Adventurer Huw Kingston skis 700km across the Australian alpss

In 1997, aged 34, Huw Kingston traversed the Australian Alps — 25 years later the scenery and the adventurer have changed

Mount Feathertop, perhaps the shapeliest of our alpine mountains, rose like an orca’s fin above the sea of cloud that had been beneath me all day. The sky glowed orange as the sun dived beneath the surface. The edge of the cloud lapped at the ridge I was on, occasional silent waves crossing it before rolling back. The curtains were closing on a perfect winter day. I was ascending Quartz Ridge on backcountry skis on a route leading to Mt Bogong, Victoria’s highest peak. This south-facing ridge had seen little sun all day and, as I skied up a steepening pinch, the surface was getting ever firmer. My skis were on edge; I was on edge. My gear was operating at its limit, my own skill too perhaps.

Once again I banged the metal edge of a ski into the ice. It held. I banged. It held again. And again. Then suddenly my bum hit the ice. I readied myself for a long slide down the luge run of the gully below me. But the bum somehow held. Looking down, I saw one of my skis hanging from its safety leash, having parted company with my boot and thus causing my fall. From this precarious position I had to remove both skis and drop neither, then slowly, carefully, turn to face inward, kicking small indentations into the ice for my boots – and continue kicking those tiny steps until the angle eased, and with it my worries.

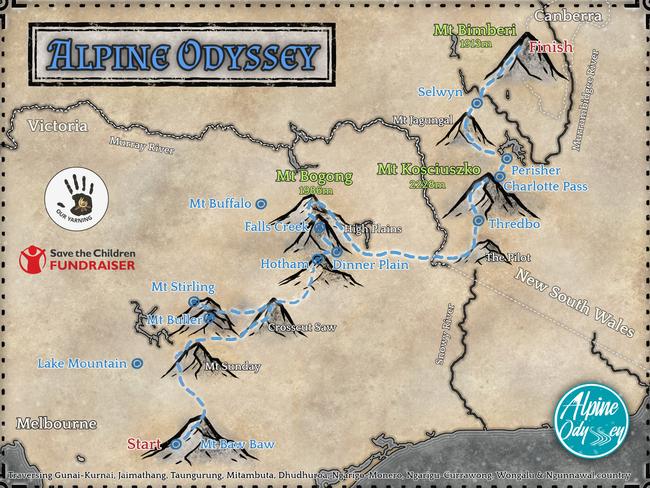

I was a month into my Alpine Odyssey, a 700km winter traverse of the Australian Alps by ski and foot. A journey from Victoria’s most southerly snow resort, Mt Baw Baw, east of Melbourne, to the long-abandoned ski resort of Mt Franklin in the mountains west of Canberra. Back in 1997, aged 34, I’d completed a similar winter traverse of the Australian Alps and I was keen to see what had changed – indeed, how I might have changed. This time, my wife Wendy and I drove from our home outside Jindabyne to the start line at Mt Baw Baw in a Hyundai Ioniq electric car. We watched the battery level plummet on the steep, snowy climb to the resort. How would my own battery perform as it moved close to its seventh decade? Would my reputation as a reliable old diesel – some might say high-emission old diesel – still hold?

My odyssey, which began in late July, had an added twist. I would make regular diversions in order to ski at the dozen snow resorts dotted across our alpine country. I have loved these places for decades, and have had many treasured experiences there – from endless descents on the pistes to “earning my turns” out in the backcountry, living it up in lodges or camped high out on the range. But with love comes concern. In recent decades our alpine country and communities have faced new threats: bushfires and climate change, feral fauna and flora – and, in places, perhaps even suffocation from the many visitors who seek to enjoy the mountains’ charms and challenges.

Consider, for instance, Mt Bogong. For thousands of years before I carved turns down its flanks or held onto my tent in wild blizzards, our First Nations people gathered there in summer in great corroborees, to trade, share stories and feast upon the protein-rich Bogong moths that smothered the mountain, which they call Warkwoolowler.

The Bogong moth is rarely seen now. How long since these insects banged on the windows of my Snowy Mountains home? How long since lights were turned off at Parliament House in Canberra in an effort to lessen their suicidal tendencies?

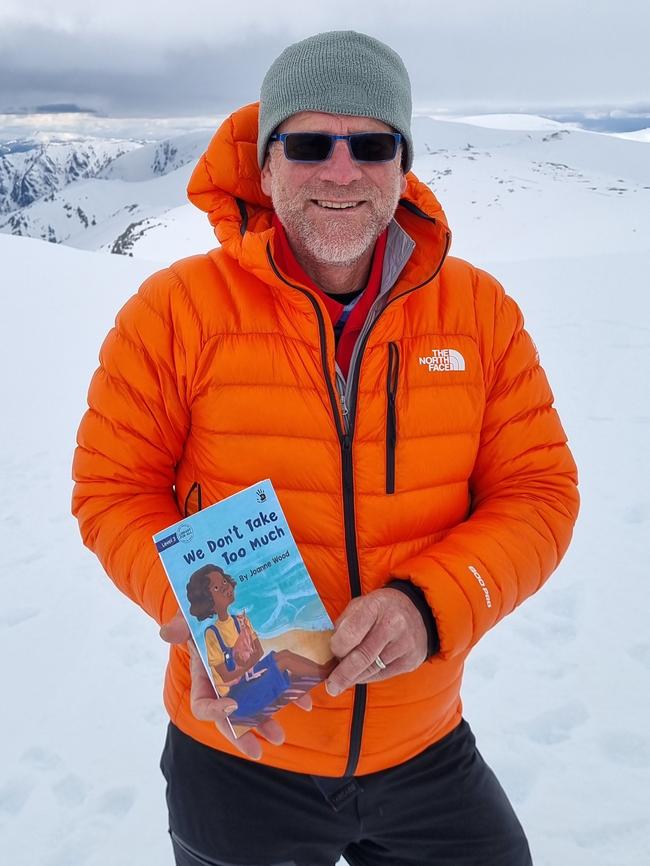

Taungurung elder Uncle Shane performed a smoking ceremony and a Welcome to Country for me at Lake Mountain, a resort near Melbourne where I enjoyed a ski before starting my journey proper. He offered strength for the undoubted challenges ahead. We discussed everything from the regathering of stories in the Alpine country (my odyssey would raise funds for Our Yarning, a literacy project producing books for Indigenous Australian children), the links these stories have to mobs as far away as the Central Deserts, and the endless uses of a possum cloak.

At Mt Baw Baw I shouldered my pack, heavy with gear and food, and set off on a grey, blustery morning. In the wild wind, snowgums threw down strips of bark, like some too-soon ticker-tape parade. It was a long way to the finish line.

I knew those first weeks would be the toughest. Good initial skiing conditions were made marginal by heavy rain and unseasonably warm temperatures. Too often my skis were more crucifix on my back, not transport beneath my feet. I’d seen first-hand, in 35 years of winter wanderings in the alps, that the snowline was rising. Country that had been regularly snow-covered now stays green; rivers that once flowed fast only with the snowmelt of spring now often flow fast all winter. The records this past half-century confirm the trend. In the alps, where winter temperatures hover close to one side or the other of zero, a small change means the difference between freeze and thaw, snow and rain.

In the first couple of weeks of my journey, at lower altitudes, thick bush did all it could to entangle my skis, and on numerous occasions I resorted to pushing forwards on hands and knees. The names on the map – Son of a Bitch, Mt Buggery, Mt Despair, The Terrible Hollow, Horrible Gap, The Razor – showed I was not the first to feel frustration in crossing this country.

On one particularly wet day, about a week after setting out from Mt Baw Baw, I came to the swollen Black River. A slippery, fallen tree trunk offered a way across. If I’d thought too long about crossing it, I’m sure I would have baulked; as it was, inching across the log, legs shaking, I wish I had. On all my long journeys over the years, it’s rivers that have most often caught me out. It’s easy to underestimate the power of their flow, easy to be foolish. During my 1997 traverse of the alps, while crossing a swollen Big River, I’d nearly drowned.

Adding to the challenge on this current trip, I’d broken a rib during one particular after-dark bush battle when I’d lost a thin track. But I pushed hard on very long days, dawn until dark, keen to get across the infamous Crosscut Saw – two weeks into my journey – before a forecast blizzard hit. The Crosscut Saw is a series of rocky pinnacles joined by a very narrow ridge and is, undoubtedly, the most challenging winter ridge traverse in the Australian Alps. Narrow, exposed in parts, it required some tricky, delicate manoeuvres.

Strangely, from the point where I’d gained enough elevation to be constantly on snow again – along King Billy, over Mt Howitt, right along the Crosscut Saw and on to Mt Speculation – fresh paw prints, dingo or wild dog, led me on.

While a dog had trodden the same path as me in the wilderness, it was a god who skied with me when I reached the civilisation of Mt Buller resort; a Hindu sect, celebrating the centenary of its guru’s birth, had taken icons to the snow (as well as to Uluru, the Opera House and the Barrier Reef). Somehow, I found myself skiing down a piste nursing a gilded statuette in my arms.

Coming into resorts like this from time to time offered comfort and contrast. A soft bed in a warm room is so different to a sleeping mat in a wet tent; twisting a tap for water much quicker than melting snow on a little stove. A cold beer more enjoyable than frozen hands. I was well looked after, none more so than by The Astra in Falls Creek where Alpine Odyssey fundraising cocktails were on offer and a barber’s chair tamed my locks, a massage table my leg muscles.

My arrival in Falls also coincided with the Kangaroo Hoppet. Attracting 1000 skiers, the Hoppet is Australia’s largest cross-country ski race. Using lightweight racing skis, the 40km was the furthest I’d travelled in one day on my journey, and in the shortest time, 2.5 hours – only to end up back where I started. (And true to its name, Falls also gave me the biggest tumble of my journey: on a downhill section in the race, I lost control on a sharp corner.) After two seasons wrecked by the pandemic, it was good to see the resorts cranking again, the slopes alive with the laughter of skiers and boarders. For me it was a chance to ski with old friends and new acquaintances.

Back into lower country after linking the eight Victorian snow resorts, I pushed on towards Thredbo, the first of four resorts in NSW. In the first days of spring, I sprung from one state to another across the metre-wide Murray River, just starting out on its 2500km journey to the sea.

At Thredbo it was so good to see Wendy again, the first time since Mt Baw Baw. I bid farewell to photographer Mark Watson, who’d accompanied me since Mt Bogong, then I enjoyed some thigh-burning descents on the slopes before leaving to ski to the summit of Mt Kosciuszko, the highest peak in mainland Australia at 2228m. From here I could gaze north across the Main Range and way beyond to isolated Mt Jagungal. Up here the snow depths held up well – the mountains were plastered in the white powder so many of us are addicted to, thick cornices rolling off the lee side of the mountains.

My camp that night looked across to Watsons Crags, a place offering some of Australia’s steepest backcountry terrain. My thoughts were with the family of a young backcountry skier who’d lost his life there just two days before. Such incidents touch all of us who love skiing and boarding beyond the resorts. There is a thin line that we traverse with a mix of skill, experience, weather, snow conditions and luck. Occasionally it plays out the wrong way; very occasionally, in tragedy.

Then I struck out across the infant Snowy River to Charlotte Pass. In 1986, as a British backpacker fresh out of university, I found myself working a season at this little resort. It was where I learnt to ski and where my passion for our alpine country began. It’s where I first fell in love, too, with the symphony of the snow: the muffled gurgle of a creek flowing beneath the snowpack, the dawn roar of the stove brewing the first coffee of the day, the sleepless torture of tent fabric flapping all night on a wild night, the satisfying click of ski boot into binding, the windless sound of nothing under a full moon, the clanking of a T-bar lift arcing around a bullwheel, heavy breathing behind an iced-up neck warmer, the groan when lifting a heavy pack onto aching shoulders, the squeal of a pair of rosellas flashing past a mountain ash, the whoops of joy linking turns down a virgin slope, the tinkling of rime ice on a snowgum.

From Guthega, a part of Perisher, my penultimate resort, I headed across the Rolling Grounds in foul conditions of blizzard and whiteout, where it became impossible to discern ground from sky. But such foul conditions, of course, mean fresh snow – and without snow there are no snowsports. So, regardless of discomfort, I’d never complain.

Just on dark, soaked through and cold, I dropped down to an old stockman’s hut and had the good fortune to find find three Brazilians inside with a fire roaring. Covid visa extensions had allowed Carlos, Felipe and Paulo to stay on in Australia, and they too had fallen quickly for the charms of our high country.

On the eastern flank of Mt Jagungal I removed my skis for the last time, coincidental to entering country burnt in those fiery summer months three years ago. Then, as the sun lowered late one afternoon, I witnessed renewal in the form of Selwyn Snow Resort: brand new ski lifts, buildings and more, risen from the ashes of its total destruction by those fires. I had skied at all 11 of the resorts I’d visited so far but, as I approached Selwyn, it seemed trite to seek out a little patch of snow just to say I’d skied there. Far better to enjoy my turns under a blanket of snow, with lifts cranking and people enjoying it. Far better to wait until the winter of 2023 to celebrate Selwyn’s reopening.

But standing in mid-September on those bare slopes, I did have to wonder about the rebuilding of a resort that sits low in altitude and further north than any other in Australia. Unless we can turn the tide, can any amount of snowmaking technology really outpace the rising temperatures?

I continued into the last days of my journey, on through the northern reaches of Kosciuszko National Park, on toward the ACT. Blackened trees gave way to green ones. I stopped, mesmerised, as a lyrebird mimicked a rollcall of the birds I’d seen those past 50 days – currawongs, rosellas, kookaburras, ravens. And at the Murrumbidgee River I stared long and hard at the deep, fast flowing water. It was probably OK to get across. Probably. But that’s the issue with river crossings, like a siren they entice you in. It was too close to the end of my journey to risk it; surely much better to take the 2.5-hour detour. I turned away, walked away. Then, hesitating, turned back to the river. Then away.

On those last days in the NSW alps, the trails were awash in the faeces of feral horses. Entering Wongalu and Ngunnawal Country, I walked in fresh snow across Murrays Gap and into the ACT; here, in Namadgi National Park, the mountains of poo disappeared, no horses seen, the result of a successful control program that side of the border.

There was one final camp, my first and last in the ACT, before a day through the snow to Mt Franklin and a finish on the footprint of the old Canberra Ski Club chalet that had stood there. Our alpine country had more than nourished me again.

In 1997 I didn’t see or speak to another soul for the first 18 days. Finally, arriving at a snow clearing depot below Mt Hotham late one night, I’d dropped in to use the phone. Classical music was playing and the road crew were glued to the TV. “If you haven’t seen anyone you wouldn’t know about Princess Diana,” said one burly bloke, can of VB in hand. “That’s her funeral we’re watching.” A quarter of a century on, and the day after I finished my journey, the world was tuned into the burial of her mother-in-law, the Queen. Soon afterwards my own mother-in-law Eira, whose name means snow in Welsh, passed away. I can only hope that in another quarter of a century we will still be celebrating, not lamenting, the winter wonders of our highest country.

Huw Kingston would like to thank The North Face and the people and resorts of the alpine country for all their support. Details on the Our Yarning project can be found here.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout