The niche wines smashing stereotypes

It’s remarkable to think a grape so established in Australia’s party parlance – prosecco – has been with us for fewer than 20 years. But everything has to start somewhere.

Victoria’s King Valley was always going to be a good spot to start a revolution.

Hidden between granite escarpments and eucalyptus-cloaked hillsides in the state’s northeast, bushrangers would once come here to lay low, and it remains relatively off the radar, even to Victorians.

Populated with post-war Italian migrants, it’s the kind of place you visit, form a bucolic impression of sprawling vineyards and rolling hills, and then struggle later to explain exactly how you got there.

It was in one of those vineyards in 1999 that a man with the poetic name of Otto Dal Zotto planted a grape variety that grew in abundance in his home town in northeast Italy, but was virtually unknown in Australia. Five years later Dal Zotto Wines released its first vintage from the new grape, and Australian wine drinkers got their first taste of prosecco. Remarkable to think a grape so established in Australia’s party parlance has been with us for fewer than 20 years. But everything has to start somewhere.

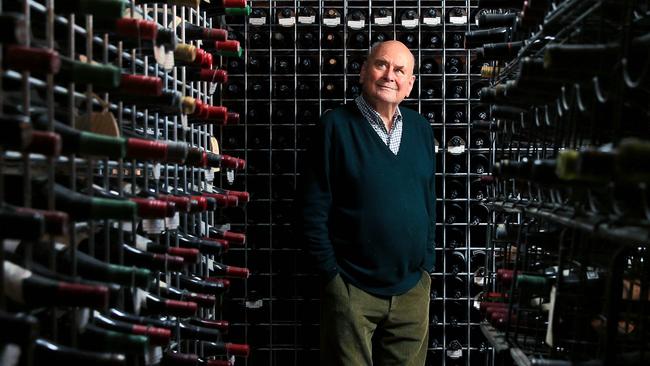

“What’s obscure now won’t be in 20 years,” says viticulturalist and winemaker Mark Walpole. He’d know. A few years before that first prosecco planting, Walpole imported to Australia 70 different varieties of Italian grapevines, selecting varieties he predicted would thrive in northeast Victoria’s Tuscan-like climate. He then watched with amusement as the large wine companies – who only had eyes for shiraz, chardonnay, cabernet sauvignon and merlot – pulled out of the region, realising the high rainfall didn’t suit the big-name grapes.

It was the beginning of a mass diversification of the Australian wine landscape.

HALLIDAY'S TOP 100

Drink like James Halliday with this offer

The Australian Wine Club is offering a mixed dozen from James Halliday’s Top 100 - including a 99-point sensation - for $27.99 a bottle. Find out more.

Australia’s top 20 champagnes and sparkling wines

Pop the cork! We’ve launched Part One of James Halliday’s Top 100 wines. Celebrate with a glass of affordable Tasmanian bubbles or a sparkling 2013 vintage Dom Perignon.

The best 20 premium red wines

Which wine has James Halliday called ‘the greatest Australian pinot noir I’ve ever tasted’? Discover this all-time great among his pick of Australia’s best reds of the year.

Cheers! These are the Top 20 beers of 2023

Whether you want a pale ale, a dark ale, a strong ale, a lager, a Pilsner, a sour, a stout or a non-alcoholic drink, then Peter Lalor has you covered. It is, as a beer drinker, the best time to be alive.

Top 20 white wines over $30

Discover a 99-point Margaret River blend with perfect balance, two delicious Hunter Valley 2017 semillons and an irresistible Clare Valley riesling. These are Halliday’s top picks of 2023.

Best Australian spirits of 2023

Absinthe from McLaren Vale? Hot Chip Potato Vodka? Nick Ryan’s list of craft spirits will knock your socks off.

The best alcohol-free cocktails and spirits

I used to write New York’s hottest column about bars - now I’m off alcohol altogether. Here’s what I drink instead.

Australia’s best white wines … and they’re all under $30

One varietal above all others is offering the best value wine in today’s market. Find out which, and discover 20 of the tastiest budget drops James Halliday has judged in 2023.

Best Australian red wines under $40

Australia’s premier wine critic James Halliday has selected the very best value Australian red wines on the market – and it includes a ‘beautifully-balanced bargain’.

Today, Walpole’s vineyard is a patchwork of varieties few people would recognise, the fruit of which goes into his Fighting Gully Road wine, which he makes in a former mental asylum in Beechworth.

He’s currently crazy about aglianico, a southern Italian black grape variety planted in the alpine valleys in 2009. He calls it a classic climate change selection. “It was marginally too cold when we did, but we knew as things warmed up it would grow into its space.”

Obscure varieties are enjoying a moment in the sun, finding a niche in a wine landscape rapidly recalibrating to the realities of changing climate, a challenging (read: dire) export market and the shifting whims of a younger generation of wine drinkers.

But how long does it take for a new variety to become an overnight success? And are Australian consumers ready for a new set of wines, with names they as yet can’t even pronounce?

South Australia’s Riverland is Australia’s largest grape growing region, the “cardboard box” heartland of wine making. It’s hot and dry, and almost a third of Australia’s total grape crush comes from here – typically shiraz, chardonnay and cabernet sauvignon sold in bulk to large wine companies. The reputation here has always been quantity over quality. But for the past 20 years viticulturalist and winemaker Ashley Ratcliff has been doing something out of the cardboard box, causing the region to re-evaluate this role.

Ratcliff tried to ignore the funny looks he got in 2003 when he bought his Ricca Terra vineyard and started replacing the in-demand cabernet sauvignon with trebbiano, fiano, vermentino, albariño and greco – varieties no one had heard of, or was much interested in.

“It was a risk,” says Ratcliff, “but it was more of a risk not to take that risk. Our view was if we did nothing we’d look like our neighbours in 20 years. So we planted varieties we thought would be best suited to a warming climate. The worst thing [that] could happen was we’d have a vineyard full of interesting grapes.”

He now grows more than 50 varieties, mostly Italian and all better suited, he says, to the changing climate than the conventional varieties he ripped out. He says lighter alternative varieties are well suited to the changing demographics of wine drinkers.

“A lot of people don’t want to drink what their parents were drinking, like a big Barossa shiraz,” he says. “We’ve got the opportunity here to make a name for growing nero d’avola, the same way Margaret River got its name for cab sav. I’d rather have a variety that’s in growth, even off a low base, than one that’s in decline.”

Bruce and Jenni Chalmers operated the vine nursery in Euston, NSW, that propagated the 70 Italian varieties Mark Walpole imported in the 1990s. Every vine of nero d’avola currently growing in Australia can be traced back to one pot plant. In 2003, right at the beginning of the millennium drought, the Chalmers family trialled making wines from alternative variety grapes grown at their new vineyard in Merbein, near Mildura in Victoria, one of the hottest wine regions in Australia. The extremes were tested even further in 2017 when vines of inzolia and negroamaro were planted and then progressively starved of water to test the limits of their drought tolerance. Known as the “bush vine project”, the vines receive no traditional irrigation, getting instead an occasional top-up from overhead sprinklers. “The average irrigation for our region is 600mm,” says Kim Chalmers, who is now the director of the business. “Last year we did the equivalent of 24mm. And the wine is fantastic.”

Chalmers says it’s not only about identifying climate-appropriate grapes, but turning around the stigma of inland wine regions, pushing back against the commodity image and proving that great wine can be made anywhere, provided you know what you’re doing. “There’s a stereotype that cool climate is premium and warm climate is not. That’s why I love our bush vine wines,” says Chalmers, “because they’re smashing stereotypes.”

But are alternative varieties smashing it in the marketplace? Going on raw figures you’d say not. Shiraz and chardonnay alone still constitute nearly half the total crush in Australia. Sangiovese broke into the top 10 on volume this year, with just over 5000 tonnes crushed. In comparison the figure for shiraz was 346,000 tonnes. Even prosecco, well entrenched in the top 10 of white varieties, still only registers 1 per cent of the white grape crush. In all respects, the footprint of alternative varieties is tiny.

Or is it? Chalmers says the export market, dominated by shiraz, chardonnay and cabernet, has always skewed the figures. And just because grapes are being crushed doesn’t mean the wine is being sold. Recent analysis by Rabobank revealed an oversupply of around two billion litres of commercial wine, with grapes being left to rot on the vine and prices crashing. In 2019, shiraz exports earned $780m. This year it’s $384m. A reset could be sorely needed.

“If you get away from the cold stats and look at wine lists and bottle shops and wine reviews you’ll see that interest [in alternative varieties] is surging,” says Chalmers. She has no doubt that wines currently considered obscure and unpronounceable will soon have their time and, like prosecco and chardonnay, will become part of our vocabulary.

Winemaker Jo Marsh of Billy Button Wines has a way of dealing with unpronounceable wines. Marsh is something of an alternative variety evangelist, making wines from 26 different types of grapes grown in Victoria’s Alpine Valleys region. She favours Friulian varieties: textural, savoury whites like malvasia, friulano and verduzzo, and elegant, peppery reds like refosco and schioppettino. Angst over pronunciation is a big hurdle for people to overcome, according to Marsh, and is the reason all her wines have nicknames. Schioppettino becomes “The Surreptitious”; gewürztraminer becomes “The Happy”; grüner veltliner becomes “The Groovy”. While some of Marsh’s varieties remain fiendishly obscure, others such as vermentino, fiano, sangiovese and tempranillo she now considers “mainstream alternative”.

She says the relative anonymity of the Alpine Valleys means it hasn’t been encumbered with a reputation for any traditional variety, so has clear air to write an alternative narrative. “It also works to our advantage on wine lists,” she says. “Instead of fighting for the two or three chardonnay or shiraz spots, we have many options to fill out the list.”

She has no doubt wine drinkers are becoming increasingly adventurous, and will usually choose to buy an alternative variety after doing a tasting at her cellar door in Bright. Retail is a bigger challenge. “People generally don’t pick a variety they’re never heard of off the shelf in a bottle store,” says Marsh.

Proving the point that change is afoot is McLaren Vale winemaker Corrina Wright (see Q&A, page 11). Wright says it was “pretty weird” when her grandfather Bert Oliver planted the region’s first chardonnay vine in the 1970s. But the grape quickly became synonymous with the region, along with shiraz and cabernet sauvignon. Now that’s changing, as the move to climate-adapted alternatives gathers momentum.

Wright’s been leading that charge, ripping out her grandfather’s chardonnay and grafting in varieties like fiano and sagrantino, and swapping out cabernet for the Spanish variety mencia. She says there’s been a dramatic reduction in the three major varieties throughout McLaren Vale, with the space being colonised by alternative varieties. She thinks it will only increase. “There’s huge untapped demand for alternative grapes,” she says. “Fiano never lasts a year without selling out. It’s got great natural acidity, a beautiful textural element, and it’s drought and heat tolerant. What more could you want?”

Wright is also president of the Australian Alternative Varieties Wine Show, now in its 22nd year. Based in Mildura, the annual awards attract 800 entries from around 115 different varietals. She says one of the most rewarding aspects of running the show is graduating grapes no longer considered alternative, such as prosecco and pinot grigio; wines that went from nothing to mainstream. “We’ve just graduated durif, and next year will probably be tempranillo, then fiano.”

For these future-focused winemakers, it’s about looking 20 years ahead, planting for the environment and the climate, and hopefully finding the next prosecco. It might just be falanghina, a late-ripening, aromatic riesling-esque white from Campania in Italy, currently only being made by Chalmers Wines. “It will become part of the Australian wine landscape in warmer regions, without a doubt,” says Chalmers. “Our decisions on what to plant are made based on how the varieties will perform in our soils and the climate. We don’t deal in trends. We deal in reality.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout