Families of Israeli hostages cling to last traces as proof of life

As news of a deal to release those taken on October 7 takes shape, three family members speak about the anguish of limbo over the past six weeks.

Anat Shoshany clings to the last words sent by her grandmother, Adina Moshe, on the morning of October 7. As terrorists ransacked the 75-year-old woman’s home in Kibbutz Nir Oz, Ms Shoshany knew a tragic outcome was near and wrote a final goodbye to the woman who helped raise her.

“And she answered: ‘Sweetie, I love you a lot’,” with a heart emoji. Not long after, Ms Moshe’s husband was murdered before her eyes and she was dragged outside and kidnapped to Gaza on a motorbike, her abduction filmed and uploaded online.

It’s the only proof Ms Shoshany has seen that she’s alive.

Hen Avigdori received a final message from his wife Sharon, 52, and daughter Noam, 12, as sirens blared across Kibbutz Be’eri. Sharon assured him they were en route to a safe room, as did her brother, Avshalom, whose body would later be found by soldiers. There’s no visual evidence that either Sharon or Noam are still alive, but authorities have said with confidence that both were kidnapped, a conclusion drawn after weeks of unimaginable grief.

“It was two weeks of, I call it, the hell of unknowing,” Mr Avigdori said. “I cannot even describe it.”

Chen Mahlof last spoke to her father, Michel Nisenbaum, at 6:57am as he drove through the southern city of Sderot under rocket fire. He was supposed to pick up Ms Mahlof’s niece but suddenly stopped answering the phone, with repeated calls only yielding his voicemail. Eventually, Ms Mahlof heard a strange voice come over the line.

“The terrorists answered my phone call,” she said. There was shouting in Arabic, the word “Hamas”, and many others she didn’t understand. Then the call went dead. “From that point we have nothing.”

These are a sampling of cases epitomising the agony of some 240 families caught up in the hostage crisis unfolding between Israel and terror group Hamas. For six weeks they’ve rallied for a deal to release those in captivity, marching from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem and beseeching congressmen in Washington. They’ve held weekly street protests with thousands of impassioned Israelis armed with snare drums, whistles and megaphones.

With an agreement tentatively reached and the first movement of hostages looking imminent, the dilemma for many families is waiting to find out if their loved ones will be released in the initial batch of captives, scheduled to walk free as early as Thursday.

This fragile compact could also stand as their last hope of being reunited, with time no longer on anyone’s side, as it was during the initial phases of the war. In the weeks after October 7 the world was given a slow trickle of releases, starting with American citizens Judith and Natalie Ra’anan, followed by the freeing of two elderly hostages, Yocheved Lifshitz, 85, and Nurit Cooper, 79, one week later.

Israeli special forces surprised everyone with a subsequent announcement that they had rescued 19-year-old Private Ori Megidish from a house in Gaza, a thrilling moment for the country that briefly revived memories of daring and ingenious hostage rescues the IDF once prided itself upon.

But since the release of Private Megidish, the families of those held captive have received only grim news. Last week, the IDF recovered the remains of Judith Weiss, 64, not far from Gaza’s Al Shifa hospital. Hours later the IDF said the body of another abductee, Corporal Noa Marciano, 19, had been returned to her family for burial.

The hostages are almost certainly being held underground, in a honeycomb of tunnels protecting the Hamas leadership from aerial bombardment. An overriding fear is that the longer they’re held in place, the greater their chance of being injured in an airstrike, or succumbing to some other fate.

“My great hope is that they are together, and I have another hope that they are together with other kids,” said Mr Avigdori of his wife, Sharon, a special needs teacher, and daughter Noam. “We heard a rumour – it’s not confirmed – that there are some kids there who is autistic, and I really, really hope they’re in the same room with my wife, because if there’s anyone who can help an autistic kid in this situation, it’s my wife.”

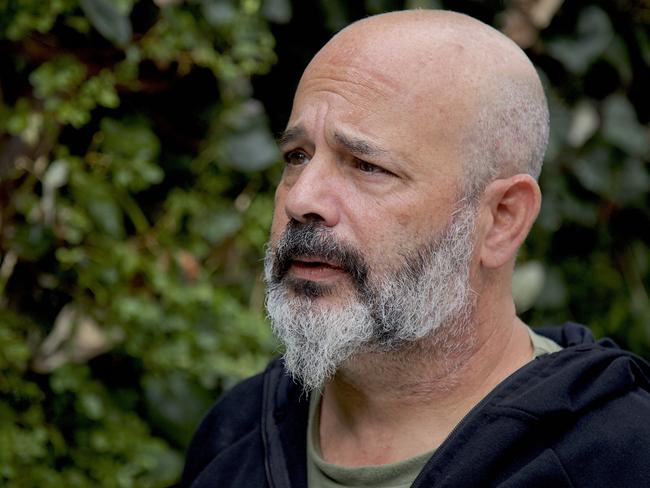

Mr Avigdori is a prominent voice among the sea of families trapped in this wretched dilemma. He’s also a comedy writer by trade, a factor he says has kept him well-equipped to manage the emotional hell of the past six weeks. One rule he follows is to severely limit his consumption of news and social media; he’s insistent about avoiding exposure to false hope.

“We talk about the sarcasm shield that I have – not everybody has it,” he said. “There are people that life didn’t prepare them to this kind of thing. Life didn’t prepare any of us, but I came with a baggage that helped me. This shield of humour and cynicism, it’s helped me on a daily basis. It’s helped me to deal with my emotions. It helped me to stay focused.”

Mr Avigdori and his 16-year-old son, Omer, stayed in the centre of the country on the weekend of October 7 while Sharon and Noam travelled to Kibbutz Be’eri for a visit with family. That fateful decision has paired the men of this family on a journey of angst that few could truly conceptualise. To survive, they came to an agreement.

“We make a deal in the first day that we stay strong together, and the deal was with two terms: I won’t hide any information from him, and he won’t hide any emotion from me. And this was working out fine, but I don’t have any information to give him,” Mr Avigdori said.

They debriefed every night on the balcony of their apartment in Hod HaSharon, where Omer would share tidbits about school, or girls, and Mr Avigdori gave back whatever he could. “And when he asked me, ‘Can they be dead?’ I say, ‘Yeah, they can be dead’. And it was two weeks of … I don’t wish anyone to have this kind of two weeks. I cannot even describe it.”

A breakthrough came when soldiers told them with “the highest level of certainty” that Sharon and Noam were being held captive, a finding seemingly based on intelligence gathered from the territory. It was a moment of head-rushing relief, but weeks have passed and they’ve heard nothing since. “We don’t have any pictures, any videos, any recording – nothing. We haven’t heard any new information.”

In the assortment of families thrown together by the October 7 attacks, there are circles of people who already share a bond. There are the kibbutz families who lived in the same communities and survived the attacks, each now bearing the scars of their own stories, or the trauma of knowing people who were murdered.

Further afield are the relatives of people taken hostage from the Nova dance music festival, who’ve formed their own support network among the wider collective. And then there are people like Mr Avigdori, who’s found himself drawn into this crisis purely by chance, because his wife happened to be visiting a kibbutz when the massacres took place.

Uniting these disparate families of varying geographies and political persuasions behind a singular voice has proven almost impossible. Many hold divergent opinions on whether to cut a deal with Hamas, or whether to engage in political activism. Some have flown to Athens for diplomatic meetings. Some have given speeches to large crowds or routinely appear on television. Many are simply unable to speak at all, such is their despair.

Ms Machlof, a 33-year-old woman living in Ashkelon, is in one of the most unenviable and loneliest positions of all owing to the status of her father, Michel Nisenbaum, whose car was found burned out and abandoned outside the city of Sderot. Officially, he’s listed as a kidnapping victim, but Ms Machlof is doubtful of the military’s evidence.

Without reliable proof that he’s being held hostage, Ms Machlof said she finds it difficult to relate to the broader group of families who know for sure that their relatives are being held in Gaza. Some of these families congregate in a mid-rise office block in central Tel Aviv, about one hour’s drive from Ashkelon, where three floors have been donated for their lobbying and advocacy work.

“Everything’s happening in Tel Aviv and I’m here, so it’s difficult,” Ms Machlof said. “A lot of families have the certainty that I don’t and I find it very difficult to connect. What the (hostage representative group) is doing is amazing, it’s just very difficult for me to connect with them because I’m not there, I’m not a kidnapped family.”

Several weeks after her father went missing, Ms Mahlof was given a document by the military saying her father was “probably kidnapped”, an assumption based solely on the location of his iPad, which had been tracked to the Gaza Strip. It’s a line of reasoning that proved too flimsy to provide any comfort; even the words “probably kidnapped” felt insulting.

“Everything they could steal, they stole,” Ms Machlof said, referring to the terrorists and Gazans who flooded the border and made off with clothing and appliances. “They stole kids toys, they stole (water filters). Who says they didn’t steal the tablet? (My father) is not bound to the iPad with a chain.”

The IDF is known to be using three categories of classification to organise suspected hostages – those with one kidnapping indication, two kidnapping indications, and those known without doubt to have been kidnapped. Ms Mahlof’s father is in the first category, on account of the missing iPad; Mr Avigdori’s family is in the third category, on account of the military’s intelligence.

Whatever trust Ms Mahlof still held in the IDF after October 7 eroded further that day she was delivered the news. She said it felt like the IDF was finding ways to hurry up and close her father’s missing persons file. In doing so, they placed her family in a terrible state of limbo, one where her father is neither confirmed as missing, as dead, or as kidnapped.

“It feels like they’re coming (and telling you) to get rid of you,” she said.

Serving in the military is foundational to Israeli life, forming an unspoken contract between the people and the state. At the age of 18, young men and women forgo career-building and travel to sacrifice up to three years in the army, agreeing to serve roughly one month each year as reservists until they reach their 40s. It’s been this way since the founding of Israel in 1948, and in exchange for this commitment, the state is supposed to ensure the safety of its civilians at all times.

Aside from the reputational damage caused, the stunning failures of October 7 have to some extent shattered the trust and faith that Israelis once put in their venerated army, leaving many in a state of disillusionment about their security. Residents evacuated from the south are wondering if they’ll ever move back. Meanwhile, a question mark still hangs over the north of the country – that is, can residents of Kiryat Shmona, or Snir, or Metula, really move back to their homes near the Lebanese border while Hezbollah, which harbours the same murderous intent of Hamas in Gaza, idles so closely nearby?

“The first responsibility of the leaders here is to bring (back) people alive,” said Ms Shoshany, an accountant living in Tel Aviv, whose grandmother, Ms Moshe, is being held hostage. “Their first commitment is to civilians, otherwise what are we doing here? Why do I pay taxes, and why do I live here? And why did my grandparents live here?”

As Ms Shoshany tells it, her grandparents were the “main characters” in her life growing up in the south. She spoke of months living with them in the tiny village of Nir Oz, near Gaza, a lush, storybook farming community where kids roamed barefoot and people depended on each other through mutual assistance and cooperative living.

Theirs was a love affair for the ages. When Ms Shoshany’s family walked through the wreckage of Nir Oz and discovered Ms Moshe’s mobile phone, they saw for the first time the romantic notes that she and her husband, David, had been sending to each other, even after 53 years of marriage.

“They were in love like they just met – it was unbelievable,” Ms Shoshany said. “When we found her phone after everything, every single morning he would text her, “Good morning my beautiful wife, I love you – another day with you, how lucky am I?”

Atrocities committed at Nir Oz challenge the depths of human imagination. Ms Shoshany said her grandparents reported hearing their elderly neighbour, Bracha Levinson, being shot by Hamas terrorists, who then used Ms Levinson’s phone to upload footage of her body to her Facebook account, where young family members encountered it.

The Moshes had been sheltering in their safe room when terrorists tore their way inside, murdering David in front of Adina and dragging her through a window, then onto a motorbike destined for Gaza. In the wave of emotions that followed, some in Ms Shoshany’s family were even furious that she was taken alive.

“You know the first week, we were angry. Why didn’t you kill her? Why didn’t you murder her with him? Why she needed to experience this horrible, horrible experience, to see with her own eyes her husband, her beloved husband murdered in front of her?” she said.

Their desire for a hostage deal has been evident since day one, her family even going so far as to purchase Ms Moshe’s favourite soaps and pyjamas to be ready for the moment her captivity ends.

But even a deal as advanced as the one slated to start as early as today can’t guarantee the release of Ms Moshe or the other hostages, and even Ms Shoshany conceded that it hasn’t been easy watching certain captives walk free while her grandmother has been left behind.

“You can’t stop your jealousy,” she said. “The first reaction is, like, why not me? Why is it not her? But one moment later you’re like, okay, they’ve survived for two weeks. They were taken alive and brought back alive, maybe less healthy. I’m sure their mental health is not so well, but they did it, it’s possible.”

Another point, raised by Mr Avigdori, seems to have fallen by the wayside in all the discussion: that once the hostages return home – and he’s sure they will – a longer-term battle for their recovery will begin.

“They will come back as other people,” he said, “and we have to save our strength to deal with it, to rehabilitate them, their soul and their mind. It’s going to be a long process. If we break now, they’ll have nobody to lean on when they come back, and this is the most important mission of our lives since.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout