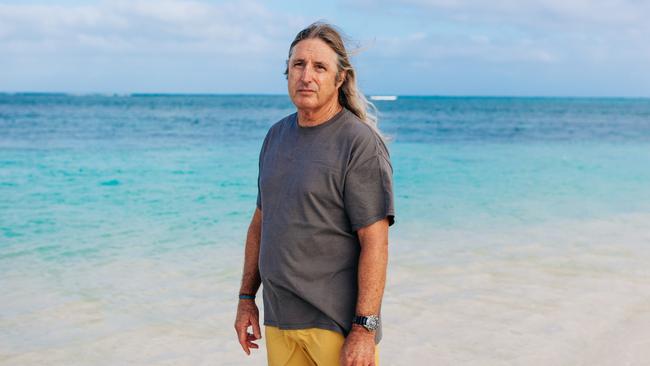

Tim Winton on Ningaloo, his new ABC documentary and ‘sensitivity readers’

Novelist Tim Winton reflects on ‘sensitivity readers’, his beloved Ningaloo and stepping in front of the camera for the first time.

You spent quite a bit of time last year picking parasites off the lips of whale sharks. How did that happen, Tim? I first came into contact with the whale sharks at Ningaloo (a Unesco World Heritage site off the coast of WA) 30 years ago. Some friends lured me out onto the water with the idea that we might go fishing, then said, “You’re going in.” I went over the side in my undies, with a mask and snorkel, and a pair of fins. Out of this purple gloom came this enormous thing, like a slow-moving submarine. A whale shark. The biggest fish in the world. Amazing.

Could you feel its presence in the water? Like if you’re standing on the edge of the highway and a road train goes by? No, it isn’t quite the same, but you definitely feel the movement of the water around you.

So the task you had picking parasites off its lips, that was for science...? Yep. They’re called copepods. To get them off, you have to get in front of the fish, so it’s like hanging off the front of a bus. You’re swimming backwards and you can see into its mouth, which is the size of a bathroom. Sometimes it changes angle, it goes almost vertical, pushing you up until you break the surface, while it hangs down, and as long as you keep picking its lips, it will stay like that.

Besides exploring the reef, you accompany traditional owners back to rock shelters, where the famed Mandu Mandu beads – 32,000-year-old ornamental artefacts – were found. Your companions weep as they return to their ancestral lands; were you close to weeping yourself? I was first approached in 2018 to make this show, and the traditional owners only got native title over Ningaloo in 2019. So it’s that fresh, the idea that they can go back there, as custodians. I love Ningaloo, I defend it as kin, it’s that serious to me, but my connection to the place is ephemeral compared to somebody whose people go back probably 60,000 years. There were people at Ningaloo when there were Neanderthals in Europe, and they’ve been told over centuries that their families never existed. It’s mind-blowing.

Writing is a solitary endeavour. Did you enjoy the process of working collaboratively with filmmakers? You’re right: I have spent 40 years as a sole trader, a solo operator. The entirety of my working life has been spent in a room on my own with people who don’t exist. I’d never written a natural history TV series. I didn’t know what I was doing, and I had just put my hand up at every possible juncture to say, “I don’t know what I’m doing here, can somebody help?” I learnt a lot.

You’re the host, as well as the writer. Are you comfortable in front of the camera? No. I just felt like I had to do it. And I did it despite my discomfort and you know, obvious incompetence.

You’re doing well until you get whacked in the shallows by a Bottlenosed Wedgefish – which seemed well within its rights, given it was about to have a tracker surgically inserted. He was within his rights. And it hurt. And my nose got damaged, and I ended up on my back, and then my nose got infected. Nature fights back. You have to admire that.

The documentary makes plain the beauty of this remote part of Australia. Are you worried that too many people will now want to see it? It’s a balance. If the Juukan Gorge had been famous, Rio Tinto wouldn’t have been able to blow it up. If people know about something, then they’re more likely to value it. It’s remote, it’s hard to get to. We wouldn’t want anyone to think they can get away with doing something to it, because nobody knows it’s there.

You’ve been campaigning for Ningaloo for more than 20years. Some of the guys protesting with you in the early 2000s seem to have gone a bit corporate, cut off their ponytails. Not you? No. Those of us who are basically ancient landforms, we just stay the same. You know, I didn’t think I was young when we were out there marching 20 years ago. I thought I was already an overweight sun-damaged, middle-aged man. Now I’m even older, overweight, sun-damaged man.

You seek greater protection of the natural environment from mining – but mining is essential to the health of the Australian economy. Must we strike a balance? There’s no question that we, in order to survive, must consume. All of us have an impact. But we get to make political choices about the places that that we surrender to our appetites, and those that we protect with our restraint. It’s too late for the Pilbara. Let it not be too late for Ningaloo.

You were locked down in WA during Covid. Did you find yourself more or less creative?I’m not sure it made a difference. The time to write a symphony, or a novel, is not time that’s granted or gifted to you. It’s time you commit. I don’t think lockdowns helped anyone – I mean, lots of people started ukulele lessons, but how many still play?

To some current debates in literature: can you write any character you want, or must a writer now “stay in their lane”? You can write anything that you like. You just have to brace yourself for people’s response to it. But that’s always been the case. You’re at the mercy of readers. I don’t think anything’s changed in that sense.

Should the classics, in particular children’s classics, be reviewed by “sensitivity readers”, as has happened with Roald Dahl and Enid Blyton? I think we need to trust people to make up their own minds up about whether something is appropriate or not, for themselves or the kids. I think that most people are sophisticated enough to understand that language changes over time. Readers are also entitled to exercise agency.

How would you feel if somebody excised, say, depictions of sexual assault or violence from your novels, on the basis that readers might find them distressing? It seems like violence, or depictions of suffering have always been distressing to read. But that’s not a reason not to read them.

Thomas Keneally has said that he wouldn’t write The Chant of Jimmy Blacksmith today, at least not from the perspective of an Indigenous Australian. Did you overreach with any of your characters? Whenever you sit down to do something you’re at the mercy of your limitations, including experience, at that time. So in that sense, all your books appear to you as a litany of failures, and if you had nothing else to do, I suppose you could go back and tidy them all up, but I’m sure there are many people who want to go back and tidy up their adolescence, or tidy up their childhood, or tidy up parts of their lives, and it’s just not possible. You have to keep going forward; you know, sharks don’t swim backwards.

Ningaloo Nyinggulu, a three-part documentary written and presented by the four-time winner of the Miles Franklin Prize for Literature, Tim Winton, will air on ABC TV from May 16.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout