Red imported fire ants, electric ants, yellow crazy ants: will they take over Australia?

New and lethal ants are threatening to ruin our lifestyle. Stopping them has already cost hundreds of millions of dollars.

When a single red imported fire ant nest was discovered at Port Botany in Sydney in November — the invasive species having evidently arrived on a cargo ship from Argentina — news reports declared it “threatened to ruin the Australian way of life” and might “cost the economy billions”.

The NSW government’s response to the first reported outbreak in the state comprised a 25-strong swarm of biosecurity and pest experts, aided by three “elite” odour detection dogs with enough snout-power to zero in on a single ant. Poisons were laid and hundreds of home gardens searched up to two kilometres away in an operation leaving little to chance. No more nests were found, but a 500ha surveillance area has been declared by the NSW Department of Primary Industries.

The dogs were on loan from Queensland, where, since 2001, close to $300 million has been spent through the National Red Imported Fire Ant Eradication Program trying to oust the pests from around Brisbane, so far without success. Any failure to sustain that effort could mean Australia will end up like the southern US, where, to quote Texan entomology professor Bradleigh Vinson in American Entomologist, people in fire ant-infested areas “do not have picnics on the lawn, go barefoot, sit or lie on the ground or stand in one place without constantly looking at the ground near their feet to be sure the ants are not swarming up their legs.”

Australia abounds in assertive insects but none of them operates like these fire ants, part of a group known as “tramp” ants because they travel so freely. In the US they cause such unlikely problems as fires, potholes, computer failures, crop losses and blindings of farm animals. More than 80 people have died from the stings, mainly of anaphylactic shock. A growing problem in nursing homes is elderly patients killed by ants in their beds. One woman died in a house fire after fire ants caused a short circuit. When one ant is electrocuted the pheromones it releases attract its comrades, until the masses of dead bodies trigger failures of light switches, air conditioners, traffic lights, pumps, meters, even car electrical systems. Americans spend more than $6 billion a year dealing with the many problems.

The question for those who live in areas infested by fire ants is not whether they will be stung but how often. An early 1990s survey of medical students in Texas found more than half had suffered in the previous three weeks. One sting isn’t too bad — like a light brush with nettles — but each fire ant can strike multiple times, and each sting causes a weal and flare followed by a pustule. Scores or even hundreds of ants may climb a victim’s legs before they sting in unison. Clothes are sometimes torn off in the panic.

Other nasty ants have appeared in Australia in recent years, including one that attacks people in their swimming pools. Electric ants — named for the shock of their stings — are tiny, just 1.5mm long, and when they fall from trees they float on water in substantial numbers. Gary Morton, who runs the National Electric Ant Eradication Program, initiated after the ants were found in Cairns in 2006, told me they deliver “instantaneous pain then throbbing that lasts for a few hours”. One person was stung in the bath, another on the toilet. “We found foraging lines going up the bowl,” says Morton. In the Solomon Islands, where these ants are entrenched, some residents keep their bed-legs in cans of water to thwart nocturnal stings. In New Caledonia, scores of dogs and cats are blinded after ants commandeer their food bowls.

The federal government has provided $2 million to battle yet another little critter — the yellow crazy ant — south of Cairns, lest north Queensland end up like Christmas Island, where they have killed more than 10 million red land crabs and hastened the extinction of a bat and lizard species. Andrew Maclean, executive director of the Wet Tropics Management Authority, says that if the yellow crazy ants — first detected in Cairns in 2001 — become entrenched in the neighbouring Wet Tropics rainforests, they will spray acid into the eyes of endangered cassowary chicks. When ant expert Lori Lach put hundreds of butterfly caterpillars into a crazy ant site in April last year, most were carried off inside three hours. One yellow crazy ant colony on a creek bank on the Atherton Tableland poses a conundrum: insecticides can’t be applied near creeks and the site is one of only 10 to host the endangered Kuranda tree frog. Conrad Hoskin, the James Cook University biologist who discovered and named this species, says he would rather see a whole frog population poisoned than have the ants spread.

In 2006, the federal government published a Threat Abatement Plan in an effort to reduce the impact of tramp ants on biodiversity. Of greatest concern are the fire ants found around Brisbane, the electric ants in the Cairns area and the yellow crazy ants spreading at several sites in Queensland and the Northern Territory. The first two could possibly thrive as far south as Melbourne; their footholds have more to do with their initial points of entry into the country than with their ideal climate range.

No one should suppose that modern technology has put us beyond the reach of harmful nature: in recent decades, horrific diseases have jumped from animals to humans — ebola virus, SARS, Hendra virus, bat lyssavirus. Tramp ants are a parallel threat.

For decades after fire ants reached the US in the 1930s from South America it was thought that each colony had a single queen. But in the 1970s they were found to be living in many places in the US in vast supercolonies containing many queens in networks of connected nests. Like slowly spreading liquid, supercolonies expand as young queens and workers crawl to new crevices. Instead of ants in adjoining nests fighting, they cooperate, and the energy saved flows to the common good: more ants. Fire ant supercolonies can achieve densities of 35 million ants per hectare; crazy ants can number more than 2000 ants per square metre over vast areas.

Melbourne is straddled by a colony of another invasive species of tramp ant, the Argentine ant — 80km wide, it is a city of ants overlaid on a city of people. Europe’s largest supercolony of Argentine ants runs 6000km around the coast from Italy to northern Spain. The world’s largest social units after ours, these supercolonies are the insect equivalent to the human nation states they now depend on.

Unbelievable ant densities help explain such improbable side-effects as pavements subsiding after fire ants nest beneath them, hatching sea turtles being overwhelmed and eaten, the deaths of chickens and calves, falling property values, parks that aren’t safe to walk through and crops that are hazardous to harvest. A surfeit of queens equips these ants for travel. Accompanied by a few attendants, a queen can enter mud stuck to a shipping container and see the world.

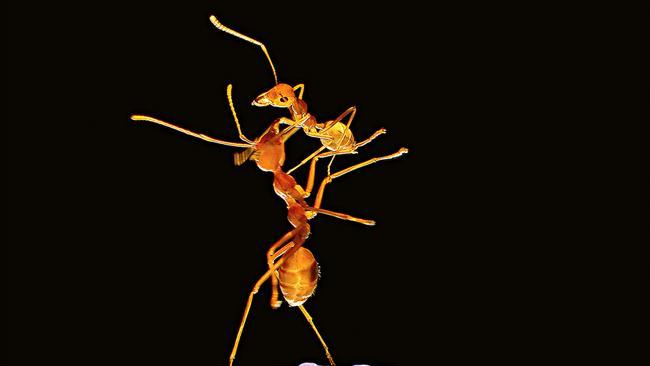

Ants are formidable adversaries because their social systems are in one way better than ours: when they pursue a goal, they don’t waver. Whether hauling crumbs across a blanket or fighting an enemy, they are unrelenting. Our quarantine and eradication efforts have not matched them for consistency.

Last year, at a Senate inquiry into biosecurity, the union representing quarantine officers complained of staff cuts leaving a “great gaping hole” in Australia’s northern defences; of detector dogs being removed from several ports; of soil on shipping containers that escapes inspection if bound for metropolitan areas, on the assumption that pest outbreaks in cities can be contained. In a survey last year, more than 70 per cent of staff rated biosecurity arrangements as “inadequate or really inadequate”. Global trade and travel keep increasing while quarantine budgets fall behind.

There is debate over whether federal and state funding will be sufficient to tackle what is a national threat — fire ants could invade 90 per cent of urban Australia. Recently, Western Australia stopped contributing after questioning the prospects of success. Yet as recently as March there was a renewed reminder that the ants are losing no time in advancing on new fronts.

Fire ant nests radiate heat, and the key to detecting them around Brisbane — where they are scattered sparsely across 340,000ha — is remote sensing with thermal imaging cameras mounted beneath helicopters. Sarah Corcoran, director of the Biosecurity Queensland Control Centre, which administers the fire ant eradication program, confirms that new nests have been found in the agricultural stronghold of the Lockyer Valley region, where a problem was first detected three years ago, and that a nest has been found in central Brisbane’s New Farm Park.

Governments today stress the importance of “intergenerational equity” as they strive to cut spending so future generations aren’t shackled with an unfair burden of debt. Biologists have identified another kind of liability: “invasion debt” — the future cost of battling pests that escape today. Australia is still paying dearly for the rabbits and foxes freed more than 150 years ago. The Queensland government has calculated that fire ants alone will cost the southeast corner of the state $1.4 billion a year if the battle is lost. Intergenerational equity justifies increased spending to avert the national version of that cost. But to win against invasive ants we also need to match their resolve. The benefits could be substantial, because there are other nasty ants on the move.

Biologist and author Tim Low served on the Biosecurity Queensland Ministerial Advisory Committee