Nothing plain about airline food

Airline food has gone from simply sating appetites to countering the impact of flight on the body. You’ll never look at your in-flight meal the same way again.

I step into an airlock-like compartment and the doors close behind me. Scores of chrome nozzles engage, blowing away stray fibres and hairs that I may have brought in with me. It’s a distinctly sci-fi moment, and by far the most dramatic entrance to a kitchen I’ve ever made. On the edge of Singapore’s Changi Airport, the SATS catering facility looks very much like any other industrial building dotting the perimeter. But here my attitude to airline food will be forever altered.

That small tray is an element of air travel that many of us love to hate. After the sensory assault of the airport, all I want is to be sated and soothed. A Bloody Mary, a half-decent movie and a small but tasty meal – just enough to level me out. It’s perhaps why for many of us, what lies beneath the foil matters.

Airlines are upping the ante on inflight hospitality – what chef/restaurateur Neil Perry, now into his 22nd year on Qantas’s payroll, describes as “fighting for savvy customers”. Even in economy on one of the better airlines, chances are you’ve noticed an improvement in the food. More thought and scientific tinkering has been put into it than you’d imagine.

With his well-trimmed moustache and Aussie accent, Rick Stephen cuts a dash. He’s the Director of Kitchens for this vast Singapore facility, with its dry stores and freezers storeys high, kitchen after kitchen, butcheries, halal sections and rooms dedicated to filleting fish or peeling prawns. The place hums with efficiency and the beep beep beep of carts in wide corridors. It’s a large, well-ordered machine of a place, full of conveyor belts, ingenious kit and people – lots of people.

Dotted around the airport perimeter are a handful of SATS centres servicing other airlines – this one is just for Singapore Airlines. One centre can produce 80,000 meals a day. I spy an omelette station, where a large hypnotic turntable with 15 inbuilt hotplates rotates, an industrial hose squirting a set amount of whisked egg into pans tended by three cooks with spatulas. The mysteries of scale, and the task of feeding palatable food to tens of thousands, start to unfold.

I’m shown the satay station – a long grill piled with hot coals, where 15,000 of Singapore Airlines’ signature satay sticks are cooked every day. And at Casserole Assembly, dozens of benches stretch out with rows and rows of trays being filled methodically. There’s the “European kitchen”, the “Asian kitchen”. We enter the “Premium kitchen” where a brigade of chefs works under a French head chef. Every leading carrier has a culinary relationship with a focus on the pointy end, Business and First classes. Qantas has Perry, Virgin has Luke Mangan and Singapore Airlines has the International Culinary Panel (ICP) comprising eight top international chefs including Matt Moran, the Sydney-based chef/restaurateur who has developed more than 750 dishes for Singapore Airlines in the past 15 years.

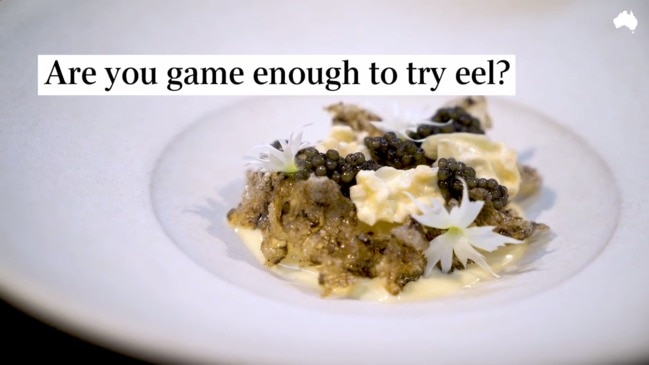

Up to 24 hours before their flight, Singapore Airlines customers can select their meals, many devised by the ICP chefs: a classic lobster thermidor with buttered asparagus, roast rack of lamb, grilled eel or satay sticks. Stephen dispels another myth: that airline food has to be a concoction of packets and powders. His kitchens produce 1200 litres of fresh chicken and veal stock from bones, daily.

The airline’s Global Food & Beverage Director, Antony McNeil, says that increasingly, menus are being filtered down to Premium Economy in a battle for differentiation in the market. And in development, chefs do more than rubber-stamp dishes stipulated by the airline, as I’d suspected. “Chefs like Matt Moran will provide signature dishes from their restaurants,” he says. “But they’ll also present, say, 50 dishes on paper, and of that presentation we may choose 12 to 15 items for First, Business and in some cases Premium Economy cabins.”

Chefs like Moran with portfolios of restaurants want to be sure they’re well represented at 30,000 feet, and this is where science comes in. Dishes will be affected not just by the need to refrigerate and reheat for service, but by altitude and pressurised cabins, which dull the senses of taste and smell. In the past, the simple answer was to use lashings of umami-rich ingredients such as soy and oyster sauce, cabbage and mushrooms to boost flavour.

While altitude is still a consideration (SATS uses a simulated cabin – really a pressure chamber – for taste testing), it’s less so with the advent of new aircraft, says McNeil: the A350, A380 and 787 cabin environments have better pressurisation and humidity. Perry is of the same opinion: “Some airlines hide behind [altitude as an excuse]; if it’s good on the ground it should be good in the air.”

Perry and his team of 12 development chefs embedded at Qantas develop 850 dishes a year, focused mainly on First and Business cabins as well as the lounge network. But in recent years they’ve been engaged in projects that go beyond the norm: sharpening Qantas’s edge in its push into ultra-long-haul flying. And here, food is playing a crucial role in scientists’ efforts to understand how to lessen the impact on the body of days in the air.

At the University of Sydney’s Charles Perkins Centre, sleep physicians, dietitians, lighting engineers and circadian clock experts are working with Qantas on a mission to mitigate jet lag, following the launch of its Perth to London direct route. The centre’s Professor Stephen Simpson says our circadian clock isn’t designed to go from one time zone to another in a single step: “You can only shift the circadian clock by about 90 minutes, at most, each day. So Perth to London takes perhaps six days.” Easing people towards the destination time zone in the most effective way is the goal.

“There isn’t a lot of data around the relationship between food and setting the body clock, but food can do it,” says Simpson. The body has a series of “clocks”, from the master clock in the brain to organs and even in single cells. Profoundly important in their communication with each other is melatonin, which is released from the pineal gland and is built from tryptophan, an amino acid found in the proteins we eat. If you can increase levels of tryptophan at the right time, you can change the levels of melatonin and serotonin – which affects sleep cycles – produced in the brain. “You can help people go to sleep at the right time if you feed them the right thing at the right time,” explains Simpson, “such that their body clock will be shifted in the right direction for their destination time zone.”

One way to get tryptophan into the brain is by consuming carbohydrates and tryptophan-rich foods together. “So we’re able to go to Neil and ask, ‘Can we design a menu which incorporates carbohydrate sources with protein sources that are relatively high in tryptophan?’” Perry duly responded by including more grains and pulses in dishes.

For the airline, this integrated research is merely basecamp in the quest to reach the summit that is Project Sunrise: direct routes from Sydney to London, and Sydney to New York. It’s clear that airline food has gone beyond merely sating appetites and even pleasing taste buds; now it’s an essential ingredient in making that round-the world flight bearable.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout