But actually that shimmering surface similarity was entirely misleading.

This is a chastened and mature Australian leadership, which has absorbed all the sobering lessons of the 10 years of Xi Jinping’s rule in China.

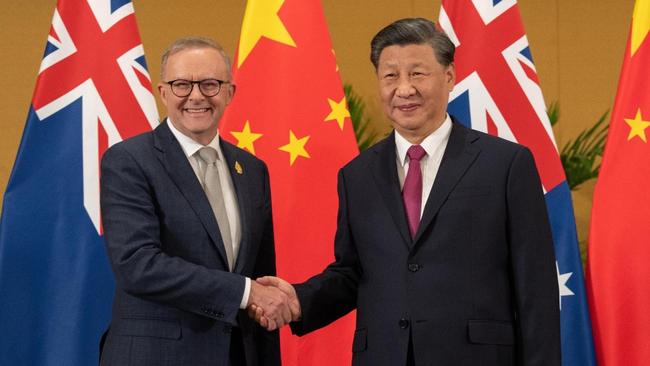

Anthony Albanese’s formal comments at the start of the first bilateral heads of government meeting in six years, contained these critical words: “We have had our differences and we won’t resile from our interests and our values.”

Reasonably enough, Albanese expressed a willingness to work together, a desire for better relations and a general expression of goodwill. But he also cited a determination to build a region based on international law and the provisions of the UN Charter. That’s a pretty direct reference to Beijing’s illegal occupation of islands in the South China Sea.

He also talked about Australia suffering “supply chain shocks”. That’s also mostly down to China.

This summit moment, though historic in its way, is still subject to difficult interpretation.

Beijing decided some years ago to punish Australia for various sins and crimes – banning Huawei from our 5G network, strong legislation against foreign interference in our politics, walking away from an extradition treaty, banning Chinese investment in our critical infrastructure, human rights criticisms, calling for an international investigation into the causes of Covid, etc.

It was always the case that Beijing would punish us to make us change our policies, and if we didn’t change our policies then it would finally decide that continuing the punishment no longer served its interests. It would then rehabilitate us. This has been Beijing’s pattern with numerous other nations, notably Japan. Also, Beijing would like us to withdraw our opposition to its joining the Trans Pacific Partnership.

It’s also the case that, with striking predictability, the Australian relationship with China tends to mirror the US relationship with China. Traditionally, the Australian desk in the Chinese Foreign Ministry sat in the Americas section.

It’s surely no coincidence that when Xi decides to meet US President Joe Biden, and take a number of actions the Americans would be happy with, such as condemning any use of nuclear weapons in Ukraine, resuming climate change co-operation talks, welcoming US Secretary of State Antony Blinken to visit Beijing, that it also decides to have a little thaw with Australia.

A few months ago, senior Chinese diplomats in Canberra were demanding that Australia take “concrete actions” to repair the relationship. We didn’t take any such actions. Indeed, it’s Beijing that should lift its trade embargoes on Australia, and free two Australian citizens, Cheng Lei and Yang Hengjun, who are imprisoned in China for no legitimate reason, but as a form of hostage diplomacy.

That this has not happened shows how hollow Xi’s words before the meeting really were, when he said that the Australia-China relationship “deserves to be cherished”.

After the meeting with Xi, Albanese declared: “We will co-operate where we can, disagree where we must and engage in our national interest.”

That’s the right formula, in good times and bad.

It was like old times in the China-Australia relationship – invoking again the talismanic, if massively overrated, moment 50 years ago when Gough Whitlam established diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China – as the two national leaders sat across a vast table and promised to be good, good friends.