Empty end for Jacinda Ardern, ‘saint’ of left

Jacinda Ardern shocked her party and country when she revealed she was quitting, leaving New Zealand Labour to face a looming recession and a likely election defeat.

Jacinda Ardern shocked her party and the country when she announced on Thursday that she was to step down as Prime Minister after 5½ years, leaving New Zealand Labour to face a looming recession and a likely election defeat without her.

Ms Ardern’s long-time heir apparent – finance chief Grant Robertson – immediately ruled himself out of the race to succeed her, leaving Education Minister and former Covid-19 tsar Chris Hipkins the frontrunner for the leadership.

Declaring she did not have “enough left in the tank” and would be stepping down as Prime Minister by February 7 at the latest, she said: “My time has come.”

In one of her most telling comments on Thursday, Ms Ardern admitted she was no longer the best person to take Labour to an election and beyond.

“I am leaving because with such a privileged role, comes responsibility: the responsibility to know when you are the right person to lead, and also, when you are not,” she said.

“I know what this job takes, and I know that I no longer have enough in the tank to do it justice. It is that simple.”

Anthony Albanese praised Ms Ardern for her “empathy” and “strength”, posting a photograph of the pair embracing each other.

“Jacinda Ardern has shown the world how to lead with intellect and strength,” the Prime Minister wrote on Twitter.

“She has demonstrated that empathy and insight are powerful leadership qualities. Jacinda has been a fierce advocate for New Zealand, an inspiration to so many and a great friend to me.”

Although known internationally as “Saint” Jacinda, by early last year the sheen started to come off, when New Zealand’s drastic lockdown meant even Kiwis were banned from coming home. The tourist industry crashed and businesses around the country failed as the cost-of-living crisis grew – a potential disaster that the usually deft Prime Minister at first denied was even happening.

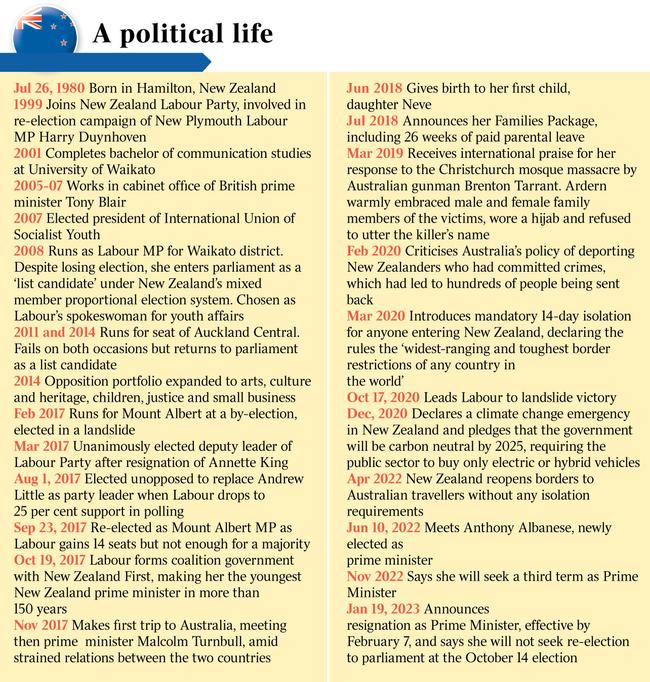

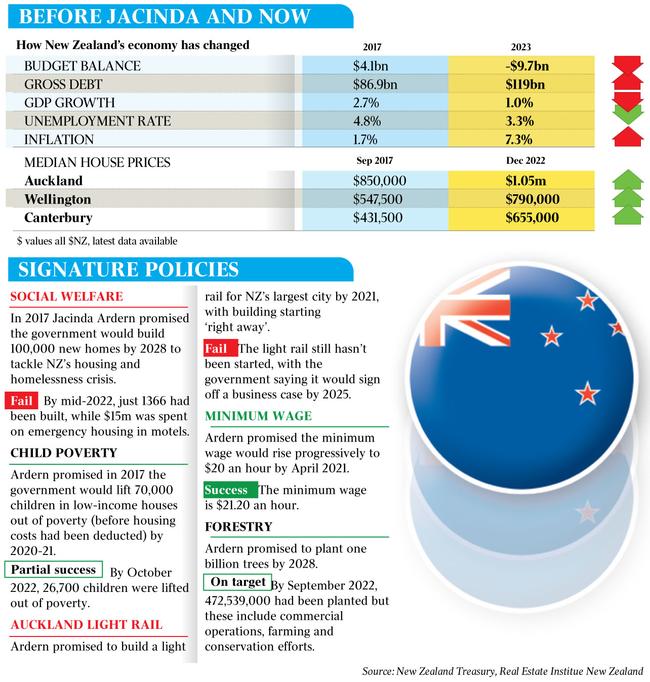

Meantime, Ms Ardern’s election promises, which helped secure her such an overwhelming majority in 2020, were turning to dust. Ms Ardern promised to build 100,000 affordable homes within 10 years; five years later, only 1366 had been built.

Emissions have increased by 2 per cent since 2018, net migration has turned negative for the first time in decades as young people flee the country for better opportunities abroad – mostly in Australia – and crime has seen an inexorable rise with a spike in violent gang activity. Like the rest of the world New Zealand is bracing for a recession this year.

By the end of 2022, rather than laughing and smiling her way through television interviews, Ms Ardern was beginning to look pale and haunted as media interrogators pinioned her on the government’s failures.

In the end, she decided the honourable thing to do would be to give up the reins to someone else.

Ms Ardern said she was “incredibly proud” of what she and her government had achieved in the last 5½ years, particularly lowering child poverty rates, increasing welfare support and increasing public housing stock.

“I have given my absolute all to being Prime Minister but it has also taken a lot out of me,” she said. “You cannot and should not do the job unless you have a full tank, plus a bit in reserve for those unplanned and unexpected challenges that inevitably come along.”

She went on to tell her fiance Clarke Gayford, who was sitting in the front row: “Let’s finally get married.”

Ms Ardern had kept her decision to a loyal handful, not even mentioning to her daughter Neve that she would be home a lot more in case the child talked. “Four year olds are chatty,” she explained.

While she had told her cabinet and caucus of her decision earlier on Thursday morning, not a hint of her decision had leaked; when

While she had told her cabinet and caucus of her decision earlier on Thursday morning, not a hint of her decision had leaked; when she stood to make two announcements at the Labour caucus in the North Island of Napier, she was expected at most to announce the election date and, possibly, a reshuffle.

While the timing was shocking, Ms Ardern’s decision to resign was not a complete surprise. Labour has been falling steadily in the polls throughout 2022. In the latest Kantar One News poll at the start of December, the rival National Party had widened its lead over Labour, rising to 38 per cent, while Labour fell to 33 per cent, its lowest since it came to power in 2017.

The country’s most popular leader ever had also seen her popularity crash to 29 per cent – her lowest since August 2017, just before she became Prime Minister.

In October, as the slide in the polls gathered speed, and even the usually tame New Zealand media began attacking her, rumours started to circulate that Ms Ardern wouldn’t make it to the general election. But most people expected her to continue, to fight through.

At the time, Michael Johnston, of the NZ Initiative think-tank, said her Christian faith – her parents are Mormons – meant she would feel bound by honour and ideology to keep leading her party through the fire of an election year.

Former Labor Party leader Bill Shorten also praised Ms Ardern as an “inspiration”. “Jacinda Ardern reimagined New Zealand and its place in the world. An inspiration to women and men everywhere, including those in my own life,” he wrote on Twitter.

Climate Change and Energy Minister Chris Bowen said MS Ardern “led her country through its hardest ever day”. “She inspired people around the world with calm, assured, progressive and robust leadership,” he tweeted.

Finance and Women Minister Katy Gallagher said: “You can’t be what you can’t see”. “I’m so glad that a generation of young women have been able to watch as Jacinda Ardern has led New Zealand with strength, empathy and grace,” Senator Gallagher said.

Independent MP Allegra Spender said Mr Ardern inspired many women including herself. “She has inspired many women to stand up and show that you can be a human, compassionate leader – certainly I was inspired,” she said.

The Labour caucus will vote on Ms Ardern’s replacement on Sunday. If no candidate receives two-thirds support within caucus, the leadership contest will go to the wider membership.

If a successor is chosen, Ms Ardern will step down, although she will remain MP for Mt Albert until April, to avoid a by-election.

Ms Ardern was the country’s first prime minister to achieve global fame. Her predecessors – Labour PM Helen Clark and the Nationals’ John Key – were widely recognised and admired but neither had the international allure that Ms Ardern enjoyed.

Almost from the time she came to power in 2017 aged just 37 she shone on the world stage. Despite her relative inexperience global leaders hung on her words, her empathy was, rightly, praised – especially after the Christchurch mosque attack in March 2019 when she wore a hijab while speaking with the families of the 51 victims and the wider Moslem community.

In December that year, she had to steer the country again through tragedy when Whakaari/White Island suddenly erupted, killing 22 people. Her empathy and kindness during both tragedies, turned her into an icon of the times, particularly in an era dominated by populists Donald Trump and Boris Johnson. Her tightening of the country’s gun laws after the Christchurch attack, and the “Christchurch call” – a commitment to eliminate terrorist and extremist content online, which she drew up with French President Emanuel Macron – solidified her reputation as an astute politician as well as a kind one.

New Zealand’s Opposition Leader Christopher Luxon said being prime minister of the country was a “tremendous privilege”.

“Very few people get the opportunity to do so and it’s important that when you do you make the most of that opportunity,” Mr Luxon said.

International respect for Ms Ardern grew early in the Covid pandemic, when she persuaded New Zealand into draconian restrictions, thus allowing the country to escape Covid almost completely for that first year, when the pandemic killed thousands around the world.

In the 2020 election, she was so popular that she was able to take the party to an overwhelming victory that gave Labour a single party majority – the first time this had happened since the start of mixed member proportional representation voting was introduced in 1996.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout