Percy and Isabel Smith gave indigenous Alice Springs children the gift of opportunity – why were they forgotten?

Percy and Isabel Smith defied the racism of the day to devote their lives to giving Indigenous kids an education. Almost 80 years later the Smith family is fighting to preserve the couple’s legacy.

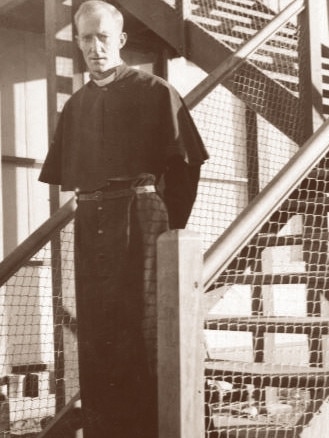

When Isabel Almond first met her future husband he was wearing a flowing priest’s robe and playing table tennis in a wooden hut in the middle of Australia.

Isabel was dating a soldier at the time, and he’d been posted to Alice Springs ahead of his deployment to serve in World War II. In the summer of 1940-1941 she decided to leave her home in Adelaide to visit him.

Isabel had grown up in the affluent suburb of Walkerville, where she went to the Anglican church every Sunday. She was a diligent student and a talented pianist, graduating in 1930 as an associate of the Victorian College of Music. Her parents expected that once the war was over she would marry her soldier beau and settle into a quiet life in Adelaide, working as a piano teacher and starting a family of her own.

Then Isabel met the Reverend Percy Smith.

Percy had been posted from Queensland to Alice Springs in 1933 to found the fledging Anglican parish in what was then a tiny service town in Central Australia. When Isabel arrived in town for a six-week stay to visit her soldier, the first thing she did was seek out the local Anglican church so she could worship every Sunday. It was here that she met Percy, decked out in his clerical finery and playing a vigorous game of table tennis with the children of his parishioners.

“He played in the cassock, which was quite unusual but typical of him,” Isabel recalled in a recently discovered interview from 1996 with historian Annette Roberts.

“I was expecting him to trip up but he had some means of tucking it up somehow around his belt. He moved around pretty fast, even with a cassock on, and he enjoyed every minute of it, being with the young folk. I just watched and enjoyed it. I’ll never forget it.”

The tale of Isabel Almond and Percy Smith is a love story in three parts: their love for each other, their love for outback Australia, and their love for its Indigenous people. It’s a story that challenges perceptions about the relationship between the Church and Indigenous Australians, which has often been held up as nothing other than damaging and paternalistic.

It is also a story that up-ends some of the mythologies surrounding the Stolen Generations, with Isabel and her future husband creating a unique and loving home and boarding school for Aboriginal children which became the engine room of unprecedented Indigenous achievement.

Among the boys in the couple’s care were those who went on to become Australia’s first Indigenous university student, its highest ranking police officer, the first to head a government department, the first to gain a PhD, three international soccer players, seven first-grade Australian Rules footballers and two rugby internationals. Seven became recipients of the Order of Australia, as did Percy and Isabel Smith.

Yet in the modern era the spectre of the Stolen Generations came to overshadow the Smiths’ work, framed around the flawed assumption that every Indigenous child in their care must have been wrested away from their parents. It tormented Isabel towards the end of her life, forcing her to give powerful evidence in defence of her late husband’s memory to the 1997 Bringing Them Home Report, denying that she, her husband or any of the institutions they ran were complicit in any way with the separation of Indigenous children.

While some of the children in their care had arrived after being stolen away from their parents, others had been abandoned by their parents, become lost, or had no known backstory. And many were entrusted to the Smiths’ care by loving Indigenous parents, knowing they would give their children the best possible chance in life, in much the same way white children are sent away to boarding school.

This boarding school model was what the Smiths wanted to create so that Indigenous children could learn alongside white children and gain an education. Their life’s purpose was to teach every child, black or white, and afford them with equal opportunities. This determination brought them into conflict with the widespread and racist view held then by many white Australians that Indigenous children simply weren’t worth educating.

Isabel’s story has come to life through the work of her grandson, Mark Smith, and through the interest of Hollywood director Mark Webber, who wants to bring it to the big screen in a feature film with the working title Finding Miss Almond. The project has been driven in part by the unexpected passing in November 2022 of Mark Smith’s father John – the only son of Isabel and Percy.

As he grieved his father’s sudden death from a heart attack, Mark Smith ploughed through boxes of documents and newspaper clippings chronicling his grandparents’ work, and decided to turn it first into a book and now a screenplay. “After my father’s funeral I was packing up his house and found one of my grandmother’s prayer books,” he says. “In the back were a series of handwritten love letters between her and Percy, folded neatly inside the back cover. Then I started looking at the diaries and the photos.

“Then by chance in January 2023 I was sent a 40-page transcript of an interview my grandmother did in 1996 with the author and historian Annette Roberts. The transcript brought my grandmother’s voice back to life for me, and includes crisp descriptions and rich detail which painted images [that I knew would be] perfect for scenes in a film. Without this interview the film script would probably never have been written.”

The three love letters Mark discovered tucked away in his grandmother’s prayer book were in no way steamy or salacious. Rather, they capture the excitement of Percy and Isabel about their pending life as a married couple and the work they planned to do together in Alice Springs.

In one letter Percy thanks Isabel for giving him new passion for their work, saying her love and support was driving him on. “It helped to bring out something good in me, something I thought I’d lost, something which gives me heart to labour long, long days,” he wrote in the months preceding their wedding.

But it was the 1996 interview with Annette Roberts that gave real impetus to Mark’s film project. The interview begins with the comic account of Percy’s table tennis exploits, but goes on to shed light on the qualities that made him so irresistible to his future wife. “He was unselfish and unassuming and humble,” Isabel says in the transcript. “Oh, humble in capital letters! People loved my husband for himself because that was him. Quaint. Unassuming. Gentle. Sincere. Loyal and reliable. A man of his word, and he’d do it through thick and thin.”

Isabel was especially taken by Percy’s determination to give Indigenous children a chance to succeed through education, and committed to working with him towards that end. It was a controversial view in that less enlightened era, when Indigenous children were ranked in the dreadful language of the time as “full bloods”, “half castes” and “quadroons”, and when white parents commonly insisted they did not want their children being educated alongside Indigenous boys or girls.

Percy was originally posted to Alice Springs because of a respiratory condition that saw him struggling in the tropical air of his native Queensland. Isabel says in the 1996 interview that she believed his posting to Alice on medical orders was an example of “the Holy Spirit at work”, given what he achieved for the children of Central Australia. As the first resident Anglican priest in Alice Springs in 1933, he was confronted on his arrival by dismal scenes at an institution known as The Bungalow, based at the Old Telegraph Station. It was in theory a “school” for Indigenous children but operated more as a holding pen, created out of what had been known as “The Half Caste Institution”, with a student body of around 100 at the time Percy arrived.

In her evidence to the 1997 Bringing Them Home Report Isabel recounted its shocking conditions. “There was an air of gloom and repression about the place and the children were silent and sullen,” she writes. “There was no laughter in the place. The superintendent did not do his job properly. The children were supposed to go to school but there was no teacher. One of the girls smuggled a letter out complaining of the treatment. The girls of all ages from babies to adolescents all slept in one dormitory that was poorly ventilated. There were rows of three-tiered beds. The boys slept in a separate dormitory.

“A new superintendent was appointed – a police constable and his wife. Things improved. Soon two teachers from the SA Education Department arrived and regular daily lessons were conducted, but the children took a long time to recover from the repressive treatment.

“Generally the white people had little regard for the mixed bloods. The children however had an engaging charm and responded to kindness, and even though it was still an institution ‘The Bungalow’ had become a happier place even though the children had very little.

“The general view was that these children weren’t worth educating and that they should be sent into the bush to fend for themselves. This viewpoint was unacceptable to Father Smith, who came to the conclusion that given the opportunity and away from the environment of being unwanted these children could hold their own.”

The first of Percy’s success stories was a young man by the name of Joe Croft, whose mother Bessie was of Gurindji/Malngin/Mudburra and Chinese heritage. What was then known as the Department of Native Affairs arranged for Joe to be cared for at The Bungalow. Percy quickly identified his academic potential, as demonstrated when he achieved high marks in the 1939 Qualifying certificate exam. He arranged to enrol Joe at All Souls School in Charters Towers, Queensland, where his brother, Cecil Smith, was on the school’s board of governors. Joe became school captain and after graduating won a government scholarship to study engineering at the University of Queensland. He is believed to be the first Indigenous Australian to attend university. When the war intervened Joe abandoned his engineering degree and enlisted to serve, later working as a surveyor and then as a senior policy advisor with the Federal Department of Aboriginal Affairs. To this day the University of Queensland bestows an annual Indigenous achievement award in Joe Croft’s name.

Yet in 1930s and 1940s Australia, Percy faced scepticism and even anger about his work. The furious resistance of some white families to the very concept of educating Indigenous children was documented by Isabel in the 1996 interview.

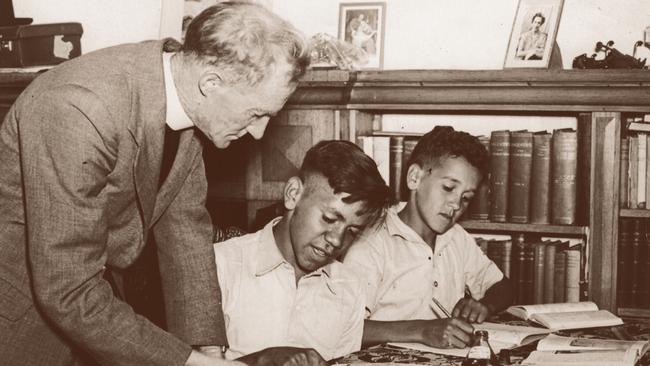

In 1941 Percy established the St John’s Hostel boarding house in Alice Springs, where children from white families living remotely could stay and gain an education. But Percy also transferred several Indigenous children from The Bungalow to St John’s, determined that they should have the same opportunities as the children of white farmers. “They were all the same to him,” Isabel said. “Treated the same. In the course of time he made that clear to the parents enrolling their children.”

One white parent who took umbrage was the wife of a local grazier, who had been aghast to learn upon visiting her son that he was sharing a dormitory with what she called “a mixed blood boy”.

Isabel recounted the conversation this angry mother had with Percy. “She said, ‘Father Smith, I won’t have my son sleeping in a bed next to a half caste boy! Half caste boys don’t come into our home.’

“So when Father had his say he said, ‘This is not your home. This is St John’s Hostel. I told you that I take a percentage of mixed blood boys but a greater percentage of white children because that’s how the hostel originated.’

“‘Oh but I don’t like it,’ she said. ‘Can’t you put him next to someone else?’

“That was her attitude. It was nasty.

“My husband said, ‘No, I haven’t any intention. It’s for you to make the decision. You go and think about it and you can take it or leave it. Let me know tomorrow whether you want him to stay or want him to go.’

“And that was that. She came back the next day much more humble and she said: ‘Yes, that will be all right.’ She knew she’d been doing the wrong thing. So that was his first victory. He was just trying to make them equal, as much as he could.”

Isabel and Percy were married on June 8, 1943. The time of the wedding was testament to their commitment to the children in their care. The ceremony was held at 7.30am, scheduled so the students from St John’s Hostel could attend a special wedding breakfast before attending school that day. For many of the Indigenous guests it was the first time they had been invited to a social occasion hosted by white people.

The couple stayed in Alice Springs for another 18 months, with The Bungalow finally feeling like a place of learning rather than a borstal for the boys.

Mark Smith never knew his grandfather, who died before he was born, but has many wonderful memories of talking to his grandmother about her work at St John’s Hostel. “My grandmother was kind, gentle, humble and devout,” he says. “She was softly spoken but determined on matters of principle. She loved children and wanted to be a teacher. Most of all she wanted to be a mother. This feeling was never stronger than when she met the Aboriginal children and their mothers in Alice Springs in the early 1940s.

“She was appalled by their living conditions, windowless tin sheds, heartbroken by the sadness in the children’s eyes, the pain and suffering. She could not stand by and do nothing. She left her comfortable life behind in Adelaide to go to Alice Springs and marry the priest. It was bold, especially given the threat of war from the north, and her parents naturally resisted.

“Even before the wedding her new life began. There was no time for settling in. She was straight to work at St John’s Hostel, cooking, serving, teaching, reading, cleaning and washing clothes. It was hard physical work but she loved it.”

When Darwin was bombed by the Japanesein 1942 the Federal Government ordered the transfer of Anglican children from The Bungalow to Mulgoa, on the outskirts of Sydney, for their safety. In 1945 The Bungalow was shut down completely, meaning its remaining students had to find somewhere to live.

At this point Isabel and Percy moved to her home town of Adelaide, determined to continue their work. Over a long period of time he had developed a strong relationship with many Indigenous people in Alice Springs who’d come to love and trust him. So when he proposed that he and Isabel bring six Indigenous boys to Adelaide in 1945 to further their education in a more conducive environment, the mothers readily agreed. The six boys were John Palmer, Malcolm Cooper, Charles Perkins, Peter Tillmouth, David Woodford and Bill Espie.

Using his own money, Percy arranged to house the boys in Kensington Gardens while they attended nearby Marryatville High School. Having exhausted almost all his savings, he secured donations from the Australian Board of Missions with which he was able to buy Glanville Hall in the seaside suburb of Semaphore. It was here that he established St Francis House, dedicated to the saint who was “the little friend of the poor”, where he could increase his intake of Indigenous students.

The roll-call of those who were cared for at St Francis House is an Indigenous Who’s Who of academic, professional and sporting achievement. Charlie Perkins was Australia’s first Indigenous university graduate and shot to prominence at the 1965 Freedom Ride and 1967 referendum before becoming the first Indigenous person to head a government department during the Hawke Government. Perkins was also a talented soccer player, trialling with Everton and Manchester United, but his soccer achievements were eclipsed by fellow St Francis House boy John Moriarty, who became the first Indigenous man to be selected for the national soccer team. Moriarty is better known today as the artist founder of the Balarinji Design Studio, which famously painted Qantas jets with Indigenous dot paintings.

Another of the soccer-loving St Francis boys, Harold Thomas, designed the Aboriginal flag. Gordon Briscoe was the first Indigenous person to gain a PhD in Aboriginal social and health policy, based on his work as the field officer for eye surgeon Fred Hollows. Les Nayda became a senior advisor to David Tonkin’s SA Liberal Government. Five St Francis boys played Aussie Rules at the highest level including Port Adelaide multiple premiership player Richie Bray. Vincent Copley played for Fitzroy, and Central Districts’ 213-game club legend Sonny Morey was last year’s honoree for the AFL’s Sir Doug Nicholls Indigenous round.

The story of how Sonny Morey came to be at St Francis House is a terrible example of the truth about the Stolen Generations, where some children were most definitely taken from their parents in the most callous and unjustifiable fashion. Morey came from a loving family and enjoyed a very happy traditional childhood in the homelands in the Eastern Arrernte in Central Australia. When he was eight years old he was playing with his cousin, climbing trees in the Todd River, when he fell and broke his arm. This accident brought him into contact with the authorities for the first time in his life, where it was decreed the accident must have been the result of parental neglect or poor supervision. He was put into state care and never saw his parents again. He was taken to St Mary’s Hostel in Alice Springs where he was put into classes despite being unable to speak English. At the age of 13 he was transferred to St Francis House where he befriended Moriarty and Perkins through a love of soccer, before discovering the game of Aussie Rules.

In the mid 1990s stories such as Sonny Morey’s came to be regarded as the only official version of how Indigenous children ended up in the care of the state and/or Church. There is also evidence that some people finessed their own life’s tales for the cachet of claiming Stolen Generations status. The sum result was that in the popular imagination, fuelled by party politics and cultural representations of the Stolen Generations in film and television, an uninformed and sweeping consensus grew that every Indigenous child being cared for by the clergy must have been dragged kicking and screaming from their parents.

This generalised slur tormented Isabel Smith in the years leading up to her death in 2002. It is what prompted her and her son to write their submission to the 1997 Bringing Them Home Report.

“We are deeply concerned that the work of Father Smith is being misrepresented by the emotive issues being presently investigated,” they wrote. “The work of Father Smith is being wrongfully associated with those people of Aboriginal descent who were in fact taken from their families by governments and others.

“Father Smith never did this and was in fact one of the first people in this country to stand up for these people when substantially the rest of Australia neither cared nor did anything.

“We strongly defend his honour.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout