Was Keren Rowland an early victim of Ivan Milat?

For 50 years her murder has remained unsolved. Her devoted parents died without answers. Somebody knows what happened to Keren Rowland – so what are the police hiding?

It is a summer evening, Friday February 26 1971. The past few months have not been easy for 20-year-old Keren Rowland, but tonight she is happy. She has brought home a big balloon from the Canberra Show and is planning to join her younger sister, Christine, for a few drinks at the Statesman Hotel in Curtin. The plan is for Keren to meet Christine, her fiancé John Hibbert, and a family friend, Martin Burt, outside the city pharmacy where Christine works. At around 9pm Keren leaves the family home in Downer in her white Mini.

“Shortly after Keren left the house I heard the Mini backing out of the driveway and then I heard the motor stop,” her father Geoff will later tell the police.

“I waited for a couple of minutes and … walked outside and saw the Mini stopped in the middle of the road in front of our house. The vehicle did not have any lights on and I walked across to it and saw Keren looking into the rear-vision mirror and fixing her eyelashes. I said to her, ‘What’s happened? Has the car stalled?’ She said, ‘No, Dobs, I’m just fixing my eyes.’ I said, ‘You silly goose, you should have the lights on. You’ll get cleaned up.’ Keren laughed, turned on the headlights of the car, started the vehicle, said, ‘Cheerio, Dobs’, and then drove away.”

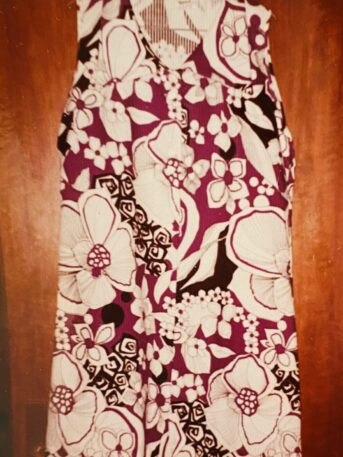

Keren pulls up outside the Central Pharmacy in Alinga Street 15 minutes later. She is wearing a mini-length cotton shift in a purple, black and white floral print and has been to the hairdresser’s to have her hair shampooed and set. When she gets out of the car Christine says, “Your hair looks nice” and asks what it is for. “For fun,” Keren tells her. What’s more, she has another appointment booked for the following Tuesday to have her hair set for a dance.

Keren’s life has not been much fun lately. She is five months’ pregnant and has broken up with her fiancé, who is now flaunting his relationship with another woman. Just a few weeks ago Keren was hospitalised with depression and even spoke of killing herself, but now she has a new job she likes at the Prosser heated pool and, in the words of the doctor who treated her, is “looking forward to the birth of her child”. Christine will later describe her sister as “happy and contented”.

Christine tells Keren to turn the Mini around and wait in Bunda Street while she and her friends go to fetch Martin’s Fiat 124, which is parked nearby. As they drive past Keren in the Fiat, Martin toots the horn, indicating that she should follow.

Moments later Christine and her friends in the second car make a fateful decision: by now, they agree, it is too late to drive to the Statesman Hotel, so they decide to go instead to the Hotel Dickson, which is closer to home.

Martin flashes his indicators and all three wave at Keren to let her know the plan has changed, but Keren just throws up her hands and giggles. Has she misunderstood?

As both cars head south on Commonwealth Avenue, Christine gestures at Keren to follow them onto King Edward Terrace, which will take them past the National Library and back over the Kings Avenue Bridge towards Dickson. As Martin drives, John keeps watch to make sure they don’t lose Keren. At this point she is no more than 100m behind. But as they cross the bridge and turn left into Parkes Way John notices that Keren is dropping back. He thinks about asking Martin to slow down to allow Keren to catch up but for some reason he doesn’t say anything.

Now things become confused. John realises that Keren is no longer following them. Looking back, Christine sees a “white or cream” Mini that could be Keren’s driving west along Parkes Way before taking the Rond Pond roundabout and heading east, away from the city. “Oh, there she goes,” Christine thinks. “Keren is in a huff because she thinks we’re going home.”

It crosses Christine’s mind that they should follow the Mini, but she tells herself that Keren is probably going to a friend’s place. Nevertheless, there is a “nagging worry” in her head; the sisters are very close and Christine hates the thought of Keren being upset with her. Martin pulls over and they wait for several minutes. When Keren fails to appear they give up the idea of going to the Hotel Dickson and head for home instead.

Geoff and his wife, Hazel, are surprised when Christine and her friends turn up about 9.45pm without Keren. Worried that she might have run out of petrol or that the Mini has broken down, Geoff suggests going out to look for her, but in the end they all agree that she is probably visiting a friend and will return soon. Martin drives home and at 11pm the others go to bed.

Geoff lies awake, listening out for his eldest daughter. At half past midnight, he and John drive to ACT police headquarters to report that she has not come home. At around 1.30am police phone the family home to say that Keren’s Mini has been found parked just off the bitumen on Parkes Way. The car is locked. There is no sign of Keren.

John, Christine’s fiancé, has known Keren for three years; they have been out together on double dates. He will later give evidence that he believes Keren “would accept a ride from a stranger as she was an extremely self-confident person” who would consider herself “able to handle any situation in which she might find herself”. Keren, he adds ominously, “didn’t appear to me to be a good judge of character”.

On May 13 1971, two and a half months after Keren went missing, her badly decomposed body is found 10km away in a pine plantation near the Air Disaster Memorial by a university lecturer who has gone there to read in the sun.

“The time between when Keren went missing and when she was found was a blur for us all,” says her brother Steve, who was then 16 years old. “Dad was just frantic because Mum and Dad both knew that something terrible had probably happened. There was no way in the world that Keren would ever have run off.”

Geoff Rowland searched tirelessly for his missing daughter, combing the area where her car was found, talking to anyone in Canberra who might have seen her, travelling to Sydney and Melbourne to circulate her description and chase down possible sightings.

Before moving to Canberra Geoff had worked as an assistant mortician in Sydney, living with his wife and children above the old Coroner’s Court in the Rocks. He had contacts in the police and understood how murder investigations worked, or ought to work.

“Dad put more work into that first five or six months than the police did,” Steve says. “First looking for Keren and then trying to find out what had happened to her. Travelling more miles, contacting more people, putting out more fliers.” After a fruitless trip to Sydney Geoff returned to Canberra, telling reporters it was “shocking, just walking around culverts and roadsides, searching”.

The ACT Police appealed for witnesses, and several came forward. A man driving home from the airport at about 9.25pm on February 26 recalled seeing a woman in a purple dress “with her hair done up at the back” walking along the grass verge about 30m ahead of a light-coloured Mini on Parkes Way.

“The thought ran through my mind that she was rather foolish to be walking along Parkes Way at that time of night, and I … thought that she may have had car problems,” the witness told police. “Because I was on my own, I didn’t stop.”

A female witness remembered seeing a “small cream-coloured car” parked in the grass next to Parkes Way at around 9.20pm. A second car was parked in front of it. “I thought I saw what appeared to be two people sitting in the front seat,” she told police. “I thought they were a courting couple.” She described the second car as “maroon … quite dirty … about nine or ten years old” with non-ACT plates.

A couple in a green Torana described seeing a blue or dark car with NSW plates pull over on Parkes Way near a light-coloured Mini at about 9.30pm. The driver had “long hair”. The female witness saw a girl in a pale miniskirt walking towards the dark car and remembered saying, “She will be all right, it’s a woman driving” and her boyfriend saying, “No, it’s not. It’s a bloke.”

Several reports were received of “suspected perverts” attempting to accost women in Canberra and nearby Queanbeyan in the days before and after Keren vanished. They included the driver of a “dark-coloured car with NSW registration plates” who had attempted to accost a woman in Civic three days earlier.

Nearly six weeks after Keren’s disappearance Labor MP Kim Beazley Snr asked in parliament whether police believed Keren had been murdered and if “adequate homicide forces” were available to continue investigations. The Minister for the Interior, Ralph Hunt, said 25 police were looking for Keren but refused to say whether it was being treated as murder.

Three weeks later another witness, Charles Hawes, came forward to say he had been driving with his wife on Fairbairn Avenue at 11.20pm on February 26 when he saw a “girl … about 18-20 years” running away from a dark-coloured sedan “similar to a 1962 Holden” that was parked on the wrong side of the road near the gun gates entrance to the Duntroon military college. The girl was running through knee-length grass in the direction of Canberra. According to the police report, she “did not indicate that she was in any trouble so [the witness] did not stop”.

This sighting – which put a woman resembling Keren between where her car and her body were found – was potentially the most valuable information the police had been given but, like the rest, it led nowhere. Neither Hawes nor his wife were called to give evidence at the coroner’s inquest in September 1971.

Within three months of Keren’s body being found the number of police reported to be involved in the investigation had dropped from 25 to four, one of whom was Detective Sergeant Colin Winchester, who would be assassinated outside his Canberra home in January 1989.

Statements from key witnesses, including one from Keren’s father, were taken only months after she disappeared. ACT detectives did not bother to take a statement from Keren’s mother, whose evidence might have shed important light on her daughter’s state of mind.

The autopsy left more questions than answers. Crucially, part of the hyoid – a small U-shaped bone in the throat that is often fractured in homicides by strangulation – was found to be missing.

There were other mysteries. The police confirmed that Keren’s car had run out petrol, yet she had filled up only two days earlier. The Mini had a locking petrol cap and the key was on Keren’s body. Keren’s friend Margaret Davison had use of the car on the day Keren disappeared but the mileage was not enough to explain the empty tank.

And what happened to the gilt bracelet Keren had bought at the Canberra Show to give to the sister of a friend on her 12th birthday? The bracelet, engraved with “Lynette”, was not with Keren’s body and, despite police appeals for information, was never found.

The autopsy report referred to the “pinkish discolouration” of Keren’s teeth – a condition then associated with strangulation but also with barbiturate poisoning, drowning and “septic abortion”. (According to the AFP, the “pink teeth” phenomenon is now regarded as an “unreliable” indicator for possible causes of death.)

Drowning was immediately ruled out and several witnesses, including Keren’s doctor, gave evidence that she had never discussed having an abortion. That left suicide by an overdose of barbiturates or what Coroner Kevin Dobson, in findings handed down on October 1 1971, called “murder or other foul play”. No trace of barbiturates was found in or under Keren’s body, which was lying on two rocks, an uncomfortable position that could only be explained if she had fallen instantaneously unconscious while standing – a suggestion the coroner found inherently implausible.

The police found several items, including Keren’s handbag, shoes and a pen, between her body and the dirt track, prompting the Coroner to conclude that Keren’s body had been “dragged to the position in which it was found”.

In spite of this, the Coroner asserted that the evidence was not strong enough to support a finding that Keren had been murdered, and instead recorded an open verdict.

Could the gilt bracelet engraved with the name “Lynette” have been taken by her killer as a trophy? At the 1972 Canberra Show police displayed a life-size dummy of Keren, in a wig and clothes identical to those she was wearing on the night she disappeared, but it failed to jog anyone’s memory. A $2000 reward for information was withdrawn a year later, but after a complaint by Keren’s father it was reinstated and increased to $10,000. The reward remained unclaimed and eventually lapsed.

In October 1973 the head of the Criminal Investigation Division, Inspector Reg Kennedy, told reporters he had been to Sydney to question a construction worker who had lived in Canberra in 1971 and was “thought to be involved” in Keren’s death. “There is a distinct possibility we’ve found our man,” he was reported to have said. But no charge was ever laid.

According to Steve Rowland, his father always believed that if Keren had been found a few metres to the east, the case would have been solved as the NSW Police would have had jurisdiction. “Dad maintained that the ACT Police had little experience [of murder investigations] and were learning as they went,” he tells The Weekend Australian Magazine.

“It was heartbreaking for both Mum and Dad not to be able to put some closure to the murder of Keren and her unborn baby. Dad was not a physically well man at that stage of his life, but it didn’t stop him from pursuing every possible lead. He often told me that while he liked a number of the detectives who worked on Keren’s case, he had little faith in their ability to carry out an investigation of this type.”

Keren’s parents died without knowing what had happened to their beloved eldest daughter; Geoff in 1998 at the age of 71, and Hazel 11 years later at the age of 80. But Steve stayed on the case, requesting regular updates and pushing for a meaningful reward to be offered.

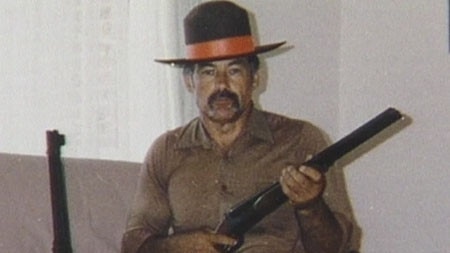

The 1996 conviction of Ivan Milat for the murder of seven backpackers in the Belanglo State Forest between December 1989 and April 1992 raised the possibility that Milat might be responsible for other unsolved murders.

In April 1971, just weeks after Keren disappeared, Milat picked up two female hitch-hikers at Liverpool in south-west Sydney, and took them to Goulburn, an hour from Canberra, where he raped one after threatening to kill them both. When they asked him if he had done this before, Milat reportedly answered yes – that was why he always carried a knife and rope in the car, in case the opportunity arose.

The possibility of Milat having murdered Keren was a frequent topic of discussion within the Rowland family. Steve’s cousin Andrea grew up in Sydney. On the Monday after Keren went missing, Andrea’s father had brought home a copy of the Sun with a picture of Keren on the front page. Andrea, then 11 years old, spent the evening sobbing in her room, praying for her cousin’s safe return. Keren’s murder made Andrea’s parents obsessively protective towards her, even into her twenties. She left Australia in 1986 to study in the UK and later married Hugh Hughes, a police officer.

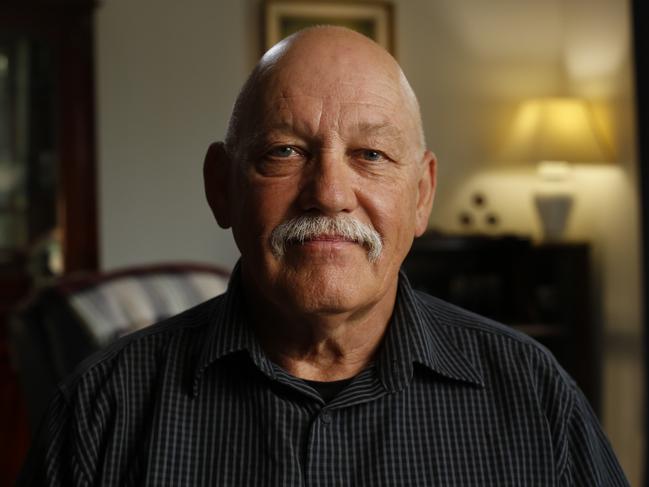

Hughes recalls talking informally with Geoff Rowland about Keren’s murder, but it was not until 2017 that Steve asked for his help. By then retired from his job as a detective sergeant with Thames Valley Police, Hughes agreed to look at the investigation. After studying the press cuttings kept by Keren’s father, Hughes wrote to the AFP Commissioner, Reece Kershaw, and the Home Affairs Minister, Peter Dutton, and drafted a series of questions for ACT Police.

To Hughes, Milat seemed an obvious suspect. “Milat was looked at for the 1973 murder of a woman in Albury, four hours from Canberra,” he says. “Alarm bells should have been ringing for ACT Police after he raped a woman in Goulburn. My belief is they did not look at Milat for Keren’s murder in 1971 and they know they should have.”

On January 11 1995 detectives from Task Force Air, which had been set up by the NSW Police to investigate the backpacker murders, spoke to detectives handling Keren Rowland’s case. According to a former senior officer who discussed the matter with Hughes, the NSW investigators were only shown the AFP files after signing a non-disclosure agreement. There had to be a non-disclosure agreement, Hughes says, because ACT Police had not told the family their most significant discoveries.

Yet work done by Task Force Air suggested at least five reasons for considering Ivan Milat a possible suspect in Keren’s murder. One, Milat’s crimes often coincided with significant events involving women in his life, and he had lost his sister Margaret in the weeks leading up to Keren’s disappearance. Two, there were similarities in the way Keren’s body and the bodies of his other known victims were found. Three, a beer bottle had been found near several of Milat’s known victims, and one was found near Keren. Four, Milat was known to be offending in the area around the time of Keren’s disappearance. And five, Milat’s work records indicated he had been working near Queanbeyan at the time of her disappearance.

In June 2019 achance Google search alerted Andrea that Keren’s case files had been lodged in the National Archives – highly unusual for an open murder investigation. The files had been sitting there for a decade, but when the family applied to see them they were swiftly designated closed and taken back by the AFP. A note on each file says “withdrawn long term”.

As the 50th anniversary of Keren’s death approached, the family was still battling to obtain information from the AFP about her case.

In early 2020 a letter from Andrea to Kershaw prompted a call from AFP Deputy Commissioner Neil Gaughan, who agreed to a meeting the next time she and Hugh were in Australia. At the meeting, in March 2020, Gaughan promised that Keren’s case would be fully reviewed by the unsolved homicide team and that the AFP would help with a TV program about Keren’s disappearance.

It was not until April 2021 that Gaughan wrote to Steve saying the review of Keren’s case was in its final stages and would be reviewed by himself, the superintendent of criminal investigations and the deputy DPP. In July the family was promised that within four months they would have news about a fresh reward for information and the AFP would share everything it had on Keren’s case. Sixteen months later they were still waiting.

Sporadic meetings took place but by the start of 2023 Steve had had enough. “They would tell me that they hadn’t got very much material to do with Keren,” he says, “and the next time we had a meeting, they must have forgotten all about it. They’d say, ‘Oh, we’ve got so much stuff up here.’ It was just ludicrous … either they were really, really worried about the way the case was handled, or else they knew something and didn’t want to tell us. I can’t think of any other explanation.”

Then in July an AFP liaison officer rang Steve with news of a breakthrough: a forensic geo-profiler (someone who uses location, residence and workplace to narrow down possible suspects) had come up with a POI (person of interest). The liaison officer could not give him the name of the POI but promised to arrange a meeting with the head of the unsolved homicide team, Detective Superintendent Scott Moller, who would answer questions – including whether the POI was Ivan Milat – in person.

When Steve rang Hughes and told him he had been promised the name of the POI, Hughes immediately jumped on a plane to Australia. “I think they were really shocked when Hugh arrived because they knew he wasn’t in the country beforehand,” Steve says. “Scott Moller spoke for at least half an hour on the trouble they were having getting a reward … and then he said, ‘What else would you like to know?’ and I said, ‘Mate, the only reason we’re here is to hear who your person of interest is’. And he said, ‘We don’t have a POI … Our geo-profiler has a POI … We’ve never had a POI.’” When the family asked for the name of the geo-profiler’s POI, their request was refused.

Hughes suspects there have been numerous POIs over the years but says he was told by the former senior NSW officer that the only suspect ACT police had for Keren’s murder in the late 1990s was Ivan Milat. (Task Force Air identified 16 unsolved murders for further investigation; in 13 no evidence was found to implicate Milat but in three – including Keren’s – detectives felt there was cause for suspicion.)

In November 2022 staff and students at Newcastle University’s School of Law and Justice had begun reviewing Keren’s case, ostensibly with the AFP’s blessing, but this project ended ten months later when ACT Policing abruptly withdrew its cooperation.

For the Rowland family it was the last straw. “I think we’ve got to the stage now where we absolutely have no trust in anything they say,” Hughes says. “We’ve lost all trust in the AFP.”

In response to questions from The Weekend Australian Magazine, a spokesperson for ACT Policing confirmed that “approximately 30 persons of interest” had been investigated by police as potential suspects in Keren’s “disappearance and death” but maintained there was “no compelling evidence to implicate any particular person in the crime”. The spokesperson said that Milat was and remains a person of interest in Keren’s murder and that “this line of enquiry is still under investigation”.

Last month Steve sent a letter to the AFP Commissioner, the ACT attorney-general and the ACT police minister calling for an independent review of Keren’s case and for the police to deliver on their promise of a reward for information. To date the only reply he has received is an email from a detective sergeant in the unsolved homicide team expressing regret for the family’s loss of “trust and confidence”.

On February 26 1983 a short item appeared among the family notices in the Canberra Times: “In memory of our daughter Keren Ellen Rowland, lost to us on 26th Feb 1971, still unsolved, can anyone help? Sadly missed, loving memories. Mum and Dad.”

ACT Policing states that it “believes there are people who know what happened to Keren” and points out that “a number of potential persons of interest … are still alive”.

Nearly 53 years after Keren was murdered, her family remains desperate for answers.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout