‘They’d never heard of modern dance … but I couldn’t live without it’

She pioneered modern dance in Australia and now the company she founded in the 1960s has brought the legendary performer back to centre stage.

It’s a beautiful spring afternoon and I am headed to a magical part of the world to meet two Australians whose lives and life’s work are intricately woven into the nation’s cultural fabric. Built on the foreshore of the vast and full Lake George, 40km outside Canberra, Mirramu Creative Arts Centre is both the home and workplace of Elizabeth Cameron Dalman OAM. “Liz”, to all who know her, is the founder of modern dance in Australia – respected, revered and still active as a dancer and dancemaker today, aged 90. Daniel Riley is her protégé of sorts, a vibrant young Wiradjuri man who now runs Australian Dance Theatre, the nation’s oldest continuing contemporary dance company and the organisation Dalman founded 59 years ago in Adelaide. Riley, 38, owes his life in dance, his discovery of his people, his cultural awareness, to Dalman. And it is time to share their story.

But first there is the small matter of the sheep. Interrupting the serenity of this cloudless day, with bright parrots feeding on the cherry blossoms and the wattle exploding, is neighbour Shaun’s herd of ewes and lambs, which have somehow escaped and are now gambolling cheerfully along the dirt road towards Dalman’s 40ha property, eyeing the mountain behind Mirramu and the certain freedom that awaits. Shaun roars up on his motorbike in the nick of time, and a crisis is averted.

Standing quietly observing the scene with a wry smile is Dalman. She’s a picture of elegance in an arresting purple dress and flowing black pants, a jade turtle pendant around her neck and silvery hair swept back. Her presence is calm and powerful. She greets me like an old friend, and warmly welcomes me to Mirramu. Next to arrive is Riley, who has driven from Sydney, having flown in from Adelaide the night before. The pair hug and the three of us make our way inside Dalman’s mud brick home, where a generous spread of veggie bake, warm pumpkin soup and a smorgasbord of meats, salad, bread, cheeses and wine awaits us.

As we settle in for the afternoon I’m taken back to Adelaide in 1965. Dalman, then a young firebrand just back from Europe, her mind and body bursting with avant-garde ideas about dance and culture, arrived in the conservative city determined to shake things up. She would be labelled a “communist rebel” for her efforts, but nothing would dissuade her from her calling: to create an Australian voice in contemporary dance. Not then, not now.

“When I was three someone said to me, ‘What do you want to do, dear, when you grow up?’” she recalls.

“I. Am. A. Dancer,” the young Elizabeth replied emphatically.

“I feel very grateful I have always known. It’s been a hard, hard road but it’s what I’m here to do,” she says today.

Dalman was born in 1934, a descendant of two well-known Adelaide families, the Bonythons and Cameron Wilsons, whose members have included premiers, politicians and judges. Although there were writers and visual artists among them, none were performing artists and Dalman has reflected on feeling “a little like the black sheep”. That determined three-year-old began dancing with Nora Stewart, learning classical ballet and, unusually for the times, the techniques of modern English dancer Margaret Morris. It was an early introduction to a radical style that saw Dalman dancing in bare feet and short tunics, a far cry from ballet slippers and leotards. She continued learning until 21, when she quit her university arts degree for Europe and a career in dance.

She studied classical ballet in London but it was a performance of modern dance by José Limón and his company at Sadler’s Wells in 1957 that blew her mind, leading her to work for three years with the young African-American modern dancer Eleo Pomare, who would become one of the most influential figures of her life. She performed across Europe, and in New York, often in unconventional theatre spaces such as galleries and parklands.

“I was living in Europe, dancing in a small dance company in Holland – all foreigners pioneering modern dance. It was an amazing experience, we lived like a family,” she says.

It was here that she fell in love with Dutch photographer Jan Dalman. They married and travelled to Australia in 1963 so she could show her country to her new husband, who, drawn to Adelaide, decided they should live there.

“I thought, ‘OK, I’ve had an amazing experience. Now I’m going to be a wife, I’m going to learn about photography and hopefully be a good mum’,” Dalman says with a smile. “But I found I couldn’t live without my dance.”

Dalman determined she would become a teacher of modern dance techniques espoused by the likes of Limón and Martha Graham, alongside jazz and African dance. But after visiting multiple ballet schools, every door slammed in her face – with one exception: that of former London Royal Ballet soloist Leslie White, who welcomed her in.

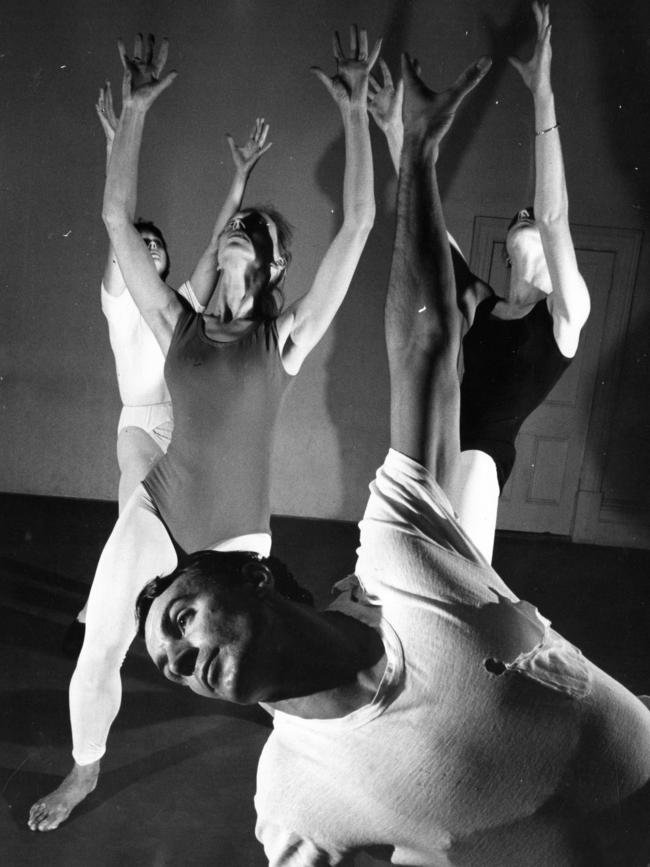

The following year, on June 10, 1965, the pair established Australian Dance Theatre (ADT) in a studio in Gay’s Arcade, teaching and performing modern and classical works. When White departed for Brisbane in 1967, Dalman decided to focus exclusively on modern dance. While Gertrud Bodenwieser and Margaret Barr ran modern dance groups in Sydney, and Shirley McKechnie did likewise in Melbourne, ADT was the nation’s first professional modern dance ensemble.

The name was selected carefully and deliberately. “[The word] ‘Australian’ was the big question mark, because we were suffering cultural cringe and anything Australian, particularly in the arts, was not good enough,” says Dalman, noting her later requests for ADT to be included in the Adelaide Festival were repeatedly refused. “‘We don’t have locals’,” she recalls being told, “‘we only have companies from Europe and Great Britain and maybe America.’ I was so angry.” The word “Dance” in the name was a radical choice, as dance circa 1960s Australia equated to ballet, ballroom or folk dancing. “They’d never heard of modern dance, particularly in Adelaide, so that was revolutionary.” And “Theatre” was chosen because Dalman was watching closely what she calls the “wild things” happening in theatre at that time, with traditions being challenged through musicals such as Hair.

Not everyone was appreciative of ADT. Its style of dance was branded by one reviewer as “ugly”, while others criticised the choice of bare feet and a lack of physical conformity among the dancers. Australian Ballet artistic director Peggy van Praagh refused to even speak with Dalman, although her male dancers would regularly sneak in to class with ADT when touring Adelaide. “The boys used to knock on the door of the studio because they wanted to do class but they’d say, ‘Liz,’ [she drops her voice to a whisper], ‘you mustn’t say anything because Peggy will dismiss us’.” It was sweet revenge, then, when Dalman visited Sydney Opera House last year to watch The Hum, the Australian Ballet’s co-production with ADT, choreographed by Riley. “I wonder what Peggy would have had to say,” she says with delight.

While South Australia was a conservative state under 26 years of Liberal government, things were about to change. In 1967 Don Dunstan swept to power and so began the state’s transformation. Not only did the Dunstan era usher in Indigenous land rights, the decriminalisation of homosexuality and health and education reform, he oversaw an unprecedented investment in the arts. The State Theatre Company, the SA Film Corporation and New Opera South Australia (later renamed the State Opera of South Australia) were just some of the cultural milestones Dunstan achieved.

It was in this climate that ADT began to flourish, with Dalman’s works reflecting the voice of her generation and the social and political climate of the time – the anti-Vietnam War movement, an emerging national identity independent of Britain, women’s liberation and Indigenous rights. Dalman responded to the new proudly Australian artistic voice, too, commissioning scores from Australian composers Peter Sculthorpe and Richard Meale, performed alongside music by Bach, Ravel or Peter, Paul and Mary.

Audiences responded, and regional and interstate tours were soon expanding to tours of Europe, Asia and New Zealand, supported by generous government funding. By 1975 ADT had presented more than 100 works, 35 of them choreographed by Dalman.

But that same generous government was also responsible for unceremoniously dismissing Dalman and her entire company in 1975 after the Australia Council, the federal government’s arts funding body, made funding conditional on the company being run by a board appointed by the funding bodies. That board made the bewildering decision to get rid of the dancers and Dalman, who maintains there was no consultation or forewarning.

Writing in Fifty: Half a Century of Australian Dance Theatre (2016), former Adelaide Festival director Robyn Archer notes: “Whatever the rationale of the board for terminating their contracts, the way it was done was devastating to [Dalman] and the company. Unhappily, it set a precedent of poorly managed dismissals that has until recently dogged the company.”

ADT has had only five artistic directors since, each one with their own distinct voice and style; almost all were unceremoniously ousted. Former Ballet Rambert dancer and choreographer Jonathan Taylor (1977-85) succeeded Dalman, introducing audiences to British choreographer Christopher Bruce and creating his landmark production Wildstars. Former Nederlands Dans Theater dancer Leigh Warren (1987-93) brought in acclaimed American choreographer William Forsythe to collaborate with ADT, while inviting local choreographers Graeme Murphy and Kate Champion to create works on the company.

Pina Bausch-trained dancer-choreographer Meryl Tankard (1993-99) brought an exciting new dance language to the local scene through works such as Furioso, lapped up by audiences in Australia and abroad; and Garry Stewart oversaw boundary-pushing collaborations in the fields of robotics, architecture and photography, while creating a distinct and thrilling new movement style. Stewart chose his own departure date, in 2021, following an undeniably successful era during which the company was constantly in demand abroad and interstate.

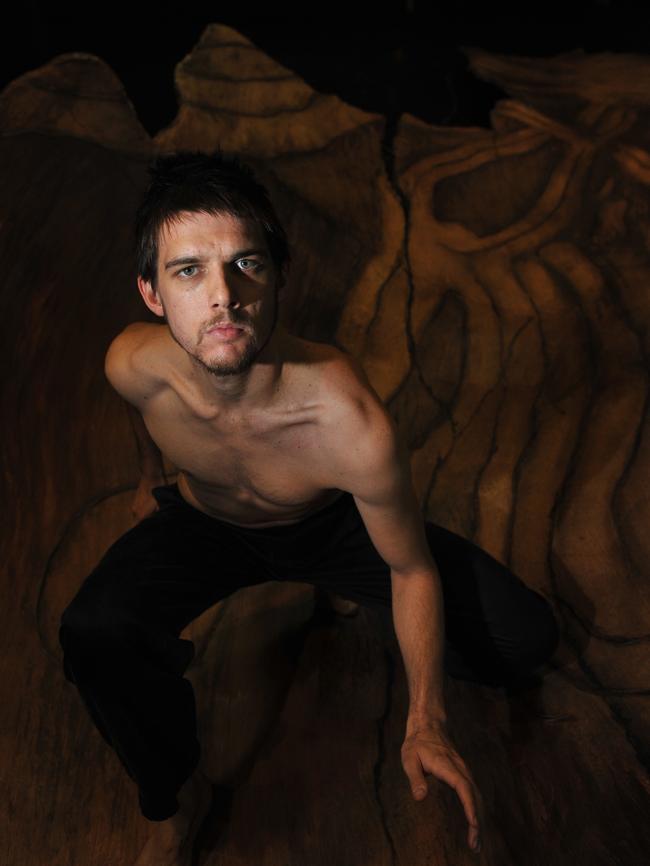

When Daniel Riley began fielding calls alerting him to Stewart’s impending departure and encouraging him to throw his hat in the ring, he didn’t think he stood a chance. After all, his vision would be for a vastly different ADT. And significantly, there was no precedent for a First Nations director running a non-Indigenous dance company. How wrong he was.

Professional dancers are a unique and rare beast. Few of us would choose to put our bodies through the punishing physical and mental regime that dance demands from a young age until your early thirties (if you’re lucky), when the strength and stamina required are simply no longer possible. Dance is a vocation, not a profession. It was no different for Riley, although it took the guidance of Dalman to lead him there.

Riley began tap-dancing when he was nine, living on Sydney’s Northern Beaches. When the family moved to Canberra he pestered his parents to find him a new dance school. His primary school teacher father consulted his colleague, Dalman. She immediately directed him to Quantum Leap (now QL2), a new youth dance group that was part of the nearby Australian Choreographic Centre.

“I started the classes at Quantum Leap in 1999 and instantly felt I’d found something. It was transformative. I felt like I’d found my people,” says Riley. “So that was my first interaction with Liz.”

Riley would go on to have two more life-altering epiphanies. The first was when ADT toured Birdbrain, Stewart’s radical deconstruction of Swan Lake, to Canberra in 2001. “It blew my mind. The vibrancy of it, not knowing anything about contemporary dance and what that was. I remember thinking, ‘Wow, I could do that for a career?’ I could never have imagined I’d be leading the company one day.”

The second was when the nation’s leading Indigenous dance theatre company, Bangarra, toured The Dreaming to Canberra. Having only learnt through his father of his First Nations background while in primary school, Riley was desperate to learn more. “That performance blew my chest wide open, thinking, ‘Whoa, there are people up on stage connecting with their culture who look like me.’ That was pretty extraordinary. And from that point I knew: ‘I want to be a dancer’.”

After graduating from Queensland University of Technology in 2006 Riley joined Bangarra, and remained with the company as a senior-dancer-turned-choreographer until 2018; the experience expanded his dance vocabulary and gave him a precious understanding of Indigenous culture through visits on country and discussions with Elders.

Throughout it all Dalman was quietly in the background.

“Liz would always be there on opening night of Bangarra [in Canberra], whether I was performing or had made a work,” says Riley. “Whether I was at a show or visiting family, we’d run into each other and there was always a connection, a warmth and a familiarity.”

Dalman has kept a watchful eye on Riley throughout his career. “I wanted to know how Daniel was going, and when he started making choreography I was fascinated and would try to follow him. His mother-grandmother was keeping watch,” she says with a chuckle.

In many ways Riley’s life was leading to the point at which he would take over what Dalman had started, becoming the sixth artistic director of ADT. Having worked with Rachael Maza at the First Nations theatre company Ilbijerri in Melbourne, where he undertook an executive leadership program, Riley went on to create works for companies ranging from Louisville Ballet to Townsville’s Dancenorth, and joined the board of Melbourne’s Chunky Move contemporary dance company, led by ADT alumnus Antony Hamilton.

Riley was lecturing at the Victorian College of the Arts and living in Melbourne with wife Chrissy and son Archie (daughter Billie has since joined the family) when the calls about the ADT role began flowing in, from mentors and friends including former European development manager for the Australia Council Sophie Travers, who told him to write down his vision for ADT and see what it looked like.

“I wrote it down and it seemed like a wild idea that ADT would be led by a First Nations artistic director. But I thought, ‘If not now, when?’ and I felt really strongly about the vision I had for the company. And if the ADT board weren’t going to get behind it, I’d go somewhere else.”

Get behind it they did, and in January 2022 Riley took over and began quietly and collaboratively working on his vision to return this globetrotting dance company to Adelaide and South Australia, first and foremost, performing works by and for Australians.

“I had no idea who would be the next artistic director until Daniel phoned me up. I was blown away, I thought it was so marvellous,” Dalman says. “Here was this young, really good choreographer, a great performer who has enormous stage presence. And that he was First Nations, because one of our missions in early ADT was to be a voice for First Nations. We were searching in the ’60s and ’70s for our identity, as Australians.”

Next year ADT will celebrate its 60th anniversary. Gearing up to celebrate this milestone, Riley knew there was one person he needed to bring home: in May ADT welcomed Dalman back to the studio. Not for a day or a week, but a full month of rehearsal, consultation, conversation and collaboration. She led a number of classes with the six company dancers, delighted with the hunger they showed for her dance technique.

“I just loved it, and of course there is no age in dance, when we’re teaching and working together we’re all ageless,” the energetic nonagenarian says.

In turn Riley and the dancers have twice visited Mirramu, sleeping in the additional mud brick house Dalman uses for visiting artists, poring over her meticulously maintained archives and exploring new dance movement in Mirramu Dance Company’s studio.

“Liz and I have spent a lot of time talking about the foundations of the company; it’s critical to me we understand the works in that social, cultural and political climate in Adelaide and the nation and the world,” says Riley. He will incorporate this knowledge into his new work, A Quiet Language – centrepiece of ADT’s 60th anniversary celebrations and a headline act at the 2025 Adelaide Festival in February.

“Culturally for First Peoples our eldership is critical because if we don’t look upstream to where we came from, we don’t know where we’re going,” he says. “I want to honour that legacy. I understand I’m downstream of Garry Stewart, Meryl Tankard, Leigh Warren, Jonathan Taylor, Liz and all the people who have worked for ADT – over 300 dancers and 160 creatives and all the staff. We could just roll out some repertoire but I wanted to understand the ‘why’ around all the works, and it’s clear the ‘why’ hasn’t changed – it’s still about people, the body, politics, voice and place.”

As Dalman sits back, quietly taking in all Riley has to say, I ask what she makes of it – the legacy, its place in Australia’s culture today, and Riley himself.

“I created it and watched it through all the different directorships – some accepted me, others did not – but it’s always my child,” she muses. “This one feels very special because there are fundamentally strong connections to our aims – about being Australian, about dance as an expression of spirit and the social, political and cultural concerns of the day. Our First Nations voice is vital, now more than ever, so it’s important we have Daniel there right now. And he knows I support him in what he does.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout