The stalwarts of everyday life that delivered safety and surety – the church, the workplace, the so-called natural order of things – were about to be challenged. The curtailed rights of women. The abuses of the church. The disenfranchisement of Indigenous Australians. The lack of recognition of same-sex relationships. Some of these issues would be tackled before the end of the decade; others, years later.

Compared with 60 years earlier – around the time of Federation – I am not sure that a great deal had changed. Sure, technology had evolved by the post-World War II era. But my parents (living in country Victoria) didn’t get a refrigerator until the late ’50s, a washing machine until the early ’60s, or a TV until 1964. We didn’t even “get the phone on” until 1974. Middle-class ideas such as eating out at a cafe, inviting people other than immediate relatives into the family home (for something like a dinner party), or going away for a holiday were, for most Australians, not part of everyday life prior to the 1960s.

From Federation, push back another 60 years to the pre-Gold-Rush 1840s – just 60 years after European settlement – and Australia was comprised of a series of colonies desperately clinging to the edge of the known world. There was no evolving middle class at this time, only administrators, squatters, labourers and a few shopkeepers thrown in for good measure. In some colonies there were also jailers and the jailed.

The era from the Gold Rush to Federation laid the foundation for an independent nation: we built railways; we pushed farms and towns deep into the interior; we built factories, schools, churches and council chambers. But again, many aspects of everyday life didn’t change much. What we ate, our belief systems, how we organised society wasn’t that much different for folk across the second half of the 19th century, especially in non-metropolitan Australia.

But looking across time this way, comparing how we lived, worked and even formed relationships at 60-year intervals, brings into focus common themes in Australian life. What is evident is our industry, our willingness to embrace new technology when it becomes available to us, and our collective determination to build a fairer and more equitable country.

What is less evident, I think, is a clear and immediate connection between the arrival of new technology (and the consequent raising of living standards) and our questioning, as a society, of prevailing ethical issues.

Social change began slowly in Australia, but it did gather momentum as prosperity increased. Our pursuit of social justice – as it is currently perceived – is further evidence that we are forever trying to build a better version of our community. The bigger question is how the Australians of the 2080s will view our efforts today: what priorities (indeed fervent obsessions) of ours might they confidently rejig in their pursuit of building a better Australia?

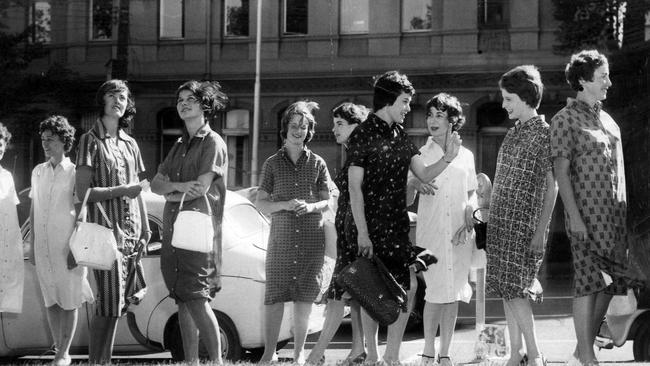

Come with me on a journey back in time, starting with the early 1960s when the baby boomers were kids. This was a time before the cultural revolution of the late ’60s, a time when the social and political influence of the UK was still evident. It was an era in which we drank tea, trucks were called lorries, takeaway meant fish and chips, God Save the Queen was our national anthem, and ladies might be asked to “bring a plate” to social gatherings. It was a time of great innocence for some, of great despair for others.