What, if any, parts of our modern life will survive 1000 years?

The best way to consider how we might live a thousand years from now is to go back a millennia to 1025, a time that predates the Norman Conquest of Britain.

Have you ever wondered what our world might look like a thousand years into the future? Even citing the date 3025 seems to me, a Victorian, more like a postcode than a far-off point in the continuum of humanity.

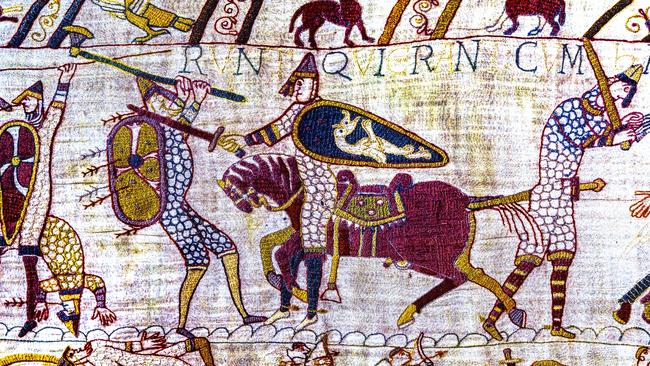

The best way to consider how we might live a thousand years from now is to go back a thousand years to 1025, a time that predates the Norman Conquest of Britain. One of our main insights into this world is captured via a much lauded Scandinavian poem (written in Old English) called Beowulf, which tells a story of love, courage, bravery and battle.

Within half a century the Norman invasion of Britain (1066) delivered not just a new administration and a fusion of the English and French languages, but also the Domesday Book – which to me always seemed part census, part audit for the purposes of taxation assessment. Tax, it seems, is a remarkably robust concept that is able to withstand the ravages of time.

Ask what personalities might endure for a thousand years in the public consciousness, and the answer is political figures who connect a name (or brand) with a characteristic – such as, say, William the Conqueror. Few today have any awareness of Harold the Defeated. Good branding goes a long way to making an impact and being remembered.

The lessons from the past millennium are that language changes by conquest and/or by evolution. Could we understand anything said in village chatter in England in 1025? Possibly very little. Global travel and migration are likely to hasten the fusion of languages over the next thousand years. Some words will recede, as will the concepts with which they are paired. Take, for example, the word and the concept of fealty, meaning loyalty to a feudal authority. Fealty is not used in everyday language because everyday life in 2025 is far more individualistic than was the case a thousand years ago. We are all individuals beholden to no one, you see.

I could also add to fealty the term chivalry, which is fast losing favour due to changes in the relationship between men and women. Bravery, courage, honour and heroism are just as popular today as they were a thousand years ago, although there has been a migration of these concepts from the battlefield to the sports field. In times of peace and prosperity we make room for heroes.

It is doubtful that anyone alive today will be popularly remembered a thousand years hence, for good or ill. It is possible, I suppose, that a sovereign Australian nation will singularly occupy the Australian continent in 3025, although it is by no means certain. Less probable is the likelihood that we could understand the language, let alone the values, of our descendants 30 generations hence.

And so our world a thousand years into the future will surely have its heroes and villains, its taxation and audit processes, plus remnants of words that we may recognise as well as others that will be entirely foreign.

What I’m confident will prevail, however, is people’s love of children, the importance of family and, because we’re still likely to exhibit and/or suffer human traits, the squabbles and the vicissitudes of individuals making their way in life. Some things never change.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout