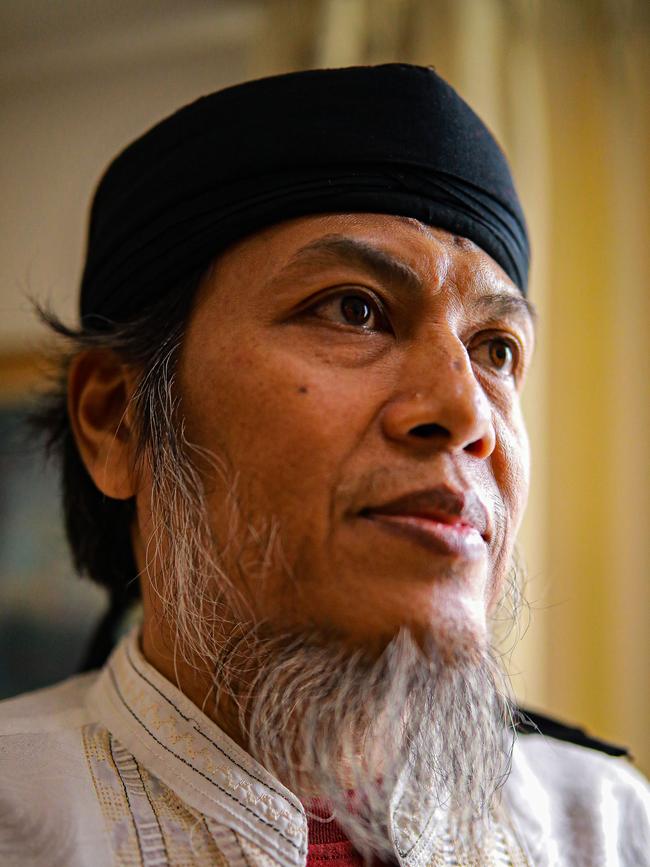

We have changed, says Indonesia’s Jemaah Islamiah leader Para Wijayanto

The leader of Indonesia’s Jemaah Islamiah says his terror outfit got it wrong, he is sorry and that he is dissolving the group.

For decades, Jemaah Islamiah wreaked terror, bloodshed and misery across Indonesia with its homegrown brand of Islamic extremism, murdering and maiming more than 1000 innocent people, including hundreds of Australians, in Bali and Jakarta.

Now the leader of Jemaah Islamiah says his terror outfit got it wrong, he is sorry and he is dissolving the group so its leaders can instead work towards “world peace”.

In an interview with The Australian held under the watchful eyes of counter-terrorism police from Indonesia’s elite Densus 88 force in a Jakarta hotel, Para Wijayanto has for the first time apologised to Australians and the Australian government for his group’s murderous attacks and vowed it will never happen again.

Southeast Asia’s most notorious terrorist group should have been promoting Islam through peace, not violence, he said.

Having failed so momentously to do that, it is being disbanded, never again to pose a threat to Indonesians or Australians.

And he has a special message for the Australian people who bore the brunt of its remorseless, barbaric brand of terrorism alongside millions of Indonesians: “Don’t worry – we have changed.”

“As the last amir of Al Jemaah Islamiah, I would like to offer a sincere and heartfelt apology for those incidents, where there were many casualties, both in terms of lives and property,” the 56-year-old said in an hour-long interview in which he sought to explain the group’s ideological shift from spreading terror to “spreading goodness”.

“JI should have been responsible for those events but the Indonesian government, with its kindness, handled everything, including providing compensation and restitution. Likewise, the Australian government, where some victims were treated.

“This was really our responsibility but we are very grateful for their actions. So we apologise and express our gratitude for all that has happened. Now we have changed, and our thinking has evolved to re-evaluate how we approached things back then.”

Para Wijayanto said he would like the chance to meet Australian victims of JI terrorism and apologise directly to them, and find a way to make restitution for the evil they had done: “It is human nature: one makes mistakes, evaluates, and then improves for the future. We have changed. We now understand the religious teachings concerning the proper relationship between Muslims and non-Muslims. In essence, we will strive to do good and act justly to the best of our ability.

“This has become a guiding principle for us, as previously our hatred led to unjust actions.”

For millions of Australians and Indonesians, hearing the leader of the region’s most notorious terrorist death squad explain how hundreds of people were murdered because of a misinterpretation of Islam’s holy Koran will be a bitter pill to swallow.

Still, if Wijayanto is to be believed, the world will undoubtedly be a better place for JI’s demise, even if Islamic State-linked militant groups still remain active in Indonesia and The Philippines.

Some 202 people were killed – 88 of them Australians – in the twin blasts that Jemaah Islamiah terrorists detonated outside two Kuta beach nightclubs in Bali on October 12, 2002. Another 209 people were injured in what is still the most devastating terror attack conducted on Indonesian soil.

It was hardly the first or last time JI’s cruel and bloodthirsty militants would sow terror for its own sake. The al-Qa’ida-linked group was also responsible for the Christmas Eve church bombings of 2000, the Australian embassy bomb attack in 2004, the second Bali blast in 2005 and suicide bomb strikes on Jakarta’s JW Marriott and Ritz Carlton hotels.

In countless smaller attacks across Indonesia and the region, its militants murdered and maimed, including in central Sulawesi where three schoolgirls were beheaded for no other reason than they were Christian.

By Wijayanto’s own admission, JI’s road to Damascus has not come quickly.

It has taken years of intensive discussions and study of Koranic verses and Islamic law among leaders to understand that justice and doing good should not be limited to fellow Muslims but extended to non-Muslims.

He claims to have been working to dismantle the group from the moment he was made its leader in 2008 because it was clear JI members could not find Islamic justification for their actions, let alone the horrific terror attacks that occurred elsewhere in the name of Islam.

He says his efforts were interrupted by his arrest in 2019, though from jail – where he is currently serving a seven-year sentence – he has co-operated extensively with authorities, even handing over lists of remaining JI operatives in Syria and The Philippines to Densus 88.

Wijayanto points to the fact no major JI attacks occurred after the bombings of the JW Marriott and Ritz Carlton hotels in Jakarta in 2009 as proof of his sincerity.

His military commander, Khairul “Bravo” Anam, also present at Monday’s interview, described his main role in recent years to The Australian as that of a “firefighter” trying to prevent JI members from launching rogue terror attacks.

And in what will sound cruelly familiar to counter-terrorism officials worldwide, he conceded it was harder to prevent terror attacks than to launch them.

“Controlling was more difficult because many wanted to execute operations. There were many volunteers,” he said.

As JI’s top leader, Wijayanto claims to have declined all financial support from al-Qa’ida and other global terrorist networks because of their demands the group continue launching attacks within Indonesia.

He insists the 100-plus JI militants he sent to Syria between 2013 and 2018 were dispatched to fight Islamic State, not to join them, and that under his leadership the group has moved away from violence towards a focus on developing its network of 42 Islamic boarding schools.

Those schools now submit their curriculum for review by Indonesia’s religious affairs ministry.

JI leaders announced their intention to disband Indonesia’s most notorious terror outfit on June 30 and have been travelling the country with Densus 88 counter-terrorism police in recent weeks to appeal to its 6000-plus militant membership and sympathisers to surrender all weapons and explosives and pledge loyalty to the state.

So far, more than 30 weapons have been surrendered along with large quantities of explosives.

Wijayanto estimates around 80 per cent of JI’s followers agree with its dissolution while the rest have adopted a “wait and see” mode.

Asked why anyone should trust that this really was the end of JI, he conceded the group was now in a “phase of building trust and transparency”.

“Of course, we need to build trust, and the seriousness of JI’s internal commitment to the dissolution will be closely observed,” he said.

Regional terror analyst and JI expert Sidney Jones said she believed the move was sincere and likely driven by a desire to protect JI’s biggest assets – its boarding schools and charity network – from being targeted by the government.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout