The march of progress

But the reign of the word processing operator was short-lived. By the late 1990s, another technology emerged that would obliterate them from the office landscape. That technology was the desktop computer, soon followed by a sleeker version known as the laptop, which has survived in ever thinner and faster formats. The revolutionary aspect of the laptop wasn’t so much its ability to produce a report or send an email from more or less anywhere at any time. It was its effect in upskilling the entire workforce in typing skills. No need for a typist; with the advent of the laptop everyone learnt how to do it. Initially it was with only two fingers but it was sufficient to reshape and reskill the office workforce.

Almost immediately the role of secretary changed; no need for someone to fetch files, type memos, track expenses or photocopy documents. All these menial tasks are now managed by some form of technology, freeing up secretaries to reinvent themselves. Indeed, secretarial skills are now far more likely to be deployed in a broader role such as office manager. Although, with more people working from home, maybe there’s a need for a new job title such as “workflow co-ordinator” to manage out-of-office teams.

Technology transformed jobs outside the office too. Petrol pump attendants, for example, didn’t survive the 1980s; today a petrol station with attached mini supermarket can be managed by a single customer-facing operator. This model of service delivery didn’t so much require new technology as it did the co-operation of customers to pump their own petrol. Customers, it seems, would rather manage a transaction than queue for service. The same goes for supermarket checkout operators, whose role is being eroded by advances in scanning technology and by customers preferring to be in control of the process. Self-service checkout facilities have steadily gained ground at the expense of the human experience.

The driving force behind all this change is the pursuit of efficiencies. And that is what new and especially digital technology does so well. But none of this change would be possible without customers and workers enabling the new technology. We have learnt how to fill petrol tanks, purchase cinema tickets online, to type, format and save reports, to check in our own bags at an airport. We shuffle funds from one account to another without the aid of a teller. Customers, workers and patrons are doin’ it for themselves. All they need is the new technology, a bit of training and they’re experts. The primal urge to be in control, to manage the process, does the rest.

What else will we customers be doing for ourselves in the future? Maybe the real revolution lies just around the corner as technology starts whittling away at the skilled labour requirements of the care and wellness industry, education services and even professional services. The point is that while new technology can be frustrating – even maddening – in its incessant demand for continual learning, it is being enabled by our outrageous expectations for our quality of life.

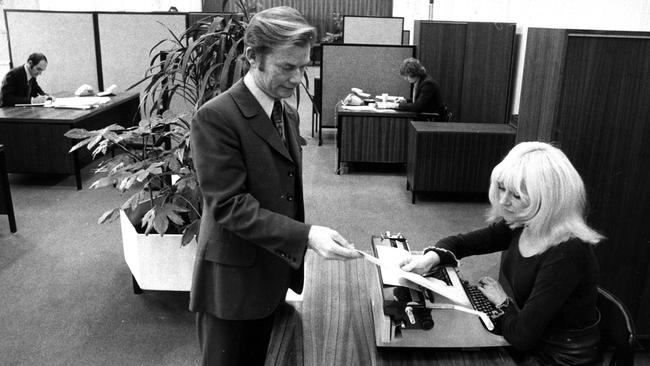

In the late 1980s there was a brief tussle for supremacy between two lifeforms that roamed the office landscape. The loser was the typist, who lived in a typing pool with other typists. The winner was a nimbler lifeform that went by the title “word processing operator”. Of course, typists could reinvent themselves as word processing operators if they trained in the new technology. I’m sure many did precisely that. But others didn’t; they either retired or sought out a workplace that was happy to traipse along with old tech.