Trent Dalton’s Tales From the Bunker series finale

For our ‘Tales From the Bunker’ series finale, hundreds of readers have written in to share their love stories. Here’s the pick

This is the story of nine letters of love written in isolation. Nine love stories. Most of them are sad and beautiful. One is about faith and three are about true love. One is about chocolate bars and one was written from prison. One was written for Hamlet, one is about a blind date and the last one says too much about me.

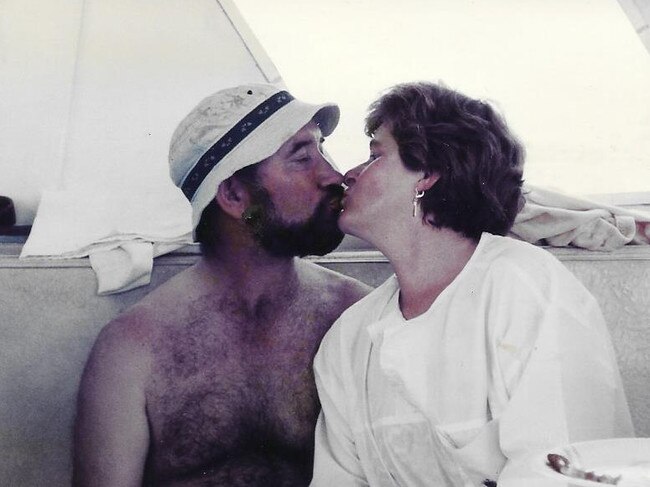

The first love story is about Janet and Bryn Walters from Fremantle. It deserves a title. I’ll call it Nos Da Fy Cariad. Janet writes in to say something important about how she’s been spending her days in blissful isolation with her husband Bryn. Before Covid-19 they woke at 5.30am every day to go to the gym for a morning swim. But now the virus has given the two long-time lovers and retirees the perfect excuse to stay in bed. “We don’t have to rush and can stay in each other’s arms and snuggle a bit longer,” Janet writes. Then they go for a morning walk; they get their old street directory, pick a random neighbourhood to explore and set off into the great suburban unknown. “We love looking at the old Fremantle houses,” Janet writes. “We walk hand in hand even though we are in our 70s and Bryn gives a little skip every now and then.”

Bryn’s always reliving his rugby days, making imaginary jinking runs through the street, palming off the hulking props in his memory. Then it’s home for breakfast – “Bryn is a die-hard beans on toast man,” Janet says – after which he potters. He gardens and he makes a mosaic in the garage and he plays their favourite Johnny Mathis records all day. “Bryn blows me a kiss whenever he catches my eye,” Janet says. “The day passes in the companionship of someone to whom you have been married for nearly 50 years. We are lucky that we have a view of the ocean from the top floor and at 5pm it is time for a sundowner on the top balcony, watching the ships in the harbour. We sit with a glass of white wine and count our blessings. How lucky we were to have found each other. We met and married within six months. We did not have children. How blessed we have been to have had good jobs, have a roof over our heads and food and wine in the fridge, good friends and neighbours. We hold hands and sit lost in wonderful memories as we watch the sun set. Every night we wrap our arms around each other, say good night with a kiss and a snuggle.”

But then there’s a two-line gap in Janet’s love story letter. A writer’s pause. I’ve done that myself. A breath of air for the reader. A moment to contemplate all that’s come before in the text, to enhance what’s coming next. A realisation. A revelation. A truth.

“This is how it would be, Trent, but it is in my dreams,” Janet writes. “Bryn had a cardiac arrest in 2018 while we were on holiday in London. It was completely out of the blue. He was fit, active, good diet, no symptoms at all. He was resuscitated but never regained consciousness. We came back to Australia thanks to good insurance and Bryn died shortly after we got back to Perth. It is 18 months ago but to me it is as though it were yesterday. It would have been our 50th wedding anniversary in January. I have grieved before when Mum and Dad died; my lovely only brother; dear, dear friends and even my dog. But this is the absolute worst grief ever, the pain does not go away and who thought you could cry so much without dehydrating and shrivelling up? I think friends think I should be over it by now, but this broken heart isn’t healing very quickly.”

The virus only made things worse. She needs Bryn now more than ever. He made uncertainties certain again. He got her back to sleep when she woke in the night. Now she wakes in the night alone, saying the same words to her one true love. “Nos da fy cariad,” she says. They are Welsh words for her beloved Welshman whose full name, Brynmor, means “hill by the sea”. “Nos da fy cariad,” she says to herself at night. Nos da fy cariad. Nos da fy cariad.

“I will be moving later this year to a retirement village,” Janet says. “I have photos to go through. Haven’t managed it yet, but this lockdown will make me focus on things I’ve been avoiding. The morning and night-time snuggles are with a pillow. The other side of the bed looms empty and large. I kiss the photo of Bryn goodnight and talk to him, telling him what I have done or will be doing, and saying how much I miss him. We had a wonderful life together, not all moonlight and roses but we weathered the storms. He was my wonderful Welsh wizard and he believed in magic. He always said the best magic was when we met.”

Then Janet’s letter comes to an end with a single and final perfect line. “Nos da fy cariad,” she writes. Welsh words for her beloved Welshman. Nos da fy cariad. Goodnight my love.

Six weeks into lockdown and I’m writing these words while trying to show my daughter how to express 33 over 5 as a mixed fraction. Damn. Really shouldn’t have spent all that time in maths class sketching images of Winnie Cooper from The Wonder Years. I intended to model my isolation relief-teaching career on Robin Williams from Dead Poets Society, but in the space of a single morning my teaching style has turned full-scale De Niro: “You talkin’ to me? You talkin’ to me? Well, then who the hell else are you talkin’ to?”

My wife takes a break from work downstairs. “How’s it all going up here?” she asks.

“I’ve been a teacher for two hours and already I wanna go on strike over working conditions,” I say. I’m thinking about that teacher at my kid’s school who just clocked up 50 years. I’m gonna send her a box of roses, and maybe a box of whisky.

Another daughter is at the kitchen table reading an Anzac Day worksheet about Simpson and his donkey. She needs to list 10 qualities that John Simpson Kirkpatrick must have possessed to do the things he did at Gallipoli. She’s listed nine qualities so far, six of which were technically covered by the first one she listed: “Bravery”.

“What about love?” I say.

Love for his country. Love for humanity. Love for that brave donkey.

Always comes back to love. So many reminders of it in the isolation. It’s been the overwhelming theme of all the letters we’ve received in the bunker. Some 592 letters across six weeks of isolation, maybe 300 of them about love. Love between a widow and her late husband. Love between mothers and daughters. Love between lifelong friends. A love of automobiles and the open road. The love of music. The love of books. The love of Shakespeare. John Slee from Dunsborough, Western Australia, is 88 years old and lives with chronic respiratory disease. He’s about as vulnerable to Covid-19 as a bloke can get but what he feared more than dying from this feckless thug of a pandemic some three weeks ago was going before he had gotten around to reading Hamlet. “I haven’t got much time,” John says. “Locked up in my bunker here, I bit the bullet.” He read it. He loved it. Another box ticked before the clock ticks its last.

Doubt thou the stars are fire

Doubt that the sun doth move

Doubt truth to be a liar

But never doubt I love.

In Perth, Sarah writes about the love of her brother in England. She writes about wanting to hold him more than ever before but there are oceans between them and there are restrictions that won’t be lifted in time for his funeral. Her brother died from Covid-19.

Jack writes a love letter to his wife from Wacol Prison in Brisbane’s west. He’s in his 60s. A white-collar criminal with three adult kids and a loving wife who stayed by his side when the judge said he would serve 20 months of a four-and-a-half-year sentence. Sorry wouldn’t begin to describe how he feels for what he did to his family. Sorry wouldn’t begin to describe how he feels about the events of mid-December, when his wife broke the news that she had been diagnosed with cancer, which she would have to endure alone.

“Then, just as my wife was working through her treatment, self-isolating because of the cancer, Covid-19 came upon us,” he writes. “Now she really is on her own.” And that’s a different kind of prison for Jack. The prison of regret. The prison of longing. The prison of his own thoughts that place him every day by his wife’s bedside, telling her the same words over and over again in his mind that he cannot say to her in person. Everything is gonna be all right. Everything is gonna be all right.

Moyra writes about a widower who once met a divorcee. Two long-distance lovers. “They first met on a blind date organised by a mutual friend,” she says. “He was 67 and she was 60. The attraction was there from the start, but they lived in different states. They very quickly learnt how to communicate via text and email, getting their heads around this new scary technology. It was worth it. He flew to her. She flew to him. And so it went on, wonderful comings together as they learnt about each other, in body and mind. They could not believe the quantity and quality of the sexual relationship they experienced; after all, you are not supposed to enjoy it at their age. But it just kept getting better and better. They would often look at one another and shake their heads, helpless with laughter. Wonderful holidays followed: Scotland, Spain, Portugal and twice to Italy. This week is the 12th anniversary of that blind date. They are now aged 79 and 72. They communicate daily by phone and text and FaceTime. She sends him a ‘song of the week’.”

Then comes Moyra’s pause in the letter. “He has a chronic lung condition and is very vulnerable to infection,” she writes. “They don’t know when or if they will meet again.” Then one last gap in the letter. “Don’t know where. Don’t know when.”

In Lake Macquarie, Kerry writes about her daughter, Jenny. Kerry’s so proud of how Jenny has carried herself through Covid-19. She’s been living alone, having survived a marriage beset by domestic violence. She’s a social butterfly who struggles with isolation. “Like many, Jenny’s job suddenly requires her to work from home,” Kerry says. “Her initial response is, ‘I think I’ll still go in’. I gently suggest that’s not possible.” Kerry wants to cuddle her daughter in that moment but knows that’s not possible, either. “Week two, Jenny makes dashes to family and friends to supply toilet paper,” Kerry says. “Her superpower is her compassion. As her mum I see this action delivers her some contact as well. Her job requires her to do contact tracing for Covid-19 and to see if travellers are self-isolating. She’s the recipient of gratitude but also astonishment and anger. Her colleague comments, ‘It’s sad to know some of these people we are calling and talking to won’t be here in a month’. Normally I would cuddle her in that moment.”

Week three in isolation, Jenny starts to adapt, but then a health scare. “A marker for cancer was elevated,” Kerry says. “More tests to follow. Normally I would cuddle her in that moment.”

In week four, Jenny makes a Zoom video call with her mum and extended family. During the call, Kerry watches Jenny look over her shoulder instinctively as though someone’s coming from behind. Like, “Is her husband about to end the call?” Kerry says. “He died, but the aftermath of domestic violence lives on. Jenny is resilient: ‘I survived isolation for longer in my marriage. I can do this’. Normally I would cuddle her.”

Then comes Kerry’s pause. Then comes the truth of isolation, in all its forms. “Yesterday, Jenny awoke to sirens,” Kerry writes. “A white sheet was draped over a tree across the road. A neighbour had committed suicide. Yesterday, I did cuddle her.”

Rabbi Gabi Kaltmann writes a love letter to his community in Hawthorn East, Melbourne. He writes about the recent Passover, the Jewish holiday that’s often described as a holiday of freedom. This year’s Passover felt anything but free. Rabbi Gabi normally hosts the traditional Passover feast – the Seder – at his own home, opens it to anyone from his community who might accept his invitation. “This year there wasn’t anyone to invite,” he says. “Leading up to this usually joyful holiday, I became quite dispirited as the calls started streaming in from community members who had lost their jobs, or savings in the stock markets, and now couldn’t even see their grandchildren.” The funny thing is it’s usually Rabbi Gabi actively making contact with his community members, encouraging them to return to the synagogue to connect, communicate, come together. Now his phone won’t stop ringing. Fear and sorrow always on the other end of the line. “Now I’m lamenting with them, trying unsuccessfully to find some reason as to why G-d is putting us through this test,” he writes. “The best I came up with was, ‘We are all in this together’.”

Then came the late-night call that felt like a breaking point. “A Holocaust survivor, 98 years old, had passed away and I was asked to officiate her funeral,” he says. “Due to social distance regulations no more than 10 people were allowed to attend. I agonised about how I was to console this family that had just lost their matriarch. This woman survived German slave labour camps and now, because of this silent killer, was unable to have her grandchildren and great-grandchildren at her farewell.”

He took it back to where it always comes back to. Love. Family. Connection. We are all in this together. Then he went home to his own family. He hugged his four kids, all aged under five. He hugged his wife. He prepared for the two weeks of Passover and he began to dread the school holidays.

“What am I going to do for two weeks locked in the house with my kids, especially over Passover? Is my Passover Seder going to be 10 minutes because of nappy changes, and bedtime will be in the middle of it? But then, incredibly, without guests, my wife and I had the most wonderful two weeks locked up at home with our children. Our Seder was a lively event with re-enactments of the exodus of Egypt, as well as long speeches and songs from my three-year-old who sang way past his bedtime. I even dressed up as Moses one night. I saw the silver lining in this turbulent time. I finally had time to be fully present with my children.”

Here’s another love story that deserves a title. Let this love story be called Nothing From Fitzy. The story of two long-time mates at opposite ends of Australia. Cork and Fitzy. Cork lives in Far North Queensland. “Closest capital city is Port Moresby,” he says. Fitzy lives in Gippsland, Victoria. On April 13, Cork received a text from Fitzy wondering if he’d received the gift he posted. Cork hadn’t. “Since that day I take Fitzy on my journeys to the post office with the aid of short videos that I SMS to him,” Cork says. “Each video includes the opening of the PO box showing him the mail that has arrived or an empty PO box.” So far, each video has sadly ended with the same words from Cork: “Nothing from Fitzy”.

“After a few videos my friend alerted me to his belief that his gift had been lost by a ‘mindless bureaucracy’ and my daily updates were becoming ‘painful’ for him to watch,” Cork writes. “Not wishing to cause my friend further emotional pain I’ve commenced taking him on other outings on days I don’t visit my PO box. I’ve taken him for Thai takeaway down by the edge of the waters of Trinity Inlet, the empty streets of Cairns and to put the garbage out. As my friend has aged he hasn’t been without his health issues and has developed diabetes. In our youth we would drive through Gippsland roads together to buy Sunday newspapers and supplies for lunch. My friend never failed to buy a couple of chocolate bars.”

So when Cork sent a video from the chocolate aisle of his local supermarket, Fitzy immediately registered the location’s significance. “I spent around a minute showing Fitzy what I knew to be some of his favourites,” Cork says. “I then selected two bars of good quality dark chocolate, on special, for myself.” Finally, Cork looked into his camera and sent his mate a bruising message: Nothing For Fitzy.

“I still take him to the PO box, but the message continues to be ‘Nothing from Fitzy’,” Cork says. “Often Fitzy tells me he loves me, but I’ve always given him good reason to hate me as well.”

And you’d be forgiven for thinking that might be all that’s left to say about the adventures of Cork and Fitzy, but then another love letter slides into the bunker. “You may like to know that yesterday the south-easterly trade winds were blowing through Cairns,” Cork says. “One of our large public gardens has a bamboo section. On days like yesterday the wind moves the giant bamboo. Leaves rustle and the bamboo groans as it rubs against itself. This formed my video to Fitzy yesterday. I’m pleased to be able to tell you Fitzy described the bamboo as ‘beautiful’. Yesterday, Trent, Fitzy loved me.”

The kids have finished school for the day. Class was dismissed with the ringing of a sound-effects bell I found on YouTube. I’m back down in the bunker writing these words with Keef, my late dad’s late pet stonefish who talks to me sometimes.

“Where’s number nine?” asks Keef from his big glass jar on the bookshelf.

“What’s that Keefy?”

“You said nine love stories?”

“I sure did, Keefy,” I say. “Nine letters of love. Nine love stories.”

“Well, I count eight love stories, if you include John Slee’s love for Hamlet as a story, which is a bit of a bloody stretch, and it looks like you’re wrapping things up here.”

I am wrapping things up. In truth, I could stay here forever. There’s almost 600 beautiful bunker tales in my inbox and I could turn each one into a magazine piece. Maybe I should turn all the letters into a book and post it to the National Museum of Australia marked with the words, “This is what Covid-19 felt like to us”. Or maybe I should just post it to Cork in Far North Queensland marked with the words, “Something From Fitzy”.

There’s good news filtering through the wires. We all did our bit so well. They’re relaxing the lockdowns. It looks like they’re gonna let us step back out into the light, with restrictions, of course. But I think it’s time to leave the bunker.

“This last bit right here is the ninth love story, Keefy,” I say.

“Waddya mean?” Keef asks.

“I mean you and I. All this rambling I’ve been doing in the early hours with you. That’s a love story. And this last bit here is my letter to you.”

“Weirdo talks to dead fish?” Keef says. “Hardly Gone With the Wind.”

“You’re not just a dead fish, Keefy.”

“I’m not?”

“Of course you’re not,” I say. “You know who you are.”

“Who am I?”

“You’re Dad. You’re my dear old man and it’s been real nice to come down here in the quiet hours and talk to you through this crazy pandemic.”

And Keef gives his long writer’s pause for effect.

“Yeah, it’s been nice talking to you, too.”

But no more talking now, Keef, because the kids upstairs want to go for a walk down to the park. The afternoon birds are squawking in the trees across the western suburbs. The autumn air is crisp and promising and the light is falling across another day. The light, Keefy, the burning and invincible light.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout