Ardern led from the heart, not head, to NZ’s great cost

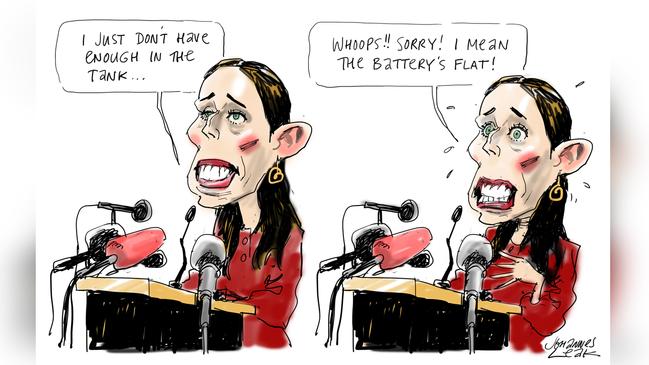

Unconventional to the end, Ms Ardern on Thursday unexpectedly quit as leader, claiming she had nothing left in the tank to give. Struggling in the polls, the Ardern government clearly had a fight on its hands for the October election despite winning in a landslide in 2020 at the height of uncertainty about Covid. Fast-forward to today and, like elsewhere, the cost of the Ardern government’s heavily interventionist pandemic response is starting to bite. The New Zealand economy is faced with soaring inflation and rising interest rates, prompting a cost-of-living crisis Ms Ardern’s opponents say is worse than a recession.

Announcing her departure, Ms Ardern said there was no secret scandal behind her resignation. Rather, it was about knowing when it was time to go. It reflects the fact that in New Zealand, Ms Ardern’s government has been tarred with failure and scandal. Ms Ardern’s inability to deliver what was her government’s first-term signature policy of 100,000 new dwellings to ease a housing crisis is emblematic of how economic reality can make a mockery of good intentions. With only a handful of homes built and the scheme rules making it suitable only for the wealthy rather than the needy, it was scrapped. Instead, more than $1.2bn has been spent placing families in motels and emergency housing where many have been exposed to sexual assault and crime. The three waters scandal, involving underhanded manoeuvrings in parliament to cement the government’s anti-privatisation agenda in water legislation, was a sign of an arrogant government running out of hand.

While progressives will celebrate the fact Ms Ardern was the second only world leader to give birth in office, her enduring legacy will be the extent to which she worked to unpick the economic reforms introduced by New Zealand finance minister Roger Douglas that delivered four decades of economic security. In response to a crisis in 1984, Douglas modernised the New Zealand economy by devaluing then floating the New Zealand dollar, removing foreign exchange controls, liberating the banking system, increasing electricity charges, introducing a fringe benefits tax on employers, slashing agricultural subsidies, and starting to phase out export incentives for manufacturers.

But as Oliver Hartwich, executive director of The New Zealand Initiative, writes in The Australian, under Ms Ardern, the basic pillars of New Zealand’s post-1984 settlement have been demolished. State spending has been increased despite Treasury warnings it was not sustainable. The Reserve Bank charter has been changed away from an inflation target towards employment targets and house prices. Trade unions have been rewarded with new Fair Pay Agreement laws that have made a once highly flexible labour market more rigid. A European-style unemployment insurance scheme will add to business costs and reduce incentives for the unemployed to find work. The reforms in welfare reflect a move to greater state control across the full gamut of policy areas.

There are lessons in New Zealand’s Ardern experiment for Australia and Anthony Albanese, who has pledged to lead in the tradition of Bob Hawke who, with Paul Keating, introduced to Australia many of the reforms Ms Ardern has sought to erase in New Zealand. Like Ms Ardern, Mr Albanese has moved to a more centralised wages and industrial relations posture that rewards the trade union movement. Jim Chalmers has called for a review of the Reserve Bank that could result in changes to how it decides issues including interest rates, as happened in New Zealand under Ms Ardern. The Treasurer has also adopted the New Zealand budget model of introducing a range of non-financial benchmarks into the budget process as a way to measure community wellbeing.

Mr Albanese praised Ms Ardern following her resignation and said she had been “an inspiration to so many”. He said Ms Ardern had shown the world how to lead with intellect and strength, and demonstrated that empathy and insight are powerful leadership qualities. In the end, Ms Ardern showed enough self-awareness to be able to leave the job at the time of her choosing, a rare achievement in politics. In doing so she has been able to preserve the public image she most wanted to protect. But her financial legacy will continue to be felt in New Zealand for many years to come.

New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern was a consummate left-wing leader for her time who wants to be remembered for kindness. She was lauded internationally for displays of conspicuous compassion in the face of a crisis. But at home in New Zealand, against the international image that reached its zenith when she appeared on the cover of Time magazine in March 2020, Ms Ardern’s record and political reputation were not so good. Above all, Ms Ardern, a former president of the International Union of Socialist Youth, was a poster child for the perils of leading from the heart and nourishing an already bloated, bureaucratic welfare state, the consequences of which will reverberate through the New Zealand economy long after she has gone.