely meeting with most of the curial heads, leaving that dimension of his role largely to his secretary of state, with long-term unfortunate consequences. The papal household itself was somewhat dysfunctional and thousands of documents were leaked to the press by Paolo, the butler, probably in a bizarre attempt to help the pope.

Some progress was made financially, although the then-Monsignor Vigano’s reforms were not supported. Significantly, Pope Benedict did commission a secret report on corruption in the Vatican, which has never been published, was not made available to the Conclave which elected his successor, but was consigned to Pope Francis.

My personal conjecture, which is not supported by evidence, is that when Benedict saw the report, he concluded that he did not have the organisational capacity, nor the energy at 85 to cleanse the Vatican stables. Whatever his reasons, he resigned from the See of Peter in 2013, the first such resignation since that of Pope Celestine V in 1294, whom Dante consigned to the outer reaches of Hell for his “great refusal”. Benedict deserves no such fate, although it was an extraordinary decision for a prelate and scholar deeply versed in Church history, aware of the challenges in maintaining unity in a worldwide Church; for a pope who in every other way was the champion and exponent of Catholic tradition.

It is unlikely that Benedict anticipated that Pope Francis would be his successor, or that he would live more years in retirement than as pope to see some of the consequences of his decision.

Like many Germans, he admired and understood the English-speaking world, supporting efforts for an accurate, non-ideological English translation of the Catechism of the Catholic Church, which he entrusted to Archbishop Eric d’Arcy, then Archbishop of Hobart; and of the third edition of the Missal of the Roman Rite.

He was a good friend to Australia with a disconcertingly broad knowledge of our situation. He visited us for the successful World Youth Day in Sydney in 2008, which attracted more overseas visitors than the Beijing Olympics in the same year, and, finally, against the prognostications of the experts, Pope Benedict blessed and opened Domus Australia, the Australian pilgrim centre in Rome in 2011.

Pope Benedict was a holy and prayerful priest; a Christian gentleman of the old school, who always remained a learned and reserved German professor. He was a good pope, not a great pope, but neither a failure. He preserved the Apostolic faith, taught regularly and magnificently, so that he is universally regarded as one of the finest theologians and writers in the papacy’s almost 2000-year history. He inspired many seminarians, who moved through to become zealous priests, and the numbers at his Wednesday audiences remained high. However, the hopes and bright expectations at his election were not all realised, and both his resignation and long years in retirement were surprises.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout