On the trail of a predator

HE knew the victims; he had their statements. But dark forces stood in the way of Detective Denis Ryan catching this paedophile priest.

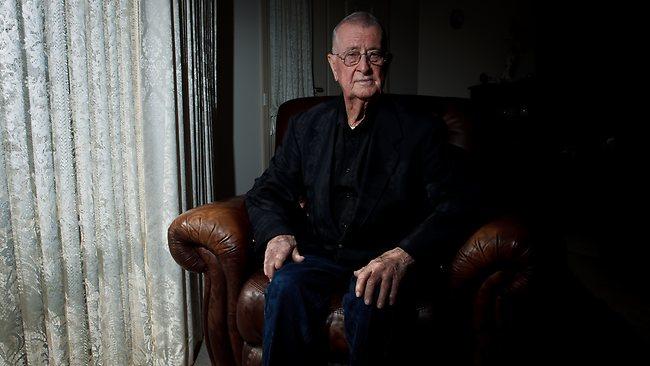

I AM Dinny Ryan and I have just turned 81. I'm a man of unwavering faith in my God, so I have to believe I was destined to clash with the paedophile priest, Monsignor John Day. Others will call it a coincidence. If that's the case, it was an extraordinary one.

I collided with Day twice. The first time was on the streets of St Kilda, in inner-city Melbourne, when I was in the company of two fellow uniform police officers. Day - drunk to the eyeballs, his cock out - was with a couple of well-known prostitutes from the area. That was in 1956. I was barely out of the academy. The second time was in 1971, when I was a detective stationed in Mildura, in north-west Victoria on the Murray River. I conducted an investigation into Day's paedophilia. I found witnesses and obtained statements from numerous victims. I had him banged to rights. On both occasions, Day walked away.

John Michael Joseph Day was already a priest when I was born. He had made his way through the Corpus Christi College in Werribee, a shining edifice for the future priesthood. At the Victorian parliamentary inquiry into child sex abuse, Professor Des Cahill from RMIT prepared a submission that revealed that, of the 378 priests who graduated from Corpus Christi between 1940 and 1966, 14 have been convicted of child sexual abuse and four more, who have since gone to meet their God, were also abusers. By my rough arithmetic that's one in 20 about 40 times the number of sex offenders in the general community.

Day isn't included in these statistics because he graduated from Corpus Christi in 1927. He was assigned to his first parish, Colac, near Geelong, in 1936, having spent the preceding years as a young priest at Ballarat East. After Colac, he was sent to Ararat, then Horsham, Beech Forest and Apollo Bay before being dispatched to Mildura. There he spent 15 years, standing over the community, helping himself to parishioners' money, committing complex fraud and wantonly raping children.

While I wouldn't learn of his crimes until 1971, I have since discovered that Day was an active paedophile throughout most, if not all, of his priestly existence. He preyed on hundreds of victims and committed thousands of offences. That a man, let alone a priest and, in Day's case, a monsignor (a title granted by the Pope) who held the second most senior position within the diocese could commit crimes of such violence against children challenged my faith and cost me the job I loved.

Day believed that he had been ordained by a superior power to be the supervisor of our morals, but he was a man without the first semblance of morality. He may have joined the Church despite his unconstrained sexual perversions, or perhaps because of them. What he knew implicitly was that the authority that came with being a priest verged on the absolute; his crimes against children were unlikely to be exposed.

Fred Russell was a detective sergeant in the early 1960s. He would go on to be the head of the CIB in Victoria in the late 1970s. He was a suave man, tall and powerfully built, with a head of thick brown hair that he kept slicked back and parted neatly on the left. He was of more senior rank than me but we regarded each other as friends. He also knew, as other senior coppers who were Catholics knew, that I was a Catholic, too. One afternoon I was part of a group of detectives enjoying a beer at a West Melbourne hotel when Fred pulled me aside. He and I wandered to a dark corner of the pub before he stopped and scanned the room. "Look, Dinny, what I'm about to tell you is in the strictest confidence." I nodded my consent.

"I don't know if you know this but there is a group of us who, at the request of the Cathedral, look into instances where priests have been charged with offences to see if we can have these matters dropped or dismissed so the Church's good name will not be brought into disrepute." Fred paused and looked at me intently before continuing with his spiel. "We know your strong belief. We'd like to invite you to join us. You should give this some consideration and let me know as soon as you can."

No names were mentioned, but it was clear that the requests had come from the highest echelons of the Catholic Church in Melbourne. I was genuinely taken aback. I met up with Fred a couple of days later and told him I wasn't interested in joining this shadowy group. He took my rejection in a matter-of-fact way. He certainly didn't seem put out. "Oh, well," he said. "Fair enough. It's your decision."

He had not told me who else was in this group. But they, like Fred, took their orders, in part at least, from St Patrick's Cathedral. These men suffered from a distorted sense of loyalty to the Church. And that misguided loyalty drove them to ignore their oath to the police force and to the people of Victoria they purported to serve.

I continued to practise my faith. I went to mass every Sunday at St Brigid's in Mordialloc, in Melbourne's south-east suburbs. The parish priest there, Father Jim English, was a decent man, a good priest with a boisterous sense of humour. One day he invited me up to the presbytery for a cup of coffee. I had expected nothing more than just another convivial chat, but in the middle of our conversation, Father Jim trailed off, paused and leaned forward in his chair. He looked at me with an earnestness that I had never seen on his face before. "Do you know that a priest was caught by the police down at Chelsea Beach exposing himself to young girls?"

He paused again. "Somehow this priest was not charged. Dinny, if something similar arises in the course of your duties, I want you to charge the offending priest. These things must stop."

As the winter chill fell on Mildura in 1971, I was at my desk on a Wednesday morning. The phone rang and I grabbed it. "It's John Howden here, Denis." Howden was the senior master at St Joseph's College. He had a reputation for being a very fine teacher and an asset to the school. "I need you to come up to the college," Howden told me. I was about to put the phone down when I heard Howden say, "Don't let Jim Barritt know I've called. I'll explain when you get here."

Barritt was the senior detective in Mildura and from early in my time in Mildura it was obvious to me that Barritt and Day were more than just friends. An avid member of the Catholic mafia, Barritt understood that the Church must be protected at all costs.

At St Joseph's College I knocked once on Howden's office door and it swung open immediately. Howden was standing there with a tall, elderly nun. He introduced her to me as Sister Pancratius, a teaching principal at the school. The sister offered a firm, curt greeting, standing as straight as the flagpole in the schoolyard. Howden and Sister Pancratius looked at each other before Howden cleared his throat and spoke. "The mother of one of our students has made a complaint that Monsignor John Day has indecently assaulted her daughter on a number of occasions." I was taken aback. I thought I knew Day's history as well as anyone. Prostitutes, yes. Did his depravity now extend to forcing himself upon schoolgirls?

Sister Pancratius waited for silence to fall before she spoke up. "I have known about Monsignor Day's behaviour for some time now. It runs contrary to my vows of silence to say this to you, and I will never repeat what I have said from this moment forward." There was a sad resolve in her words. "I am pleased to meet you, Detective Ryan," the sister said, and with that she walked past me and out of Howden's office, closing the door firmly behind her. Howden then told me the girl's name and recounted her allegations.

The following day, the young girl, a boarder at the school for a number of years, provided me with a statement alleging that Day had fondled her breast when he took her for a drive in his car. She said that this had occurred on five separate occasions. She had been 12 years of age when these offences occurred. Both mother and daughter confirmed they had reported these incidents to Sister Euphemia, a nun and teacher at the school, shortly after they had occurred. The daughter also told me a story she had heard from one of her classmates. Day had insinuated himself on the girl on the drive home from Melbourne.

The next day I obtained a statement from this girl, who was in her leaving year at school at the time. She alleged that Day had indecently assaulted her when she was in grade six at Sacred Heart. I didn't have enough to charge Day with at that time; the statements from the girls were uncorroborated. I needed to establish Day's pattern of behaviour. It was time to do a bit of digging into the monsignor.

Over the next couple of weeks I took statements from more of Day's victims. There was a certain ease to the investigation. Each victim gave me another name, and that person would give me another. One boy had been assaulted and raped in 1957. Another victim, a boy of 15, had been sexually assaulted by Day in 1970. Thirteen years. Five confirmed victims. Numerous counts of indecent assault, gross indecency and buggery.

The information flowed from the victims in their statements and records of interview. Other victims, other leads for me to pursue, were mentioned. I kept dwelling on what Howden had told me: "Avoid Barritt at all costs." My senior officer. My boss. I always thought he was as useless as pockets on a singlet but keeping him out of the picture - due to his friendship with Day - had a darker subtext. It was a rolled-gold certainty that Barritt would have stymied my investigation. Howden understood it. I knew it, too. The question was, why would he?

My boss was Day's protector. Barritt's mafia was designed on an equilateral triangular structure with Day at the top, Barritt on the right-hand vertex below and, opposite, Joe Kearney, the clerk of the courts, the most senior officer of the court in Mildura.

What did Barritt know of Day's perversions? What did Kearney know? They'd have to have been a couple of blind Freddies, and deaf and dumb as well, not to know.

I was a month into the investigation when I made up my mind to approach the most senior officer in the district - Superintendent Jack McPartland, who was based at Swan Hill. McPartland was a devout Catholic, but he was 222km and a virtual world away from the cloying atmosphere in Mildura driven by Barritt, Day and Kearney. I expected Jack to offer his support and guide me through the investigation. I rang him up and told him where my inquiry into Day had taken me. "I've got five statements from victims alleging that Monsignor Day has committed numerous acts of sexual assault, gross indecency and attempted buggery," I said.

I expected a pause, a moment of silence while McPartland reflected on the best way to proceed, but he fired back without hesitation: "I want you to give these statements to Inspector Irwin straight away and to cease any further inquiries. You are no longer involved in this investigation."

"But ... but ... what you're asking me to do will effectively destroy this investigation," I blurted out. "I'm going to tell you something now, Detective Ryan, and you're not going to like it. I'm a Superintendent and you're a nobody. Do as you're f..king told."

McPartland slammed the phone down in my ear. I sat at my desk, bewildered. I was so angry I could barely think. I took some deep breaths and let my fury subside.

I did as I was told - well, overtly at least. I handed over the five statements I had obtained to Inspector Alby Irwin, the senior uniform officer at Mildura. I could tell Irwin had been given a heads-up. He took the statements without a word, and then he just looked up at me for a moment before returning to his paperwork. It was obvious that this inquiry was headed for the dustbin. I had followed orders, but by the time I left Irwin's office I'd made another decision. I wasn't going to drop this, no matter who gave the order.

Officially, I was off the case. Barritt had ordered me onto divisional duties with the uniform boys the police equivalent of being sent to Coventry. Day denied everything, as I had expected. Irwin wrote a report in which he concluded: "It is my recommendation that no further police action be taken in this matter." After Irwin interviewed Day, I handed him statements from two further victims, young boys who both alleged Day had indecently assaulted them and subjected them to acts of gross indecency while they were at St Joseph's. Irwin snatched them out of my hand like I'd handed him yesterday's sandwiches.

By now Mildura was abuzz with rumour and gossip. The Catholics were divided almost straight down the line. One half supported me, the other half would have been happy to see me burnt at the stake as a heretic. It has to be remembered that at that time no priest had been convicted of child sex offences in Victoria or even in Australia, as far as I can tell. What I did know was that I had a raving child sex offender who happened to be a monsignor in the Roman Catholic Church, and no one in the Church or the police force seemed to give two hoots about it.

Some people wonder why I didn't walk away from the Roman Catholic Church. My faith was unshakable. I will remain a Roman Catholic until the day I die.

I wasn't going to let any of this bugger up my Christmas of 1971. Red Cliffs Church was a haven; in my six years attending mass at the church I'd never seen Day there. My wife Jean and boys Michael, Gavin and Anthony were sitting with me in the pews. We saw Martin, our second eldest, who was one of the altar boys, pass by in his red smock as the procession made its way to the altar. The Red Cliffs priest, Father Anthony Del Bollo, was next, and behind him was Day in his full monsignor's regalia, looking pompous and arrogant. As the congregation started to sit, I grabbed Jean's attention. "Jean, you take the three boys to the side door and wait for me."

She nodded, and started to lead the boys to the closest exit. I strode up to Martin at the altar. " Martin, go and get changed into your normal clothes. I'll wait for you here." Martin moved off straight away. I stood at the altar, waiting. The murmurs in the church grew louder as every second passed. I turned and glared at Day. He returned my stare with a look of shock and anger. "You dirty bastard. You think I'm going to let you anywhere near my children?" Day didn't say a word and returned his eyes to the congregation, attempting his most beneficent look, but I could tell he was rattled.

Martin appeared in his civvies a minute or two later. I grabbed his hand and walked towards Jean and the other three boys, who remained steadfast at the door. We got into the car and drove straight to Sacred Heart at Mildura, where we attended mass, knowing there was no likelihood of seeing Day there. Later we saw Day driving his car, a late-model Ford Fairlane, the other way along Eleventh Street. I don't know if he saw me. If he did, he didn't let on, but his hands were clenched tightly on the steering wheel and he had a look of impotent rage on his face. That was the last time I saw Day, but I would be dealing with ugly memories of him, his rape of children and his bloated sense of entitlement and authority for many more years.

By the end of January 1972 I had interviewed 12 of Day's victims. They all provided statements alleging that the priest had raped and indecently assaulted them. I hadn't touched on Day's time at Colac, Apollo Bay, Beech Forest, Horsham or Ararat. The 12 victims I'd found - altar boys, gymnasts and boys and girls at Sacred Heart Primary School and St Joseph's College - had all been children in Mildura. I could have found 100 victims there, maybe more.

At mass on Sunday, January 30, 1972, Monsignor Day informed the congregation that he had offered his resignation to Bishop Mulkearns. It had been accepted, and Day would be leaving the parish within days. He had outlived his welcome in Mildura but he was off the hook. He was driving down to Melbourne for a few weeks before heading overseas. He'd been given a world tour for his crimes - a trip to Chicago followed by a stint in Portugal for "counselling". All expenses paid.

When all the fuss died down he'd head back to Victoria, where he'd be sent to a new parish. Life for a disgraced priest wasn't too bad after all.

* Day died in 1978. He was never charged with any offence

Edited extract from Unholy Trinity: the hunt for the paedophile priest Monsignor John Day, by Denis Ryan and Peter Hoysted, $29.95 (Allen & Unwin), out Wednesday