Why did Allison Baden-Clay’s murder case grip the nation?

THE courtroom overflowed as strangers jostled with family for seats. Why did the trial of Allison Baden-Clay’s killer grip the nation?

IN her mind she’s making whirlpools in a backyard swimming pool with her cousin Allison Baden-Clay. They’re kids again. Allison’s laughter echoes across a suburban working-class home, a red-haired sprite raised by her mum and dad to be kind above all else, to love truly. Then they’re in Allison’s bedroom, inside a cubby house nook above her wardrobe. They’re playing with dolls and teddy bears, pretending to be mums and dads, pretending to be adults who live for nothing else but their children.

Then the voice of the forensic entomologist snaps Jodie Dann back to a reality nobody wants to be in, courtroom 11 of the Brisbane Supreme Court. And guilt snaps back with it. Jodie has spent 10 years working inside courtrooms like this one as a domestic violence court advocate with the Ipswich Women’s Centre Against Domestic Violence, west of Brisbane. She has dedicated her life to saving women from life-threatening encounters with men. “It’s like the world has said to me, ‘Jodie, this is your job’,” she says. “And you mustn’t be doing it very well because your own cousin is dead. How could I let my own cousin die like this?”

Day nine of the trial of Gerard Baden-Clay, the 43-year-old former real estate agent from the affluent western Brisbane postcode of Brookfield accused of murdering his wife Allison, 43, the mother of his three girls, on April 19, 2012. Today the forensic entomologist details the fly larvae evidence found on Allison’s body. The size of the larvae might determine how long her body lay on a muddy bank by the Kholo Creek Bridge in Anstead, western Brisbane.

Jodie fantasises, on occasion, on the ways in which Allison left her home and disappeared that night of April 19. She’s settled lately on a preferred scenario of her cousin scratching her husband’s face and screaming “F..k off” as she marches out of the house, slamming the door triumphantly behind her. But she knows it didn’t happen like that.

A woman in the back row of the public gallery whispers to a friend: “If you could sell these seats, how much would you sell them for?” The friend giggles. “I wouldn’t,” she says, nestling giddily into her seat. Any moment she might pull a box of popcorn from her handbag. Directly in front of them sit Allison’s aunt and uncle, Noel and Mary Dann, Jodie’s parents. Mary hears the women behind her chuckling. She shudders, prays for this macabre theatre to make a hurried end. “We have lived with this for two years,” Mary says. “These people turn up at the end but they couldn’t imagine what this family has been through.”

Jodie has been the go-to person for the family during the trial, marshalling them through testimonies, saving and organising seats for relatives, being an ear for Allison’s parents, Geoff and Priscilla Dickie, from whose side she rarely strays. “We would have preferred anything to this,” Jodie says. “If it turned out to be the Boogeyman we would have preferred that. Then the girls wouldn’t lose their father. We desperately wanted it to be the Boogeyman because that would have been the best-case scenario for those girls. But that wasn’t to be.”

Each morning from 10am, lines of up to 50 people have been waiting outside courtroom 11 to witness the final chapter in the disappearance of Allison Baden-Clay. A court staffer has been turning people away like a nightclub doorman, ushering others inside in shuffling groups of five and six. Those turned away rush upstairs to a second public gallery, an “overflow room”, streaming the hearing via a video link.

“There was hooting up there the other day when [Allison’s mum] Priscilla gave her testimony,” says Jodie’s daughter, Ashley, 21, who had been a flower girl at Allison and Gerard’s wedding. “Actual hooting.” Another Dann family member asked a random gallery punter if they could possibly go to the overflow room to make way for one of Allison’s elderly kin to take a seat in courtroom 11. “But it’s a better atmosphere in this room,” the punter said.

This room is where Priscilla and Geoff have sat stony-faced and resilient, absorbing with clenched fists and closed eyes every blow from the cases of defence and prosecution. They’ve endured photos of their daughter’s lifeless body, which was discovered on a creek bank 13km from her Brookfield home, 10 days after Gerard reported her missing. They’ve endured sordid details of the four-year affair Gerard had with a real estate colleague, Toni McHugh; the emails he sent her under the risible pseudonym Bruce Overland, the same name he used to trawl for sex on dating sites. “I have given you a commitment and I intend to stick to it — I will be separated by July 1,” he wrote to McHugh. “In the meantime, it doesn’t seem to be helping either of us to be snatching brief moments. I love you.”

On April 11, eight days before Allison’s disappearance, he wrote to McHugh: “This is agony for me too … I love you GG [Gorgeous Girl]. Leave things to me now.”

McHugh took the stand. “He was very adamant he didn’t have a relationship with his wife, that he didn’t love his wife, but at the same time he was never, ever disrespectful, callous, spiteful, hurtful,” she said through tears. “[He told me] he wasn’t ready to leave his wife but he was going to leave his wife. [He told me] that he loved me and one day he did want to come to me unconditionally.”

Priscilla and Geoff Dickie have heard Crown prosecutor Todd Fuller tell the court that both wife and lover had been due to attend the same real estate conference on April 20, the day after Allison disappeared. They’ve heard Fuller tell the court that McHugh insisted Gerard tell his wife that night that he would be leaving her. They’ve heard Fuller give details of their daughter’s blood and hair found in the rear of the family’s Holden Captiva, the car they were forced to downsize to from a $77,000 Lexus in the face of mounting debt. They’ve heard Fuller describe the deep scratches on Gerard’s face after April 19.

“The Crown says something happened at their Brookfield home,” Fuller told the jury. “The blood in the car tells us the car was used to transport her … to Kholo Creek. And finally, the scratches to his face, ladies and gentlemen, show us an injury consistent with fingers. Allison Baden-Clay’s mark upon him.”

Priscilla and Geoff have endured videos of Allison and Gerard’s two eldest daughters, then aged 10 and eight, being interviewed by two detectives from the Queensland Police Child Protection & Investigation Unit on the day their mother was reported missing. “She went for a walk this morning and she hasn’t returned,” the eldest girl said. “We were all sitting at home getting ready for school and we were just … getting worried. Then the police car came to talk with Dad.”

Allison kissed her daughters goodnight the night before. She sang her eight-year-old daughter to sleep. Allison wasn’t home when the eldest daughter woke the following morning. She said her father had a Band-Aid on his face when she rose at 6.30am. “He said he scratched it about three times in a row because he had a really old razor,” she told detectives. Allison’s girls thought their mum might have tripped on a walk. She might have twisted her ankle and couldn’t get up. They thought her phone might be dead: “Because she was always running out of batteries.”

It’s a courtroom divided. A row of Baden-Clay family members at the front left side of the gallery, sure of Gerard’s innocence. Rows of Dickie and Dann family members to the right, sure of something else. In between them are three absent young girls who watch the Disney Channel mostly to lessen their chances of seeing their mum’s face on television. Only one person in the room knows the truth: Gerard Baden-Clay, seated in the dock, fit and trim, neat hair, suit and tie, scribbling notes.

The defence builds a picture of Allison that shows her as a withdrawn mum struggling with depression. Gerard’s father, Nigel, has spoken of the “dull nature” of Allison’s dress sense. “I think that was a sort of indication that she was a depressed person,” he said. Gerard’s sister, Olivia Walton, recalled Allison being so depressed it affected her abilities to care for her kids and her home. Allison’s best friend, Kerry-Anne Walker, saw a different side: “On her best days as a mother, she was twice the mother I am. If she was talking about feeling down, it was just trying to cope with all the things we had to cope with as mothers with children. She was great in those months before she died, she was fantastic.”

The prosecution has outlined Gerard’s extreme debt; the pressures the Queensland floods of 2011 put on his Century 21 prestige real estate business; the phone call Gerard made to a life insurance company the day after his wife’s body was discovered.

Gerard’s brother, Adam, tries to bridge the divide. He’s shaken hands with Geoff Dickie. He nods warmly to Jodie, sitting beside Priscilla again today, and she doesn’t know how to respond. So much water under the bridge.

Jodie recalls how exasperating and puzzling it was for Allison’s family not to have Gerard join them at the search HQ at the Brookfield Showgrounds where hundreds of police, SES and neighbours were co-ordinating the search for his wife. She recalls standing beside Priscilla when she phoned Gerard in the days of Allison’s disappearance and discovery. “She wanted to see the girls,” she says. “And she was literally begging this man, ‘Can I please come around, I just need to hug the girls’. He didn’t think it was appropriate. [Towards the end of the search] the last thing he’d said to Priscilla and Geoff was, ‘I’m not speaking to anyone anymore because my lawyers told me not to speak to anyone’.”

Jodie knew the defence would play the depression card, for the same reason she knew Allison could never leave Gerard. “We know she had anxiety and depression,” she says. “But she’s not the dumb wife who let her husband have an affair for four years. She was trying her damnedest to make her marriage work … She was terrified he would make her out to be a nutter and she wouldn’t have got access to the kids. What control would she have had? She was an intelligent woman. She would have known how it would play out. What more control do you need than saying, ‘You’re going to lose your kids if you walk’?”

Through courtroom video screens the prosecution flashes a photo of Allison’s dead body. She was found with a diamond ring and a wedding band; with three-quarter length pants, socks and sneakers, a jumper wrapped around her neck, twigs and leaves through her hair. “I just think, she’s not there in those court photos,” Jodie says. “That isn’t her. It really isn’t. She is so gone by then. That is just a body.”

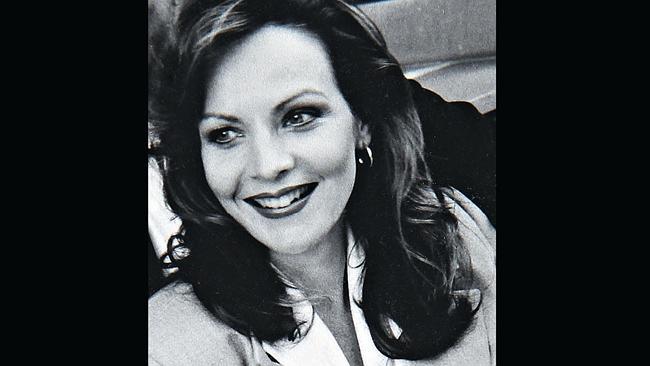

Allison Baden-Clay was a woman who sang Away in a manger to soothe her girls to sleep. She was her own infectious laugh, her own quiet giggle. She was the girl joking that her thighs were too big to be the ballerina she dreamt of becoming. She was the girl who studied five foreign languages. Miss Brisbane 1994. She was the mum going OTT for her daughter’s birthday party. She was the girl scribbling life goals in her diary about the job she would one day have, the weight she would one day lose, the children she will always love. She was the woman writing in her handwritten journal about her husband’s affair on the day before she disappeared: “Did she ever say, ‘I feel bad because you’re married’? Do you regret the whole thing or just being caught? Were you prepared to live with the guilt if I hadn’t found out? Afterwards why so mean?”

An aerial photo of Brookfield is pinned to a whiteboard near the witness stand. Jurors take notes as they study evidence flashed on their own personal screens, tissue boxes and water jugs by their sides. Regular court punters scribble notes in books, whisper knowingly to each other about complex legal matters. The court breaks for lunch and the punters lay down handbags, scarfs and jackets to secure their seats.

Jodie and her family walk outside the court, snapped by photographers, followed by TV cameramen. “Why?” wonders Jodie. “What the hell was it about Al that has captured the public? I think she’s everyone’s best friend. I think she’s everyone’s daughter. For some reason, they gave a shit about Allison. The Brookfield thing maybe. It’s the perfect suburb. Everyone would love to live in the perfect suburb. Which is why Gerard lived there. It was always image management with him. He couldn’t afford to live there. He was renting. But I think people just thought, ‘Oh, this doesn’t happen in these areas’.”

An estimated 35,000 Australians are reported missing each year. To be in Brookfield during the search for Allison Baden-Clay was to be inside a Hollywood movie where a small town goes into lockdown as police and officials search for something, anything, that might turn the tide in the story’s drama. Each day, Geoff, a retired firefighter, and Priscilla would turn up, hopeful, to the search HQ tents with home-cooked food for the search parties.

The dark rumours built with every fruitless day of searching. Whispers. Sightings. Assumptions. Lies. The city of Brisbane was superglued to the search, then the state of Queensland, then the country.

“I literally had to drag myself out of bed this morning to come to court,” Jodie says. “But we come because of the same reason we all turned up for all those days at the search site. People had to see she was loved.” Jodie ducks into an alleyway cafe, orders a pumpkin soup before the next court session begins. It wasn’t lust or vengeance or deceit or desperation that killed Allison Baden-Clay, she believes. It was something far more common. “Control,” she says.

She believes Allison was killed by the thing Jodie has devoted her career to ending, domestic violence that takes many forms; takes the lives of, on average, one Australian woman each week. “I had been saying very clearly for five years, to my mother, to my husband, ‘Look at her’,” she says. “The isolation. The lack of financial independence. Unable to make decisions for fear of making the wrong decisions. The fact she didn’t have many friends anymore. This was a girl who was highly social, had a great network of friends, was highly intelligent. But she was slowly eroded. Her self-esteem was eroded down to the point where she didn’t feel that she could do or say anything for fear of the repercussions. Psychological stuff.”

She recalls Gerard disengaging himself at Dickie family functions; giving his wife and kids orders not with his voice but with his eyes, with a flick of his fingers. “It was so controlled in their lives,” she says. “If Allison came and spoke to me he’d be on me in five minutes. Our last Christmas I had five minutes to speak to her without him standing beside me. Because he feared what I might say to her. That’s why the only times we spoke was at a shopping centre or at a supermarket where he wasn’t around.

“That’s how she was with a lot of her friends that she wasn’t allowed to see. Even with her best friends. She didn’t tell Kerry-Anne about the affair [between Gerard and Toni McHugh, which Allison knew about by 2011] because she knew Kerry-Anne would want to say, ‘What the f..k are you doing with this idiot?’ But she was probably thinking that would make it worse. She’s thinking, ‘I’m trying to handle this’. He’s extremely good at the pull-back. Every time she said she’d had a gutful, he pulled her back in.”

But Allison was trying to get out at the time of her death, Jodie believes. “She was starting to try and get her own money. She was creating a ballet school. She was starting a business that she didn’t want him to know about. She never said she was going to leave but I do think she was getting strong and I believe that the strong Allison wouldn’t have put up with this. And she did stand up.”

A thought strikes her and she pauses, her face grim. “If she didn’t stand up she wouldn’t be dead. She found her strength and she ended up fighting to her death.” She smiles when she thinks about the strength of her cousin that nobody ever mentions. The strength it took for her to walk, head high, into the offices of Century 21, returning to work to help save a dying business knowing full well the staff knew of her husband’s affair.

But if Jodie could go back to the night of April 19, 2012, she would tell Allison not to be strong. “Play nice,” she says. “I would have said, ‘Play nice for as long as you can, plan your exit strategy and then, go hard. But until you’ve got a clear line of sight, play nice. Say, “Yes sir, no sir.” Wait for your moment and go. If you’re getting stronger, don’t let him know that. Still play humble, play dumb, play stupid.’ Her exit plan didn’t work.”

She takes a spoonful of pumpkin soup. She checks her watch. The murder trial of Gerard Baden-Clay will resume in 15 minutes.

A botanist will take the stand to discuss the various leaf types found in Allison’s hair, which might yield clues about where she was killed. The two women in the back row of the public gallery will huff and puff and sigh rudely about the lack of thrills and spills in the scientist’s testimony. The two women will want high drama, they will want blood, and they will get it two days later when Gerard Baden-Clay takes the rare and confident step to testify in his own defence, swearing on the Bible that he did not murder his wife; that her fingernails did not scratch his face; that he did not dump her body beside Kholo Creek. But the jury won’t believe him. The final chapter in the disappearance of Allison Baden-Clay will end with her husband being sentenced to life for her murder.

But for now Jodie spoons her pumpkin soup. Something makes her give a half-smile. “I’m forever amazed that Allison, who’d never fight or hurt anybody, fought,” she says. “She scratched his face. He will be hating her for that. If she hadn’t scratched him he would have got away with it. Police, everyone said it, that scratch. As soon as they saw that scratch, they knew.

“She would never ever in her life physically have had a fight with anyone. She would never have done that. So the fact she did that, and marked him, and he had to sit there and figure out a way to cover up those scratches, I am just so forever impressed by the strength that it took for her to do that. He, who controlled everything, couldn’t control her hand.”

National Violence & Sexual Assault Hotline 1800 200 526