Israeli troops have amassed at the northern border ahead of an expected conflict with Lebanon and Syria

While rockets have been showering on Israelis from Gaza, the much greater threat forcing everyone to stockpile food for their bomb shelters is coming from Hezbollah, in the north of the country.

As Israeli tanks begin shelling Hamas positions before a ground offensive into Gaza, it’s not the homemade rockets fired from the south prompting residents to stockpile food for their bomb shelters; it’s guided missiles and battalions of militiamen preparing a second front along Israel’s northern border.

Backed by Iran and equipped with formidable weaponry, the outspoken fear among many Israelis is the likelihood of a regional conflict with Hezbollah in southern Lebanon and allied forces in Syria, especially for those living in the Golan Heights, a territory of mountainous hills seized from the Syrians in 1967.

A full-blown incursion into Gaza stands to trigger these forces into a response, with aircraft fire and drone warfare already under way.

It’s why the Israel Defence Force has spent weeks fortifying its northern barriers, deploying tank columns and infantry to towns near Lebanon and carrying out bombing raids on airports in Damascus and Aleppo to destroy the runways.

The US has joined these efforts, according to US Defence Secretary Lloyd Austin, who said the American military had struck two Syrian facilities suspected of being used by Iran, an action that followed recent threats to US troops in Iraq and Syria, causing mild injuries to almost two dozen service personnel.

Israelis have been advised to stock their safe rooms with three days of water and foodstuffs in preparation for any northern attack.

Twenty-eight towns near the border with Lebanon have already been evacuated, with residents either moving in with family or accepting government-funded accommodation in the safer centres of the country.

But even with so much of the northern populace on the move, it’s possible to find holdouts and stragglers. Reaching them is another matter, with navigation in this region somewhat challenged by the scrambling of GPS signals, a tactic intended to interfere with missile launches from Lebanon and elsewhere, which rely on the same systems.

In a similar vein, traffic blockages are also no longer appearing on Google Maps or Waze throughout the country; this is to prevent terrorists from establishing locations of civilian concentration.

In Majdal Shams, a Druze village mere kilometres from the Israeli border with Syria, the prevailing belief is that Hezbollah may be less likely to aim its missiles here because the town was once a Syrian enclave. Plus, its residents are not Jewish.

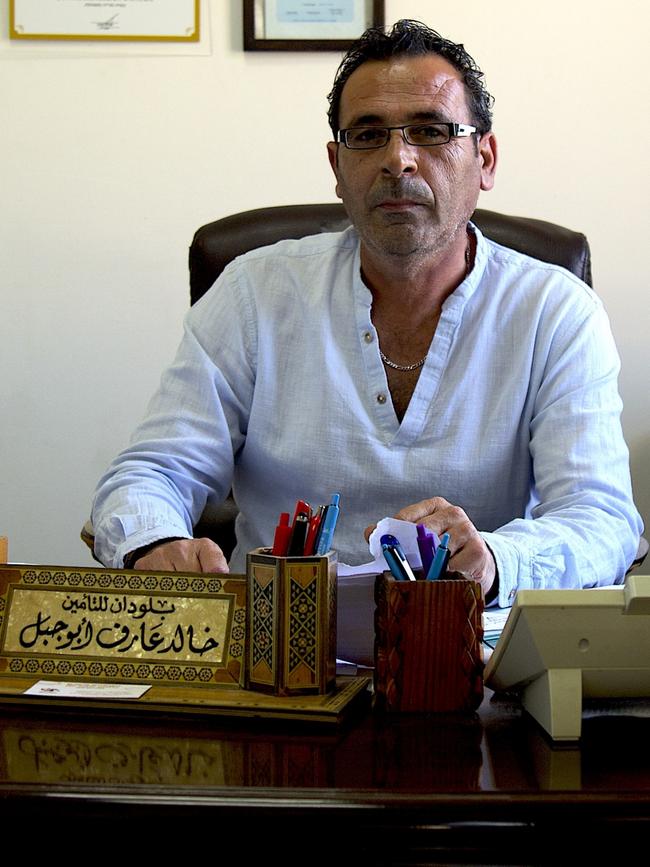

Khaled Abu Jabal, an insurance broker, explained that only people of the Druze faith could buy a home in Majdal Shams. Druze adherents living beyond the immediate municipality were permitted to rent, unless they married a local, an option generally unavailable to anyone born outside the faith.

Considering his own safety, Mr Abu Jabal said moving to Tel Aviv or staying in Majdal Shams made little difference, given that both cities face the threat of rocket fire. To leave town, he said, also ran counter to his philosophical view of the world.

“The Druze have one belief,” Mr Abu Jabal said. “When it’s your time to die, it’s time to die. Whether there’s a war here or in Australia – if God says I’ll die in a war, I’ll die in a war.”

Not that he’s living without fear of the impending conflict, or its economic consequences.

“We live in fear of rockets, from militias in Syria. We’re living under the threat of war,” he said.

Residents who would ordinarily work in nearby farming villages were unable to do so, he added, owing to a lack of bomb shelters to protect them.

Travel west to the town of Kiryat Shmona, closer to the Lebanese border, and the IDF presence here becomes rapidly apparent. Roads have been ravaged by the movements of tanks, causing motorists to hear an odd vibrating sound as they cruise the highways, similar to that of a flat tyre.

Kiryat Shmona, with a population normally around 22,000, has seen an exodus of people since the October 7 massacres and the sporadic, almost daily exchange of fire with Hezbollah forces that followed. These are clashes that involve antitank fire on Israeli towns or military posts, followed by IDF airstrikes.

With storefronts closed and its streets deserted, The Australian found a small group of men who’d gathered to play cards and sink beers in a neighbourhood community centre, their plan being to move closer to Tel Aviv once the weekend arrives. Not out of fear, they said, but out of the “loneliness and tension” they were sensing.

“Hezbollah is a monster,” said Gigi Yoram, a long-term resident of Kiryat Shmona who said regardless of what happened in the south the army needed to enter Lebanon and rout Hezbollah in the north.

Asked how he’d feel if that didn’t happen, Mr Yoram shook his head and insisted such a scenario wasn’t conceivable. “That can’t happen, it will be a complete fadicha,” he said, using an Arabic word to describe a snafu of great embarrassment.

The last war between Israel and Hezbollah, in 2006, resulting in about 1500 deaths, many of them on the Lebanese side of the conflict. “If they won’t take care of them now, we’ll always live in fear,” Mr Yoram said. “Since 2006 until now we live this reality.”

Further south, closer to the Sea of Galilee, most communities have beefed up security and begun training first-responder groups for any ground forces that enter these territories from Syria or Lebanon, the idea being to hold off an attack until the IDF arrives.

Asked why he was staying to fight, a citrus farmer who asked not to be identified said at a certain point of danger he would send his wife and children away to safety.

“I’ll defend (the community) better with them not here,” he said. “Until then, this is our home. I can’t leave the place. I wouldn’t feel good with myself.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout