The race to save the world’s largest flower from extinction

Rafflesia is a botanical enigma — a bright-red parasitic colossus that reeks of rotting flesh – and it’s disappearing before our eyes.

The air is sticky sweet and raucous with cicadas as Joni Hartono veers abruptly off a narrow mountain track and into the tangled green of West Sumatra’s Palupuh Nature Reserve. The self-styled guardian of one of the world’s great botanical enigmas flaps confidently in sandals up steep muddy slopes, pointing out an extravagant sideshow of wild treasures – pitcher plants, orchids, mimosa, wild nutmeg – as he forges on to the main event.

For more than two centuries, scientists, amateur naturalists and intrepid travellers have crossed continents to reach this remote corner of Indonesia, rolling the dice that they have timed their arrival to coincide with one of its most ungovernable marvels, the flowering of the Rafflesia plant – only for many of those odysseys to end in gutting disappointment.

The startling red and white behemoth is like the black rhino of the flowering plant world – rarely sighted, critically endangered and endemic to a few remote pockets of the planet.

As the largest flower on Earth, it should be an icon of tropical conservation. Instead, it is a dodo in the making.

Already vanishingly rare, two-thirds of the 42 known Rafflesia species now exist in unprotected habitats – in Indonesia, the Philippines and Malaysian Borneo – that are rapidly disappearing to make way for cash crops.

But in this protected patch of Sumatran jungle, one has just bloomed – and we are in a race to see it.

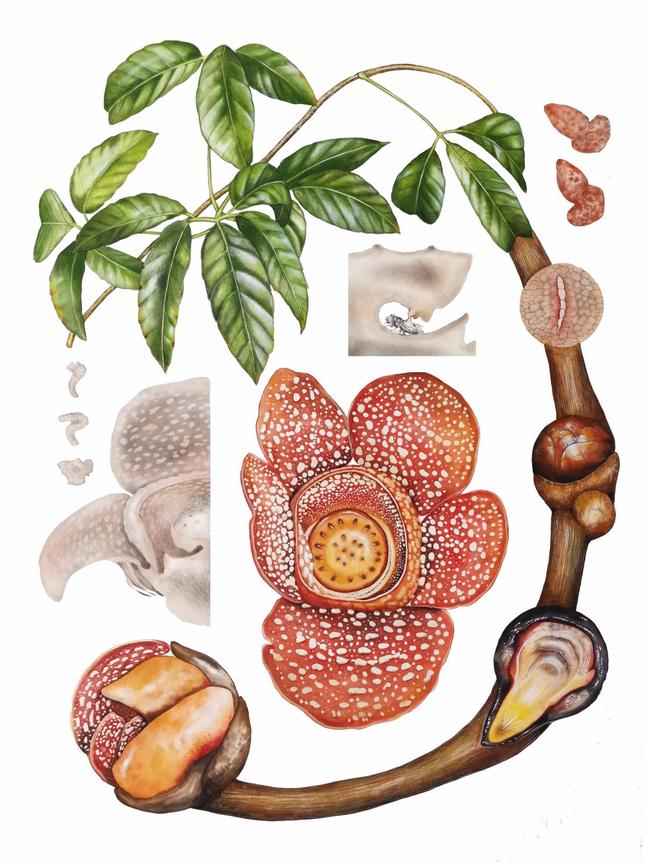

Rafflesia is a parasitic plant with a very unusual life-cycle: itspends most of its life as a microscopic thread of cells hidden inside a host Tetrastigma vine. Technically speaking, Rafflesia is an “endophytic holoparasite” – a plant that lives wholly within another plant and does not use photosynthesis; it’s one of only four such examples in the plant kingdom, and the three others are completely unrelated.

It can be years before a tight cabbage-like Rafflesia bud bursts from the vine, and then up to nine months before it blooms into a remarkable starfish a metre or more in diameter, with no stems, roots or leaves. Many Rafflesia will never make it to flower – and if they do, the remarkable blooms wilt and die in as little as five days. One host vine may never produce a second flower. Or it may produce a bud annually for a few years, then never again. And Rafflesia has been successfully grown in only one botanic garden.

In other words, all the odds are stacked against finding one.

From the capital, Jakarta, it’s a full day’s journey to the Palupuh Nature Reserve – by air, by road and then on foot – and it is only as we are climbing the jungle slopes that we learn this particular forest is home to more than one rare species. A few weeks earlier, a Sumatran tiger killed a village dog here.

Hati hati (be careful), we are advised.

The Rafflesia is an official state flower of Indonesia, of Sabah state in Malaysian Borneo (where it has long believed to have fertility properties), and Surat Thani Province in Thailand – yet its iconic status has not saved it from the ravages of deforestation. “It is clear populations of Rafflesia are being lost at quite an alarming rate through land conversion for the usual things, mostly coffee and palm oil,” says Dr Chris Thorogood, Head of Science at Oxford University’s Botanic Garden and Arboretum and a world expert in parasitic plants.

More than 10.5 million hectares of primary forest has been cleared on the Indonesian island of Sumatra in the past two decades, imperilling some of its most iconic and endemic wildlife: the Sumatran rhino, tiger and elephant, the orang-utan and the siamang gibbon. But little is heard about the loss of plant species.

“We don’t think of plants as living beings in the same way we do animals,” says Thorogood. “When people think of conservation they never think of plants, but Rafflesia could be just as powerful a symbol as any animal you can think of. We just need to learn to value them more.”

The English botanist, author of Pathless Forest: the Quest to Save the World’s Largest Flowers, is one of a handful of so-called “Rafflesiologists” – scientists who study the remarkable flower and are working with local communities to save it from extinction.

For thousands of years indigenous communities across Southeast Asia harvested the flower’s buds to reduce post-childbirth bleeding, and to promote virility. In Thailand, some believe it can bestow the power of invulnerability, others that the flower first emerged to cushion the feet of the Buddha at birth.

Each Rafflesia species is endemic to where it is found, unique to one tiny dot on the planet. Only Rafflesia arnoldii is found in a broader distribution – and even then just on the islands of Sumatra and Borneo.

Last September, the scientist group authored a study warning all 42 known species of Rafflesia were under threat. It advised that 25 should be classified as critically endangered, another 15 as endangered and two as vulnerable.

That has not yet happened. “It’s woefully bad. You think about the attention given to big animals and we have the world’s largest flower very much in peril,” Thorogood told The Weekend Australian Magazine as he prepared to trek up Mount Makiling on the Philippines’ Luzon island to check on a potentially groundbreaking experiment: the first attempt outside Indonesia to propagate Rafflesia by grafting an infected Tetrastigma vine onto an uninfected one. The experiment is now under armed guard as Thorogood and a team of University of Philippines scientists wait to see whether or not it has been successful.

The vine was grafted in March last year but it will be at least another two years before they can expect to see the first evidence of flower buds. And as with everything to do with Rafflesia, there are no guarantees.

The only place in the world where the flower has been successfully propagated through to flowering is in the Bogor Botanic Gardens, a wonderland of tropical plant species 90 minutes south of Jakarta. Thorogood spent months with its former chief botanists, Sofi Mursidawati and Ngatari, learning how to propagate Rafflesia before taking that knowledge to the Philippines, the centre of Rafflesia diversity and also where the flower is most at risk.

“Obviously it’s a parasite that grows inside its host so we know very little about its biology,” he says, likening it to a tapeworm that sends out ‘sinkers’ to absorb food. “It’s really difficult to grow. Most rare plants you might grow inside a botanic gardens to conserve it, but Rafflesia is at particular risk because you can’t bank the seed to safeguard its existence.”

To get seed, you must have a male flower and a female flower, and the odds of finding both at the same time in proximity to each other are remote, because Rafflesia are so rare, and they flower so erratically. The only realistic way to propagate the plant therefore is to graft it, and success on Mount Makiling would be a “radical advance in our efforts to conserve the plant”, says Thorogood. “It would be radical, full stop.”

Ngatari and Sofi Mursidawati’s success in propagating the Rafflesia flower in the Bogor Botanic Gardens should be a triumph for Indonesian science. The plant’s ecosystem is notoriously difficult to replicate and everything must go right, from successfully mimicking its microclimate to the way it interacts with its host.

“This is what is hardest to replicate. Rafflesia is a parasite, and usually parasites are small. But Rafflesia, strangely, is gigantic so it’s uncomfortable for its host,” says Mursidawati. It has to grow very slowly so as not to kill its host – and hence itself. Only certain species of fly can successfully transfer the pollen, and only at very specific times and locations. It took years to achieve and since then Mursidawati has propagated more than a dozen flowers including one of the rarest, Rafflesia patma.

But like so many such successes, it has fallen victim to a bureaucracy that threatens to overshadow all the good work achieved. In 2020, the Jokowi government created a new overarching National Research and Innovation Agency, BRIN, which subsumed smaller, more nimble science centres of excellence around the country and seized control of all research funding. Bogor Botanic Gardens no longer has a research capacity, and is managed by a private entity. The internationally celebrated scientists who cracked the propagation code for Rafflesia must now seek permission every time they wish to tend those flowers.

“In the past every plant in the Botanical Gardens had a botanist assigned to it. But now the researchers are outside the botanical gardens system and must seek permission. I’m only given one day a week to go there,” Mursidawati says. “There should be a botanist caring for the plants day to day.”

Indonesia has declared all Rafflesia protected species, though that alone will not save this extraordinary flower from extinction. The threats to its existence are “extremely significant” given most grow outside protected areas, “so the chance of its disappearance are quite high”, Mursidawati says. “If farmers discover it, they might sometimes conceal it because if it’s known that there is a rare plant there and the area becomes protected they won’t be able to farm there anymore. Rafflesia can only survive in its natural habitat, which is diminishing. If the habitat disappears, so does the Rafflesia.”

Some Indonesian scientists are now using satellite imagery to try to identify potential Rafflesia locations in under-explored Kalimantan (the Indonesian portion of Borneo) and the island of Sulawesi. But, admits Mursidawati, “We are racing against time.”

Eco-tourism may be the only way to conserve Rafflesia, and the buds of a cottage industry are already appearing in western Sumatra – in Palupuh Nature Reserve and also in Bengkulu, 15 hours south, where French naturalist Louis-Auguste Deschamps was the first European to document the flower in 1791. (It would take another 27 years for Rafflesia arnoldii to be named by a British expedition led by Sir Stamford Raffles, an official with the British East India Company who would go on to found Singapore, his botanist wife Sophia and naturalist Joseph Arnold.)

In Bengkulu, a group who call themselves the Rare Flower Care Community – Communitas Peduli Puspa Langka – share information on Instagram when a Rafflesia flower is blooming, and try to encourage locals to preserve them. Community chairman Sofian says so much forest has been converted to farmland in recent decades that Rafflesia is rarely found in protected areas and the group works mostly with farmers, to convince them to protect the flowers as an alternative source of income.

“We try to educate the people about Rafflesia, that it is a rare flower that needs protection, that there are existing regulations protecting it, and that it can actually bring eco-tourism for the community,” he says. “Formerly unknown villages, like Muara Sahung in Kaur Regency, have now been visited by people from many places, especially researchers from abroad.”

The good news is that villagers who might once have destroyed a newly-discovered flower to protect their farmlands are now reaching out for help – though beyond the community of enthusiastic volunteers there is little help to be found in local government, which Sofian accuses of exploiting the Rafflesia name while doing little to conserve it. Even a small farmer subsidy would go a long way towards conservation efforts, he says.

In Palupuh, Joni Hartono has spent 20 years mapping and protecting the Rafflesia flowers that occur in the forest at the edge of his village, now known as one of the most likely places to catch a glimpse of the rare plant.

He can take as many as 100 tourists (mostly Europeans; he rarely sees Australians) in the July “high season”; they will cross the globe in the hope of seeing a single flower.

“I live and work just for this flower. All the time I look for blooms,” he says as he guides us through dense forest. “Sometimes I stay overnight in the forest to protect them. No one pays me to do it.”

Talk ebbs as the jungle path grows steeper and more slippery. He stops suddenly and points ahead to a shock of distant red amid the green. A scramble down a ravine and back up the other side and we are there, hovering over an evolutionary orphan that must surely be one of the wonders of the natural world.

Like a deep sea creature, Rafflesia arnoldii’s spongy red and white petals are sprawled louchely across the rainforest floor, exposing for the briefest time a hollow heart with what looks like a giant glistening anemone within.

It is as improbable as it is magical, but two days into life it is already dying.

There is no hint yet of the rotten meat smell that has led to its unflattering sobriquet, the corpse flower – one it confusingly shares with the towering Amorphophallus titanum (or titan arum), another botanical marvel that can be seen in Sydney’s botanic gardens but, unlike the singular Rafflesia, is actually an “inflorescence”, comprised of a series of tiny flowers.

The Rafflesia at our feet will soon begin to emit that stink of rotting meat, in order to lure in pollinating insects with the “false promise of a reward to secure cross-fertilisation”. But the window of opportunity is fleeting: in four days or so the flower will be gone, perhaps never to bloom again.

“The Rafflesia is so beautiful and enigmatic, and we risk sleepwalking into a pattern of extinction,” says Thorogood, who is pushing for better protection of its habitat, more research into its biology, and greater awareness of its existence. “We will only ever protect what we care about, and what we know exists. We tend to see plants as an immobile backdrop to our lives even though we depend on them for our very existence.

“Letting Rafflesia slip over the edge into extinction is not a legacy we want to leave future generations.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout