News not all bad for democracy in Southeast Asia

Democracy is taking a hammering in our backyard as old patterns return.

It’s been a tough few months for democracy champions in Southeast Asia and there is potentially more bad news on the horizon.

Thailand is in political crisis after a royalist/military nexus blocked the election-winning, reformist Move Forward Party from forming government, while Cambodian autocrat Hun Sen this week handed the country’s leadership to his son Hun Manet like it was the keys to the family car.

Myanmar’s violent military dictatorship has deferred what would have been sham elections in another sign of its imperviousness to regional and Western pressure to end the bloodshed against its own people and restore civilian rule.

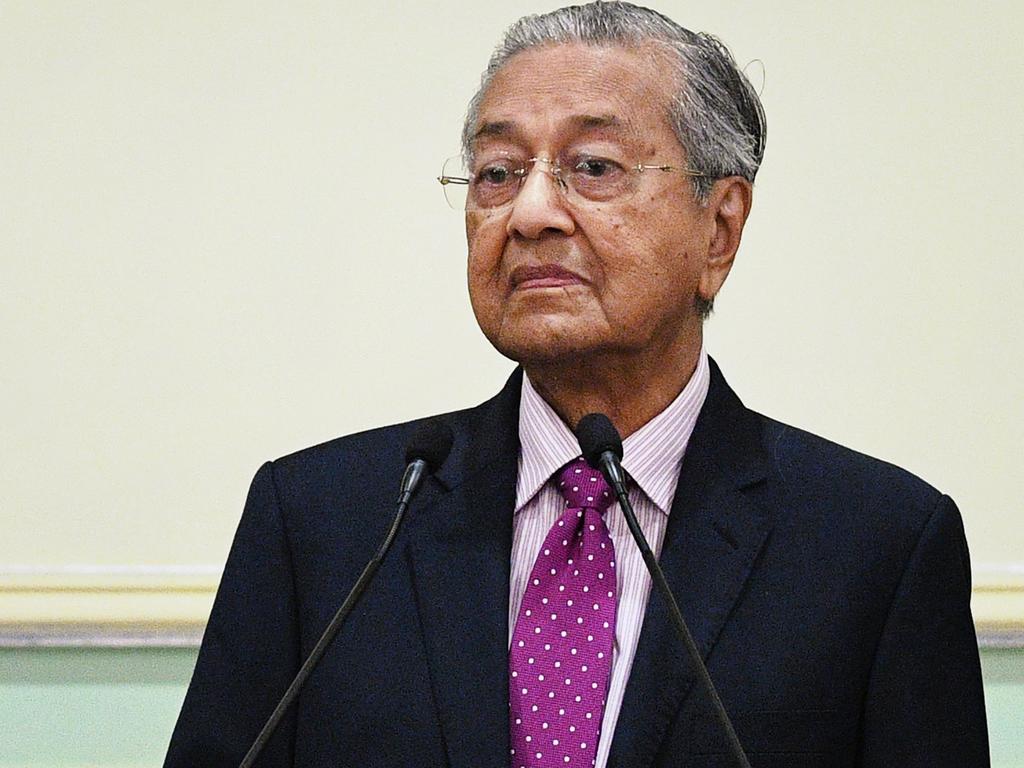

Malaysia faces a possible Islamic “green wave” in six state elections this weekend, a Super Saturday widely seen as a referendum on Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim’s fledgling government and a mirror of the rising religious conservatism there.

In Indonesia, where presidential elections will be held in February, the lead candidate is Prabowo Subianto, an ex-son-in-law of late dictator Suharto and former special forces commander accused of human rights abuses. He is the current defence minister.

From one week to the next, news of rising illiberalism – whether it’s Indonesia outlawing interfaith marriage, Malaysia banning pro-LGBT band 1975, or another state execution in Singapore – appears to underscore the trend throughout the states that make up the 11 Association of Southeast Asian Nations.

“There goes the neighbourhood,” one might suggest, given Vietnam and Laos are communist dictatorships, Singapore is essentially a one-party state and Brunei an absolute monarchy.

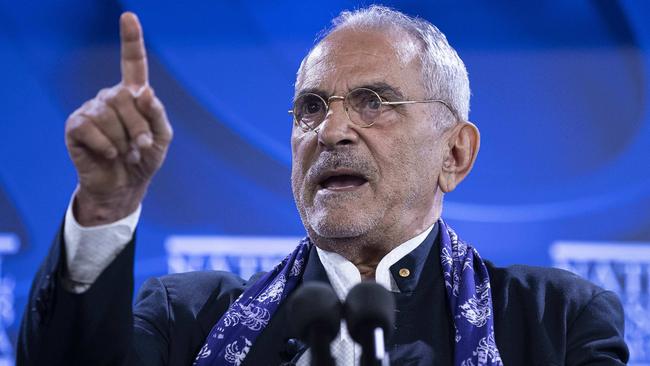

It comes to something when the Philippines – which recently voted in the son and namesake of the late, ousted kleptocrat Ferdinand Marcos as president – starts looking like a beacon on the hill, and tiny Timor Leste can lay claim to being a “twinkling light of democracy”, as its president, Jose Ramos Horta, described it this week at a Jakarta event to discuss the state of Southeast Asian democracy.

“We all remember what Southeast Asia was in the ’60s, and at least up to ’75 and beyond” – when dictatorships, civil conflicts and outright war tore at the fabric of the then Indo-China, and neighbouring nations turned against each other, the 73-year-old said.

ASEAN leaders were to be commended for decades of successful peace building in “this once very turbulent region”, and for unifying nations with vastly diverse cultures, economies and political systems, he noted.

“ASEAN set world records in economic growth and dramatic improvement in the lives of the people. With this came political openness and incremental advances in the rule of law and freedoms. We all know Southeast Asia – 40 years ago what it was, the extreme limitation of movement, of freedom – and what it is today.”

Yet democracies are fragile, and can be destroyed both from within and without, Ramos Horta told his audience.

“The world has seen them unravel at the hands of an autocrat or dictator more than once. We are seeing the signs in more than one region of the globe at the moment but autocrats and dictators could never destroy democracy alone.

“No dictator or autocrat has risen from a democracy without the support of the businesses and moneyed classes.”

It doesn’t take a genius to conclude Ramos Horta’s speech contained a warning for his own neighbourhood, where perennial concern over democratic backsliding has grown more acute amid intensifying US-China rivalry and a reassertion of traditional elites.

In that context, should Hun Manet’s hereditary succession in Cambodia, and the sabotage of Thailand’s election results by conservative royalists intent on keeping power at the expense of democratic institutions, be seen as a win for authoritarian China?

And what does this all mean for Australia, which must navigate a changing political climate in which the scales appear to be tipping in favour of Southeast Asian autocracies?

It’s tempting to blame Beijing for contributing to the democratic decline, given it hardly sets a shining example with its territorial aggression and divide-and-conquer regional diplomacy.

There’s an argument to be made that the US-China contest has given Southeast Asian leaders more licence to do what they want and get away with it.

But Southeast Asia does not have liberal democracies. Those that can still be counted as democracies at all – Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Timor Leste, maybe Singapore, if you squint – thrive on patronage. Powerbrokers and traditional family elites largely call the shots. Even Indonesia’s outsider, President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo, has built a political dynasty during his time in power.

Still, most long-term observers insist the current decline is not terminal and the trends reflect more of a mixed bag of good and bad news.

ANU professor Marcus Mietzner, an astute Indonesian political analyst, says Indonesia has fared better than most of its neighbours, even if “the fact its democratic decline was not as bad as others is hardly reason for enthusiastic celebration”.

“Nevertheless, democracy survived, which is more than one could say about Thailand or Myanmar.”

Earlier this week, the Jakarta Post newspaper warned the country’s journey from Suharto’s military dictatorship to democracy was about to come “full circle”, and Indonesians should prepare for the possibility their democracy could quickly be overturned.

“Anyone old enough to remember the heady summer of 1998 who sees the direction of the country’s politics today will feel we are still living under the shadow of Suharto. It is as if the strongman never left the building,” the editorial said.

It cited efforts to alter the constitution to allow Jokowi to seek a third term, restore a closed-electoral system in which party elites nominate MPs, and the military’s increasing presence in civilian life – including Prabowo’s run for the presidency.

Mietzner says the fact the campaign for a third Jokowi term and an election delay both failed demonstrates Indonesian democracy is surviving. “A Prabowo presidency in 2024 is a risk for democracy, but that risk is lower than in 2014,” he added, when he first ran for high office.

“If elected, he will be in his mid-70s in his first term, setting limits to his ability to develop a full authoritarian project.”

Regardless of who wins, “the inauguration of a new president would signal the stability of the existing low-quality democracy”, if not its robust health.

Malaysia’s elections this weekend present a more immediate challenge, both to the pro-democracy Anwar government and to the 30 per cent of the population that is not Malay Muslim.

A drubbing at the hands of the Malay/Islamist opposition could be the beginning of the end for Anwar’s uneasy coalition with the United Malays National Organisation – the party responsible for the $US4.5bn 1MDB misappropriation scandal, predicts Tasmania University Malaysian politics watcher James Chin.

Saturday’s polls in Selangor, Negeri Sembilan, Penang, Kedah and Islamist-held Kelantan and Terengganu “will confirm whether the green wave is real and whether young Malays have benefited from 30 years of affirmative action; whether they have accepted modernity, or want to go back to the old ways”, he says.

“Only a few years ago a lot of people thought things were moving in the right direction, but in maritime Southeast Asia especially, culture is stronger than democracy. Southeast Asians are very conservative, and what we are seeing is the reassertion of traditional elites.”

Lowy Institute research director Herve Lemahieu cautions against applying too general a lens to a region that has “never had a democratic heyday”, but which nonetheless boasts entrenched democracies in Indonesia and Malaysia.

Philippines democracy, too, has demonstrated robustness just by surviving former president Rodrigo Duterte and his failed lurch to China. His successor, Ferdinand Marcos junior, has been one of the region’s bigger surprises with his enthusiastic pivot back to the West.

Even within Cambodia, a popular view of the Western-educated Hun Manet’s leadership succession is that it presents a rare opportunity – after 38-years of increasingly repressive rule under his father – for gradual reform and a reset of relations with the West.

“Southeast Asia has always operated in a cycle, some years backsliding, others improving,” Lemahieu tells Inquirer.

“When it is improving we need to be mindful of the flaws we too often paper over, and when things deteriorate we have to be mindful there is still cross-regional support for the principle that countries ought to be democratic.”

Cambodia, now a capitalist dictatorship, continues to pay lip service to the concept of democracy through (rigged) elections, while even Myanmar’s odious coup master Min Aung Hlaing promises polls by 2024.

Why? “Because Southeast Asia’s autocrats still crave the idea of having electoral legitimacy,” says Lemahieu, who insists Australia has acclimatised to what the region is, and not what it might wish it to be.

“It’s almost the case that we have managed to carve out a Southeast Asia exceptionalism. Australia is far more pragmatic in its foreign policy in Southeast Asia than other Western players”, including the US whose decision to place treaty partner Thailand in deep freeze after the 2014 coup pushed it closer to China.

The region’s autocracy/democracy seesaw has conditioned Australian policy makers to be clear-sighted about what can be achieved there – in contrast to a dewy optimism over India – while still supporting democratic institutions, independent media and civil society, he says.

Australia has invested heavily in fortifying Indonesia’s democratic framework, with bureaucrats seconded into key ministries to help improve domestic governance, civil service and the education system.

Still, says Mietzner, a high-quality Indonesian democracy is probably less important to Australian policymakers than a reliable neighbour that remains open to strategic discussion on how to contain China.

“Even if an autocrat came to power in Indonesia, she or he would be unlikely to align the country firmly with China – which is what counts for most Western leaders.”

Likewise, ASEAN countries understand their best interests lie in fostering a diverse set of foreign relationships and not being beholden to one power such as China, even as they “see through US rhetoric on an alliance of democracies and realise the priority for Washington is simply to hang in there”, says Lemahieu.

The US is learning lessons from Australian engagement with the region, the most important being the need to turn up to meetings – such as next month’s ASEAN-led East Asia Summit in Jakarta.

Australia will certainly be there, performing its usual high-wire act of building regional influence while quietly raising concern over rights abuses.

It’s not an easy trick, and not everyone is a fan.

“Australia lives in the neighbourhood so must deal with the fact these leaders are there, but should also be mindful that might not always be so,” says Cambodian American political scientist Sophal Ear, who warns Canberra should take care its pragmatism doesn’t nudge it on to the wrong side of history.

“When the grandkids ask what position Australia took and where was it when this was happening in the neighbourhood, you want to be able to say you took a position to be proud of.”