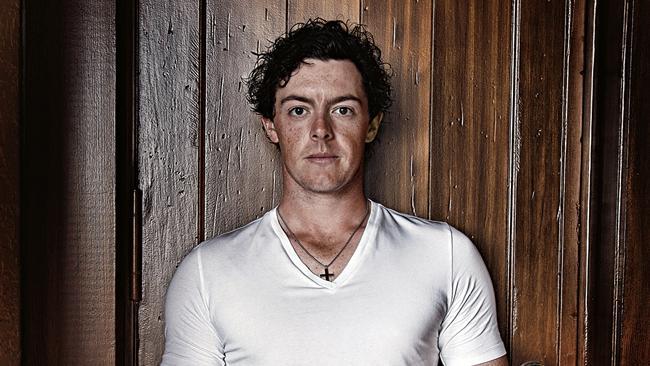

Rory McIlroy: Erica Stoll, the US Open and the secrets of his success

On the eve of the US Open, world No.1 Rory McIlroy reveals how he learnt to be a winner… and what makes him cry.

It would be stretching things a little to say that Rory McIlroy cries when I meet him the day after his victory at the Wells Fargo Championship in the US, but he certainly comes close.

We are in a modest function room at a hotel in London, the world’s No 1 golfer wearing a baseball cap and orange top and sitting upright on a small chair. Short and bright-eyed, it is odd to think that he’d been in America the evening before, completing a record-breaking victory – he ended the tournament 21 under par – and pocketing a cheque for $US1,278,000. He has flown in overnight, slept for four hours on the plane, and faces a full day of media engagements. But suddenly that boyish face starts to reveal tension, his eyes watering as he attempts to control emotions that have, rather unexpectedly, come to the surface.

The discussion is ranging far and wide. We talk about his spectacular implosion at the Masters in 2011, when he squandered a four-shot lead in the final round at Augusta at a crucial moment in his fledgling career; his redemption at the US Open a few weeks later, when he finally proved that he had the mental toughness to win a major; and the deal he signed in 2013 with Nike, rumoured to be worth $150 million, which for a time placed a weight on his shoulders that he “struggled to deal with”.

The 26-year-old is even content to discuss his personal life following the ending of his relationship with Danish tennis star Caroline Wozniacki in May last year, a split that created headlines on the back and front pages. “I have met someone new,” McIlroy says. “She doesn’t play golf, but she is involved with golf. I have known her for three years and we are good friends ... If everything off the golf course is good, it allows you to be better on it as well.”

But it is when I ask him about his parents, Rosie and Gerry, and the role they have played in his development as a golfer and a person, that McIlroy – to his surprise as much as mine – begins to well up. At first, he is composed as he describes growing up in a two-up, two-down terraced house in Holywood, a small town outside Belfast, Northern Ireland, the only child of a father who worked as a cleaner and barman and a mother who volunteered for extra night shifts at a factory to fund her son’s golf career. “My parents worked ferociously hard,” says McIlroy, who started playing regular golf at the age of two. His dad was a scratch golfer, but in contrast to Tiger Woods’ father, who was pushing him towards the big time almost before he could walk, Gerry McIlroy didn’t have ambitions to steer him into the professional game if that wasn’t what his son wanted.

“I always remember my dad working three different jobs, for more than 90 hours a week,” remembers McIlroy. “He only got Wednesday nights and Sunday afternoons off and I am sure he would have loved to sit in the house and relax, but I would drag him to the golf course or the driving range. All the way through my youth, he did what I wanted to do rather than what he wanted to do. My mum was the same, working round the clock to help pay for my tournaments when I got to nine or 10.

“At that age, you just don’t realise the scale of the sacrifice. I thought that it was normal; it’s what I had got used to. Looking back today, I realise that it was anything but normal. They were not at all pushy; they just wanted me to develop in the game that I loved. If anything, they tried to guide me into other sports to give me more variety, and always encouraged me to focus on my schoolwork.”

McIlroy pauses. He gulps. His eyes fill. It takes him a second or two to compose himself, and he smiles, almost apologetically, as he does so. Outside, you can hear TV cameras getting into position. There are hushed conversations between various media crews waiting to get a piece of the action. But in the quiet of this small room, with its minimalist furnishings, McIlroy is contemplative, considering what really matters. He talks slowly, almost earnestly, as if eager for you to know that he means what he says, sitting perfectly still and maintaining constant eye contact that, were it not for the warmth in his expression, might be unnerving.

All too often today, parents are scapegoats, convenient receptacles for the angst and neuroses of their offspring. So McIlroy’s gratitude to his mother and father comes across almost as revelatory. These days they live half their time in Ireland and half their time in America, he says, so he still sees a lot of them. “But I will never be able to do for them what they did for me. I will never be able to repay them for that… But I hope they know how much it means to me. There is nothing more important.”

McIlroy is one of the most bankable sports stars on the planet. Golf moved into the mainstream with Tiger Woods, and has become a huge industry with commensurate prize money. It has its own TV channels, magazines and vocabulary. Merchandising and equipment are multi-billion-dollar businesses. Golf generates $70 billion in annual revenues in America alone, according to a Bloomberg report; the equivalent figure for Europe is 15 billion ($21 billion), says the PGA. Aspiring players these days are drawn not just from golf’s traditional heartlands such as America and Britain, but also from Asia and South America.

The competition is fierce – but there is no doubt who is the top dog right now. McIlroy is not merely the world No 1; he is one of the finest talents the game has seen. Already, he is being measured not just against his competitors but also against the giants of the past such as Jack Nicklaus and Ben Hogan. (Nicklaus is among many golfing greats in awe of McIlroy, stating last year that “Rory has an opportunity to win 15 or 20 majors or whatever he wants to do”.) McIlroy has won three of golf’s major titles: the British Open in 2014, the US Open in 2011, and the PGA Championship – twice – in 2012 and 2014. Last year, according to Forbes magazine, he earned $US24.3 million. He’s recently missed two cuts, including the Irish Open, but is favourite to win the US Open, starting Monday. Tiger Woods is still a bigger draw for multinational sponsors, and out-earns the Northern Irishman off the course, but Woods’ 2009 confession to a string of infidelities and subsequent dip in form took the wind out of golf’s sails somewhat. McIlroy has become the great hope of the sport, the man who can take it to new markets.

I followed McIlroy during the British Open last year, which he won in impressive fashion, and his ball-striking had an entirely different quality to his rivals’. That compact frame (he’s 1.73m tall and weighs 73kg) and the torque he produces through the rotation of his body contributed to a distinctive ping. It wasn’t just about power, however, but timing. There was cleanness in the contact, a sense of intimacy between the artist and his art. As one commentator put it: “He strikes the ball in a purer way than anybody else in the world of golf.”

I ask McIlroy how he has sustained his motivation through all those years growing up, and the thousands of hours he has clocked up as a pro. The rewards are huge, but has he ever wished for another kind of life? He smiles. “I remember when I was 17, I had just won quite a big amateur competition in Ireland and Dad was driving me home. But for some reason, I didn’t feel anything. I had won, but it didn’t register. I said to my dad, ‘I don’t want to play any more.’ He was like, ‘That’s fine, OK. Go and do whatever you want, your mum and I will support you.’ I didn’t play for three or four days, and then I was itching to get back out there. I just needed a break… It showed me that, even when you love doing something, you need to take a step back every now and again.”

The most significant turning point in his career came on April 10, 2011. This is when he was on the cusp of his first major, leading the Masters in Augusta on the back nine of the final round. But he hit a wayward tee shot on the 10th and proceeded to implode. He scored a triple bogey, and followed it with a bogey and then a double bogey at the 11th and 12th. It was a humiliation so public that many commentators wondered if he would ever recover. On Twitter, Ian Poulter, his Ryder Cup team-mate, posted a health and safety sign: “First Aid for Choking”.

But McIlroy was resolute. “It was all about turning disappointment into motivation,” he says. “I thought to myself, ‘What I showed out there, that is not me. That is not who I want to be. I want to be a gritty competitor. I want to be able to close the deal. I don’t want to crumble under pressure.’ And I said to myself, ‘I am never going to let that happen again.’ I went home and analysed it. I watched the round on video. I talked to a few people… And I realised that I was way too focused. I was thinking about the round overnight, during the morning; nothing else was on my mind. I was thinking about what could go right, but also about what could go wrong. I was too anxious and wound up. That is no state of mind in which to perform.”

Two months later, he had a chance to deploy a different mental strategy when he led the US Open by eight shots going into the final day. Instead of agonising overnight about his final round, he switched off. “What I learnt from Augusta, and what I try to put into place every round now, is getting my mind away from the intensity and pressure. Even between shots, I have learnt to switch off. I talk to my caddie about a movie that I saw the night before, or a football match. Sometimes, I will tell JP [his caddie] to talk to me about a film, a match, anything to stop me focusing too hard.

“Only as I approach the ball do I switch back on. This means there isn’t enough time to think about what might go wrong, for negative thoughts, for doubts to creep into your mind. All you have time to do is to consider the shot in hand, pull the club from the bag, and visualise what you are going to do next. I am a very visual person: I create a picture of the flight of the ball, seeing in my mind what the ball is going to do. And then the final piece is to strike it.”

In early 2013, McIlroy faced the only other serious wobble of his career. He signed a deal with Nike, reportedly worth $150 million over five years. There was a glitzy unveiling at the Fairmont Bab Al Bahr hotel in Abu Dhabi. His form almost immediately slumped. “I’d never had expectations placed on me by a sponsor like that before,” he says. “It was the first huge deal that I had signed. There was a lot of hype and it was something I had never really experienced before. I had won big tournaments, but I had played with the same clubs that I had always played with since 15. Then there was this big reveal in Abu Dhabi and I honestly felt an incredible pressure. And, you know, I went through a period where I wasn’t swinging my best. Maybe I was trying too hard to prove that this isn’t going to make a difference to my game. I just needed to go back to the drawing board, look backwards to go forward. Mentally, I was putting a lot of pressure on myself, and that’s when things can start to go wrong.”

It was another lesson in the importance of the mind in this most psychological of sports.

As he talks, I realise what a remarkable young man he is. I had half expected to be disappointed by McIlroy. Many top sportsmen tend towards narcissism. Perhaps it’s an inevitable consequence of being indulged by a large entourage. They openly display their boredom during interviews and can be difficult to warm to. In the case of McIlroy, all I see is a young man who adores his parents, who is courteous to those around him, and who approaches his sport with the professionalism and resilience that is the hallmark of great athletes. You have to admire his ambition, too. He started playing very young; by the age of two he was hitting balls 35m with the plastic club his father had bought him. At nine, he appeared on TV chipping balls into his mother’s washing machine and was winning competitions in the US. Today, he remains driven by a powerful desire to become the game’s greatest player. His work ethic has never wavered. “I feel as if this is the time to put my mark on the game,” he says.

Today, McIlroy lives in Palm Beach, Florida, and his private life seems in order after a torrid year. He’d proposed to Wozniacki during a New Year’s Eve boat trip on Sydney Harbour, presenting her with a $200,000 diamond ring. But five months later, in May last year – days after the wedding invitations were sent out – he called it off in a phone call to the tennis star. He later declared in a statement: “The problem is mine. The wedding invitations issued at the weekend made me realise that I wasn’t ready for all that marriage entails.” Now he has a new love, Erica Stoll, a 29-year-old who works for the PGA. “I am very happy in my love life,” he says. “We haven’t really been putting it out there. She is from America, which is why I like to spend time in Palm Beach… The past six or seven months have been really nice. That part of my life is going great.”

There are clear skies in another part of his life, too: a long, bitter contract dispute with his former management firm, Horizon Sports, came to an end in February this year after McIlroy paid a reported $30 million to settle the case and avoid having to take the stand at the Irish High Court in Dublin, at a trial scheduled to last eight weeks. McIlroy had previously called the legal battle “a very tedious and nasty process” – but now that’s behind him.

That $30 million will only put a temporary dent in his bank balance. And for all his huge wealth, McIlroy describes himself as a “home bird” first and foremost. “I will always go back to Ireland, and I love seeing old friends. I don’t like to go to red-carpet events, or socialise with celebrities. It’s just not me. I’d much rather be at home with friends and family, people who actually know me… I have five or six friends from Holywood who have known me since I was a kid. Some were with me at the tournament last week. They’re really important to me.”

As our interview comes to a close, we turn back to his parents. McIlroy famously broke down after the 2011 Masters during a phone call to his mother. “It all sort of hit me,” he recalls. “Whenever you hear or see someone cry who you love, it sparks that emotion in you as well.” The only other time he has come close to tearing up because of golf was in very different circumstances. At the British Open in 2014 he dedicated the win to his mum, who embraced him on the final green. It was the first time she had attended the final round of a major. “She was crying her eyes out, and I almost started, too,” he says. “It was a special moment.”