‘I went through a stage where I just felt such an emptiness’: how Jacinta Price fought back from drug abuse hell

Drugs, booze, rehab: Senator Jacinta Nampijinpa Price’s life-altering journey back from the abyss.

Jacinta Nampijinpa Price is trying to shed her armour. If only for a day. She is reclining in a rocking chair on a veranda overlooking lush rolling hills near Tamworth in central NSW while her energetic Scottish-born musician husband Colin Lillie darts about ahead of his gig at the Tamworth Country Music Festival. This is Price’s happy place, where she and Colin can revel in their shared love of music and leave behind the bloodsport of federal politics.

“Here I am just Colin’s roadie,” she says of their annual visit to the festival. Nearby is the caravan they’re staying in, perched on the hill and notable for the Australian flag flying from a pole above it. It’s a few days before Australia Day and Price’s efforts to escape the world – or “take off her armour”, as her husband puts it – are failing. Her phone is buzzing with media requests to talk about her well-known pride in Australia Day. It’s the topic which, back in 2016, first catapulted Price to national attention when she wrote an impassioned defence of the national day in a social media post.

“I love this country for what it has given me,” she wrote back then. “I feel people choose to be a slave to an ideology that paints whites as oppressors and racists, and blacks as victims to be mollycoddled. I feel that Australia Day, nowadays, at the heart of it, is being used as a political platform for this ideology.”

“WHAT?”, others screamed in horror. An Indigenous woman embracing Australia Day? The day of invasion, of white colonisation? How could she say such a thing? Where is her black armband? Why is she so proud of this country? Who is this Jacinta Price?

Almost a decade on, Price is no less provocative. Now a household name after her high-profile role for the No campaign in the Voice referendum, people either love her or hate her with not much in between. But controversy has not stopped the relentless march of this 43-year-old Warlpiri-Celtic woman through the ranks of conservative politics. Good luck trying to pigeonhole her. She is a revisionist, a radical and a conservative all at once. She says things that no other politician would dream of saying. She has a vision of Indigenous Australia that up-ends decades of conventional progressive wisdom. She repudiates the narrative of invasion trauma and states that Aboriginal domestic violence is ingrained in traditional culture and must be tackled as such. You could hear a pin drop around the country last year when told the National Press Club she believed colonisation has had a “positive” impact on Indigenous Australians because “we’ve got running water, we’ve got readily available food. I mean, everything that my grandfather had was because of the whitefellas”.

No prominent Indigenous leader has ever said such a thing. Fellow Indigenous leader Marcia Langton has declared her a “gothic personality” with a “dangerous agenda”. Langton once said she suspected Price was “useful coloured help”, brought in by “conservative outfits” to “help in rescuing... [their] racist image”.

Price calls Langton’s claim insulting, and is unrepentant. “What Marcia did was highlight one of the issues that drove me into politics in the first place: the widespread and deeply entrenched view that Aboriginal people all have to think the same way – that we’re not entitled to our own opinion, and if for some reason we don’t subscribe to the view that we’re all victims of colonisation, then we are to be pilloried,” she says.

If the upcoming election falls the way of the Coalition, Price will be the Minister for Indigenous Affairs in the Dutton Government, and the Minister for Government Efficiency, a newly created post – and potential flashpoint – that could afford her sweeping powers to overhaul the bureaucracy. It would mean Australian policy towards First Nations people, and potentially Canberra, will never be the same again.

Thump.

My head.

Blood. Warm and sticky. Trickles down my face.

F..king bastard.

My head.

My f..king head.

It hurts so much.

Run, Jacinta, run.

For your f..king life.

Never look back.

So starts Price’s new memoir Matters of the Heart. She was in her mid-twenties, a divorced single mum with three young boys living in Alice Springs, when she met a non-Indigenous man named Jai. “This relationship set off major alarm bells from day one, but I didn’t hear them, or perhaps I didn’t want to hear them. I was vulnerable, I had money in the bank, and I was looking for love. I was an easy target for a charlatan. Come in, spinner,” she writes.

She caught Jai cheating on her and when she confronted him, he bashed her while she was in her bed, tried to choke her and rape her and then smashed her in the head with a bedside light before she bolted out the door and into the street with blood flowing from her head. Jai was eventually charged with aggravated assault. For Price, who had grown up with “stories of rape, domestic violence and the murder of young girls and women everywhere”, the fact that she had narrowly escaped from such brutality shook her to the core.

“I went through a stage where I just felt such an emptiness. My self-esteem was completely shattered. Everything that I thought about what it meant to be a good human being, a good wife, a good partner and seeing the good in others was just shredded,” she says as she looks out over the Tamworth hinterland.

But worse was to come. “It would be easy for me to gloss over this period, perhaps to briefly touch on it and move on, but there is no point in me telling my story if I’m not completely honest. And that means sharing the darkest period of my life. It’s a time I’m not proud of, but one that very much shaped who I am today.”

After her relationship with Jai, Price and her former first husband, Simon Castle, a childhood sweetheart with whom she had three young boys, agreed on a custody arrangement of two weeks on and two weeks off. But Price says she fell into a “Jekyll and Hyde” life of being a responsible mum for two weeks and then hitting the party scene for the next two. “Without the boys buzzing around, the house was uncomfortably quiet and lonely. When they were babies I had craved time to myself, but now I didn’t like being alone and made sure there was always someone around.” she writes.

“Sometimes we’d go out to the pub and have enough drinks to take the edge off my creeping anxiety – and when the weekends arrived, with no kids to look after, the girls and I hit the town. I’d never had this much freedom in my life, and I was making up for lost time. I could go anywhere and do anything I liked without the responsibility of mouths to feed, clothes to wash and kids to bathe. On the dance floor, I lost myself – I felt like I was 17 again.”

Price says that for “a few brief hours, alcohol magically washed away my fears and the persistent feelings of failure and self-loathing. I fell under its spell regularly.”

“Pills washed down with a lot of alcohol kickstarted benders that ended some time on Sunday afternoon, leaving me just enough time to get cleaned up and sobered up before fronting up to work on Monday. Some weekends my friends and I didn’t sleep at all,” she writes.

“At the time, I foolishly thought that the drugs like ecstasy were helping me shake off the darkness that constantly shadowed me. I revelled in the high that came from a tablet, but in truth each hit was contributing to a cycle of depression and anxiety, and each high was followed by a crushing low. I was caught in a dangerous cycle.

“I wanted to change. I hated who I’d become – I didn’t feel like myself and I wasn’t happy. With the support of my doctor, I entered a drug and alcohol rehab program, [which] involved intensive counselling, to identify and deal with the underlying emotions and feelings that were triggering my behaviour: my grief and feelings of failure after my marriage ended; the shock and fear I felt after Jai’s violent attacks; the loss of my identity and self-confidence.”

She says she is proud of how she came out of the spiral and reclaimed her life. But it made her reflect more on her childhood, her family and the scourge of domestic violence for all women. “It’s OK to be able to stand in front of the Australian people and to talk about your beliefs and how you think we can fix problems and that sort of thing. But it’s another thing to be able to say, ‘Look, I’ve been there. I’ve walked that road too’,” she says.

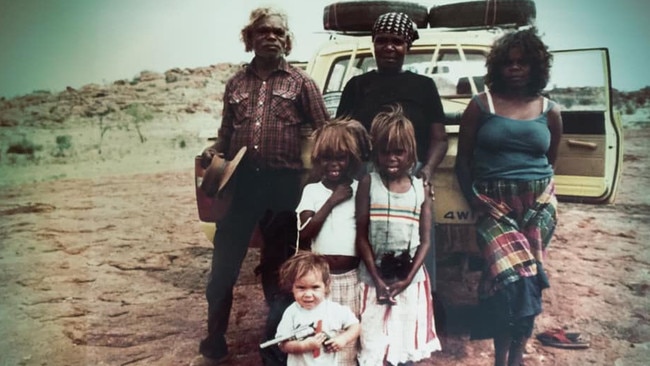

Although marked by the pain of losing her older brother, Linawu, to leukemia when he was just 10 years old, Price says she had a “wonderful” childhood growing up in Alice Springsand at her mother’s hometown of Yuendumu, 300km to the northwest. But she says that as she grew older she came to realise the darkness that lurked within her community and even within her own extended family.

Her mother, Bess Price, a Walpiri community leader and a former Country Liberal Party politician for the Northern Territory electorate of Stuart, gave birth to Linawu at age 13 and went to live with his father in Yuendumu who subjected her to alcohol-fuelled beatings. “She still has a scar on her chest from his teeth after one attack, and lasting damage to one foot from when he used a house brick to crush her toes,” her daughter writes. Bess Price became an early critic of the high levels of violence and sexual abuse in Indigenous communities and later married Jacinta’s father, Dave, a white teacher from Newcastle, of Irish background from a staunch Catholic family. “I have many happy early memories of times at Yuendumu,” Price recalls. “As a child I was introduced to the wonderful aspects of our traditional culture and customs, and wrapped up in the love of a big, often crazy, Aboriginal family. But I was also acutely aware that Yuendumu had a dark side.

“I can’t pinpoint exactly when I first became aware of the violence or the drinking, because they were just always there: aunties would stay over at Mum and Dad’s to escape abusive husbands, or there’d be chatter about young girls being sent off to older men. On nights we stayed at Yuendumu, we heard the screams and saw the fights – and then we’d wake up the next morning and get on with life.”

Price also can’t pinpoint exactly when these experiences led her to openly question aspects of traditional culture. But there are clear markers. One was when she heard the story of her aunt Marion, who, on a Sunday in 1982, was seen getting into a car at Yuendumu with five men, each well known in that community. Marion, who was 14, was never seen again. The men in Yuendumu refused to speak and no charges were ever laid. “Marion had become yet another victim of a culture of silence that has protected perpetrators in Indigenous communities for decades,” writes Price.

Another of her aunts was repeatedly raped by an older man with such violence that she could never have children. In 2014 another aunt, her mother’s last surviving sister, Rosalie, was stabbed to death by another woman at a Warlpiri camp near Katherine.

The more Price looked at these tragedies, the more she came to believe that communities needed to bear more responsibility for their own behaviour and not simply blame white colonisation or other outside forces. “It’s important to understand the cultural laws and norms that enabled the disappearances [like Marion], because some of them are still in force today,” Price writes. “Warlpiri culture … is deeply patriarchal. Men are considered superior to women, occupying a privileged position in society, and the interests of the collective outweigh the rights of the individual. These principles, which are thousands of years old, are still being used to oppress women now.”

Despite the trailblazing example of her mother, Price says she never seriously considered a career in politics while growing up. At school in Alice Springs she played music and flirted with the idea of becoming a police officer, but all of her plans were upended when, in year 12, she fell pregnant to her then boyfriend Simon; the due date was the day of her year 12 formal. Almost a year later the new parents got married and moved out together; Price worked at a local gallery, while Simon worked as a bricklayer. By June 2003 Price had given birth to her third boy. She had just turned 22. But the marriage soon began to fray, and in 2006 she and Simon separated. She moved out and took the children with her.

“Becoming a single mum to three boys is by far the hardest thing I’ve ever done,” she writes. “I really hadn’t anticipated how deeply the loss of my marriage would affect me. Financially, it was crushing: I was still contributing to a mortgage on a home I didn’t live in, while trying to scrape together every dollar to find a place to live and support myself and my boys.”

Price’s next chapter was her darkest. She and the boys moved briefly to Darwin with her new boyfriend Jai. After Jai bashed her, she broke up with him and they returned to Alice where she fell into drug and booze fuelled depression.

Price was determined to rebuild her life in Alice, working at an arts organisation that promoted Aboriginal artists. She started playing AFL and formed a band with friends called Catch The Fly. (In 2013 she released an album, Dry River, produced by Bill Chambers, father of country singer Kasey Chambers.) She then got a job with Imparja Television as a co-host for their children’s show Yamba’s Playtime, a hugely popular program across central Australia about the adventures of Yamba the giant red honey ant. “Landing that role was a dream come true for me, and the beginning of one of the happiest periods of my life,” she says.

Price had another stroke of good luck at that time when she bumped into a Scottish man in Alice Springs Hospital, where both were taking their sick kids. They chatted briefly, then bumped into each other in the street a few months later. Then one day Price walked into a popular Alice Springs music bar with some friends without knowing that that same Scotsman, a musician named Colin Lillie, was playing there that night. “At first I didn’t see Colin, but he saw me. He remembers me wearing knee-high brown leather boots over my jeans, and a camel-coloured winter jacket. My hair was long and loosely curled. He turned to his mate and asked, ‘Who’s that woman?’”

“That’s Jacinta Price – she’s on TV and she’s famous,” he was told. Colin absolutely swears that he turned to his mate and declared, “I’m going to marry her.”

They began dating, cautiously at first, as both were still stitching their lives back together. Colin, now a successful musician, was the son of a domineering, alcoholic father from a remote village in Scotland. At the time he met Price he was three years sober and father to a four-year-old son.

“On the face of it, you might not expect an Aboriginal woman from the Australian Outback and a bus driver’s son from the north of Scotland to have too much in common,” says Price, who has previously been reluctant to talk in detail about the relationship. “As it turned out, we had both grown up surrounded by drunkenness and violence, in communities clouded by hopelessness and despair.”

They moved in together, with her three children and his one, and in January 2023 – 10 months before the Voice referendum – they held a secret wedding on the beach at Queensland’s Stradbroke Island with their kids and a handful of friends. “Our wedding was small, intimate and absolutely perfect,” she recalls. “I was so proud to be Mrs Lillie.”

Price says her pathway into politics was unplannedand was never on her “to-do list”. “[But] with an example like Mum in my own family, maybe I was always going to end up in politics,” she says. She was already forming strong political views without fully realising it. She remembers being hugely relieved in 2007 when, two months after the Little Children Are Sacred report was published describing the rape and murder of children, including babies, in Indigenous communities the Howard Government introduced the Intervention, restricting alcohol and pornography in remote communities. “The usual critics hated the Intervention and decried it as racist, but the silent majority of us in Alice Springs were bloody grateful that someone was actually doing something,” she recalls.

Yet it was not until 2015 that friends persuaded Price to dip her toe into politics, by running for, and winning, a seat on the Alice Springs Town Council. Shortly afterwards, in early 2016, she penned that incendiary social media post about Australia Day which changed everything. “After 24 hours, my post had been read by more than 130,000 people and had been shared more than 10,000 times,” she recalls. “I’d unwittingly tapped into something important, and without any warning it changed my life: suddenly the media was contacting me and I was inundated with requests to speak. In an instant, I had a national platform.”

Price was in hot demand because, in her own words, there “weren’t too many black voices in the media providing a different view to that offered by the city-based academic activists”.

She says being a victim of domestic violence made her more determined to speak out. “I thought, ‘Stuff it, I’m not going to remain silent and I don’t care who I piss off in doing so’.”

She believes too many Indigenous leaders seek to blame others for the problems of Aboriginal Australians rather than looking in their own communities. “We’ve got a lot of crap that needs cleaning up in our own backyards,” she says. “Our children experience the highest rates of sexual abuse, our women suffer the highest rates of domestic and family violence, and yet if I criticise this some Indigenous people say, ‘Oh, you’re making us look bad’ or ‘You’re emboldening racists.’ We’ve got to get off our backsides and actually support the victims and hold people accountable for their crimes.”

Marcia Langton disagrees with Price’s claims, saying it is “self-serving” to point the finger at Indigenous communities when domestic violence is endemic and spread across society. “With more than 100 women of all cultural backgrounds murdered in Australia in the last 18 months, the women of Australia deserve better than her self-serving, attention-seeking campaign,” Langton says. “The evidence shows that this violence is universal and cannot be explained by her simple theory.”

However, as Price points out in her book, “The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare reports that in 2022-23, Indigenous women were 34 times more likely to be hospitalised as a result of domestic violence than non-Indigenous women.”

Price decided that if she was going to effect meaningful change she needed to be in Canberra. In early 2018 she was preselected as the Country Liberal Party candidate for the seat of Lingiari but lost in 2019 to the Labor incumbent Warren Snowdon. Two years later she won preselection as the CLP’s candidate for the Senate, and at the 2022 election she became a Senator for the Northern Territory.

Dressed in a cream, soft plum and dusty pink fabric designed by artist Eunice Napanangka Jack from Ikuntji Artists – the first art centre established by women in the Western Desert Art movement – Price used her maiden speech to deliberately rile black-armband activists by saying she “always was and always will be … a proud Australian”. She also railed against what she described as empty symbolic gestures, like the Walk for Reconciliation across Sydney Harbour Bridge or the endless Welcome to Country rituals.

Subsequently, she emerged as the most high-profile opponent of the Indigenous Voice to Parliament, which Anthony Albanese had proposed during the election campaign. “The Voice, as I saw it, was just one more symbolic gesture – a gesture Indigenous people didn’t need, and one that could actually do us harm,” she writes. “A single ‘Voice’ representing Indigenous people was insulting.”

Her argument was that it would do nothing to actually improve the lives of Indigenous people, and it divided people by race. In any case, she said, it was “plain wrong” to suggest Indigenous Australians did not already have a voice. “When I joined the Senate in 2022, I was one of 11 Indigenous voices in the federal parliament, a record number. Together we made up 4.8 per cent of federal parliamentarians, at a time when Indigenous people were 3.2 per cent of the Australian population.”

Price soon became the public face of the No vote along with another Indigenous leader, Warren Mundine, and reveals in her book how she approached the powerful Advance lobby group campaign director, Stephen Doyle, and executive director, Matthew Sheahan, to join the anti-Voice campaign.

But it was a brutal arena to be a gladiator in. Price was detested by the Left and especially by many other Indigenous leaders who saw her as a traitor to her people. “The campaigning was sometimes nasty, even vicious, and some of the attacks on me were deeply personal,” she recalls. “At one point I had to change my phone because my number had been publicly exposed, and the campaign team were constantly intercepting vile, hateful and physically threatening emails, letters and social media comments, trying to protect me from the worst of them.” Soon Price needed an Australian Federal Police security detail wherever she went.

“For every person who said something nasty to me publicly, there were plenty more doing it online and on social media, hiding behind fake names. My parents became a target, too: their home was vandalised, pelted with eggs and paint, bottles were smashed across their driveway and terrible things were said to them.

“And then there were the very public, very personal attacks by people like Noel Pearson, who suggested I was caught up in a ‘tragic redneck celebrity vortex’, and Marcia Langton, who said that if you started pulling arguments for the No case apart, you’d always get down to ‘base racism’, or ‘just sheer stupidity’.

“I took great exception to that. I’ve always believed that Australians have an acute bullshit barometer: we can sniff it in the wind, and we don’t like it. Australians are not racist, and we are not a racist country,” writes Price.

Former prime minister John Howard says he admired the way Price tackled the Voice debate. “Hers was not the language of complaint,” he writes in a foreword to her memoir. “She did not accuse her fellow Australians of inherent discrimination and bigotry … Rather, she appealed to the common aspiration of all decent-minded people to remove the barriers and dissolve the differences which unfairly impede so many of our Indigenous brothers and sisters.

“[Her] story is an optimistic and positive one. It is the story of a person who … has worked, lived and married across racial boundaries. This is of course the antithesis of how life in Australia is depicted by those who argue that the history of this country is steeped in racism and discrimination against minorities.”

Price says when the Voice referendum results came in, she felt relief and gratitude above all. She says she just wanted life to go back to normal. “But life wasn’t the same, and it will never be the same again,” she says. “My family had front-row seats to an extraordinary chapter in our nation’s history, during which we saw the very best and the very worst of humanity.”

The morning after the referendum result, Price says that she, Colin and the boys had breakfast at a coffee shop in Brisbane, where she saw a group of people at a nearby table whispering and staring at her. Then, to her amazement, they stood up and clapped. It was a reaffirming moment after such a brutal campaign. (She says she was quickly brought back to Earth by her boys: “Mum, you might have saved Australia … but can I have fifty bucks?”)

It was months later, at the most unexpected time, when the emotional cost of being the face of the most divisive referendum in a generation finally caught up with her. Price was in Edinburgh, Scotland, driving down the city’s famed Royal Mile, when she suddenly felt the heaviness in her chest lift. “[It was] an almighty physical and emotional release. Tears. Floods of them. The pressure of the last 12 months of the Voice, the build-up of anger, sadness and despair, and my relief at the result all rushed to the surface from deep within, and I couldn’t stop crying.

“It was in that moment, in the car with Colin, crying my eyes out, in the silence and serenity of Edinburgh, that I found myself again,” she says. “I was just Jacinta.”

So why write a memoir now, on the eve of an election? She smiles and says her aim is to give “Australians more of an understanding as to why I am passionate about the issues I have advocated for. I wanted to give a more personal perspective, you know, Jacinta the human, the mother, the daughter, the sister, the child, as opposed to the politician.”

Price uses the book to make a series of promises, saying she will “support Australians on the basis of need, not race”.

“Aboriginal communities need to reject outdated beliefs and cultural practices too, leaving the entrenched misogyny of the past behind. It’s time that we stopped treating women and girls as possessions to be traded,” she writes. “It’s also high time we stopped romanticising ‘the world’s oldest living culture’, and work out how our culture can adapt to a changing world, not just to survive but to thrive.”

Price has pledged to call for a royal commission into the sexual abuse and domestic and family violence suffered by Aboriginal women. “We must understand the full truth of what is happening in our communities, and what has happened in our communities. We must find the courage of our voices, no more silence.”

This memoir is clearly aimed at underpinning the next chapter in Price’s political journey. If the Coalition wins government, she’ll be a cabinet minister by mid-year. But many wonder whether an even higher office one day beckons. Does Price see herself, like some of her backers do, as a potential prime minister?

“Yeah, that’s a big call,” she says. “I mean, I’m absolutely grateful and humbled by the fact that a lot of Australians … you know, I hear that on a regular basis, but I’m like, you know, there’s a lot involved with becoming the prime minister. And do I really want the top job? I mean, my life already doesn’t really belong to me.”

She says her only aim right now is to make the changes that will improve the lives of Indigenous Australians. “I’d say, ask me once I’ve achieved those, how I feel about that. Yeah, that’s what I’d say.”

Then she pauses before adding: “On the other hand, part of me is quite a spiritual thinker, and if I’m called to that [higher office], then I’m obliged. Yeah.”

Matters of the Heart by Jacinta Nampijinpa Price (HarperCollins) is out on Wednesday

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout