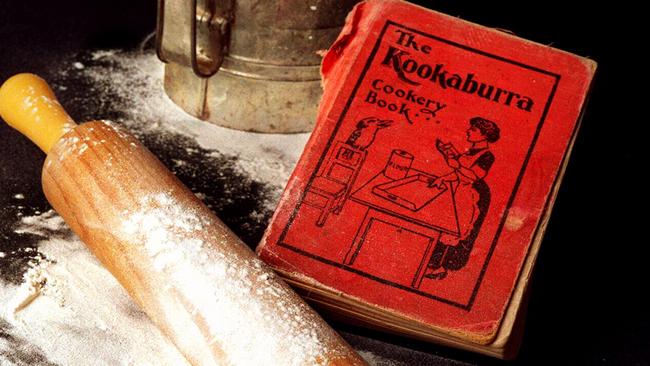

Also in the home is a less celebrated but even more valuable artefact that has the capacity to pass on stories, insights and messages through the decades. I speak of the humble recipe book. More than a mere collection of recipes, it captures the times. Assembled with familial love and purpose and kept in the hearth of the home, it is regularly referenced and built upon, much like a photo album, and encapsulates the essence of a person who has lived, loved and cooked.

When my mother died two years ago at the grand age of 95, I gathered up her kitchen belongings including a battered recipe book that I recognised from my youth. It begins in 1940 with her name and address. She was 14 at that time. Her cookery book, as she called it, comprised an Embassy exercise book with three recipes per page over 80 pages. Each recipe was carefully written in her distinctive cursive using a pen dipped in blue ink.

On weekends while I was in primary school she taught me how to bake, sift flour, knead dough and pour a mixture into “patty pans” for what we now call cupcakes. (She also taught me how to darn socks, use a treadle sewing machine and knit.) She would whistle the Irish tune Molly Malone (“cockles and mussels, alive, alive-oh!”) while whisking around the kitchen of our Commission house on baking day.

The recipes speak of wartime. There’s an austerity pudding that includes dripping and golden syrup; recipes for substitute cream and “butter substitute”; and another item, bluntly called “war loaf”, also made with golden syrup. Her cookery book contains recipes for melting moments, for orange sponge, for lamingtons, but every so often there is a digression. She wanders off and includes a list of her favourite songs, no doubt heard over the wireless: Kiss Me Goodnight Sergeant Major, Goodbye Sally and Little Brown Jug. Later there’s the Beer Barrel Polka and (Bing Crosby’s) Sing a Song of Sunbeams. There’s an irrepressible joy to this selection, to this distraction from the otherwise orderly recipes. Even amid the depths of war, in the remote farmlands of Western Victoria, a teenage girl sees warmth, happiness and hope for the future. This wasn’t just a cookery book: it was part of her trousseau for her future household and family.

Beyond the recipes there are helpful hints, including “to get rid of rats sprinkle their haunts with sulphur”. There’s also a list of remedies for afflictions including a poultice for chilblains comprising reduced vinegar and alum. I suppose living remotely at that time required not just self-sufficiency in cooking but also being able to manage vermin and illness. These challenges, along with war rationing, belong in a different era, together with cursive writing, inkwells and happy songs.

A humble artefact from a modest home can tell a far bigger Australian story. How many other such recipe books are out there that capture the essence of an earlier Australia? How should these artefacts be passed on to the next generation? Should they be digitised, or held in some kind of library? Or should they be passed on in the hope that they survive the shifting and shuffling of the next generation as they live their busy lives?

Some of the most valuable sources tracking social and cultural change are held, and passed on, within the family home. The old-style photograph album is the repository of images that capture the comings, goings, joys and sorrows of family life. Now, in the digital age, many of these photographs can live in perpetuity, reminding each generation of the stock and the circumstances from whence they came.