Mourning two giants of Kimberley culture, Donny Woolagoodja and Janet Oobagooma

They died within days of each other. But the extraordinary legacy of two giants of Kimberley culture, Donny Woolagoodja and Janet Oobagooma, lives on.

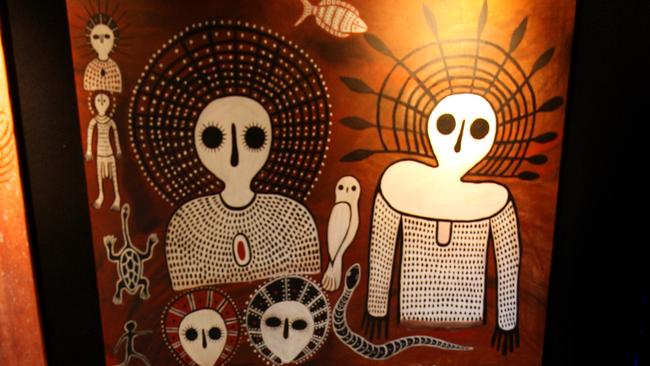

Inside an art gallery on a busy Sydney street, crowds were milling around the paintings of wide-eyed spirit figures from the far north-west of the Kimberley region. It was the final day of the ‘The Power of the Wandjina’ exhibition when a group of sports event organisers arrived, not to buy a painting but to look for an elusive image. The 2000 Sydney Olympic committee was on the hunt for a key element in the ‘Awakening’ section of the opening ceremony that would reflect the living culture of Australia’s First Nations people.

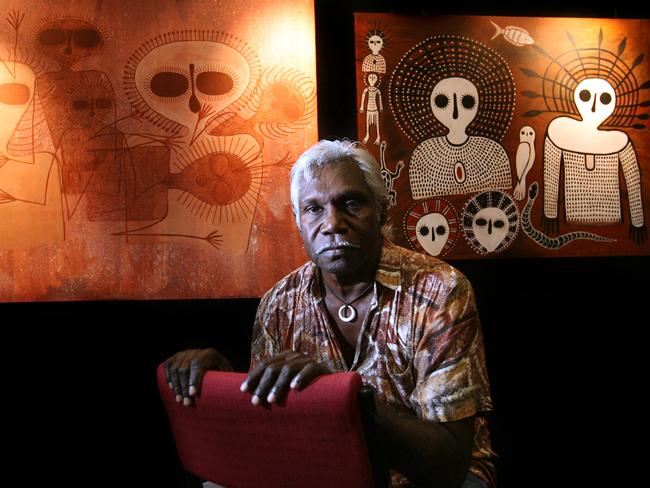

And there it was, a floating figure whose staring, mouthless face was framed by a dramatic headdress of cobweb-like complexity. It was Namaralay the creator, a Wandjina spirit that had been painted both on canvas and on a distant rock surface by artist Donny Woolagoodja. It would become the centrepiece image of the Olympic opening ceremony, an imposing figure that rose up over the main stadium like a benign, all-seeing parent.

“They looked at my painting and they liked it,” Woolagoodja recalled later. “I told them that I had to talk to other people before I could say yes. We had a meeting at Mowanjum when I came back from the exhibition and I got all the permissions from my Worrorra mob, the old people and the artists. They said ‘It is OK to do it.’” Woolagoodja described how his art was linked to Lalai, the Dreaming, and how the Wandjina were visible manifestations of supernatural beings who created the world before transforming themselves into paintings.

Woolagoodja flew to Sydney for the Olympic opening. He sat in the stands among Australians who had never heard of his Wanjina Wunggurr culture from the north-west Kimberley; nor had billions of people around the world who tuned in to watch.

“When he [Namaralay] came up in the opening ceremony, it made that emotion come out, like when you lose your own relation,” Woolagoodja said later. He vowed to make a trip back to the rock art site to “refresh” Namaralay, in the place where his great great grandfather Indamoi had painted an earlier image.

“When I cried for him I knew he was asking me to go back there and do that for him … That’s why I decided to go and paint him, because I’d showed him to the world. He drew me back to the cave.”

On September 18 last year, Woolagoodja – a quietly authoritative teacher, lawman, artist and author who for decades had been one of the key voices explaining the Wanjina Wunggurr world to an academic and wide audience – died at the age of 74. In a quirk of fate, only six days earlier another giant of Kimberley art and culture, Janet Oobagooma – with whom Woolagoodja had a deep, powerful connection – had died. “We mourn the passing of [these] two most senior Traditional Owners,” wrote Dr Martin Porr from the University of Western Australia’s Centre for Rock Art Research & Management. “We celebrate their lives and their invaluable contributions to the continuation of their community, as knowledge holders and advocates for their people.” He might have added that as a final act the two elders made a gift of knowledge to the world, shedding light on a mysterious German expedition and Kimberley paintings lodged in an institution across the globe.

Woolagoodja’s funeral ceremony in November, two months after his death, was crowded with mourners paying their respects; 14 pallbearers carried his casket. The funeral was “exhaustingly sad but respectfully completed,” says anthropologist Kim Doohan, who had worked closely with her friend of 30 years. In mid-December, Woolagoodja’s family took his remains to a remote coastal spot that he had once nominated as the place of his conception, “a whirlpool where two tides meet in the blue sea … I am that whirlpool”.

Woolagoodja’s nephew, Adrian Lane, says the global spotlight that fell on Kimberley culture in the wake of the Sydney Olympics had been predicted by senior men in the early ‘90s. “They said, ‘One day the world is going to come for us,’ and it did,” says Lane. “The Olympics showcased all that stuff, our world view, who we are and where this place is.”

Yet Woolagoodja had been a champion of his culture long before the Games came along. He made regular visits to significant sites, took part in recording the region’s fauna and flora, established tourism ventures, and painted artworks that were sought out by galleries and international collectors. After the Olympics, he designed a building for his community at Mowanjum, near Derby, as a place to display and sell the community’s art. A bird’s eye view of the roof reveals its shape as mimicking the outline of the watchful Wandjina.

“I think of Donny and Janet as the last of the tribesmen”

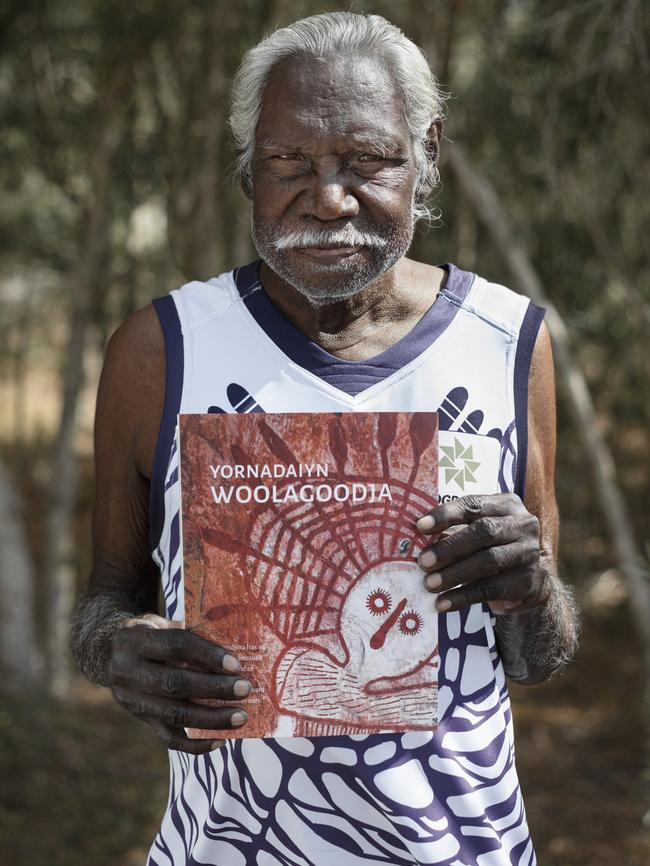

“We have a very rich culture which is still here today,” he wrote in his autobiography Yornadaiyn Woolagoodja. “We see it in the drawings on the rocks, the wildlife and the landscape in one of the most beautiful places in the world.”

“Donny was proud of everything he did for his people and the country,” says Lane, a marine park ranger who patrols long stretches of Kimberley coast. “He knew all along that things were never going to remain the same. He wanted to grow the Wandjina art, documenting our law and culture and history to the nation.”

Woolagoodja always referred to Janet Oobagooma in respectful cultural terms as “Mum”, even though she was only five and a half years his senior. Born in Broome on the day in 1942 when Japanese forces bombed the town, she was raised in the remote Presbyterian mission at Kunmunya 350km further north. As a child, she travelled by canoe around parts of the Buccaneer Archipelago, where 720 largely untouched islands dot the ocean like tiny green jewels. Periodically, she and her people were moved off their traditional lands and into towns or settlements by missionaries or government.

A deeply cultural woman, Oobagooma had learned from her old people about the complex traditions and languages of three groups – Worrorra, Wunambal and Ngarinyin. Her Indigenous belief system sat comfortably with being a committed Christian. “God is a Wandjina, all right?” she told the ABC’s Compass program in 2017, eyeballing the camera in a way that commanded attention. “A life giver, a food giver and a life saver – that’s how Aboriginal people believe, that Wandjina is sacred.”

Her penetrating gaze and frank opinions earned her a reputation as wise counsel on many issues, from native title to youth pastoral care and faith. “But she had a sharp wit, and she was good at one-liners,” says Francis Woolagoodja, Lane’s brother.

Francis invited Oobagooma along whenever they travelled by helicopter into remote country to carry out fire burning regimes. “After the wet season, you had to clean the leaves out of the caves before burning off, so they didn’t cause a fire inside and turn the walls black. I’d always take Janet back there so she could introduce us [to ancestors] and talk in the language of that place. She would always talk first before we went in.”

Francis and his brother were raised by both Oobagooma and “uncle” Woolagoodja after their mother died. They often found themselves spending weeks on boats, travelling with Woolagoodja as they navigated the remotest recesses of the Kimberley coast.

“When I was with him, I felt safe,” says Francis. “Even when we were in a five-metre dinghy in a storm at night. I never felt I had to worry about anything.” Lane recalls catching turtle and being shown how to cook it in the traditional way. “You chuck hot rocks inside the turtle, and you lay it down on coals so it becomes like a camp oven. I’d never seen it done properly.”

One trip involved revisiting a cave containing a rock art painting, which an archaeologist friend of Woolagoodja was keen to inspect for changes in the pigment’s colouring.

“I have an image of Donny sitting outside his tent that day, a crocodile laying on the beach about ten metres from him,” says Lane. “He’s like in another world, another aura. He said, ‘I don’t think we should go now [into the cave], it’s not a good time.’ “

The archaeologist was keen to go ahead, and began walking towards the cave with her five-year-old son. Before long she ran back in a panic – the boy had disappeared. “Just like he was going to the shops or something, Donny gets up and strolls up to the cave,” recalls Lane. Within a short time, he had found the little boy sitting under a tree.

“I think of Donny and Janet as the last of the tribesman, the people who were born in and walking that country,” says Lane. “There’s very few left.”

The knowledge of elders such as Woolagoodja and Oobagooma was crucial to gaining native title over their own lands under white law; one determination alone secured their native title rights over 16,000sq kms of land and almost 12,000sq kms of sea.

Meanwhile, the pair contributed to dozens of academic papers, films, videos and several books described as “our modern way to leave our Wanjina Wunggurr culture story to our children” – books like Keeping the Wandjina Fresh, Barddabardda Wodjenangorddee: We’re Telling All of You, and We Are Coming To See You.

Both Woolagoodja and Oobagooma had a hand in virtually every sentence of those written records, says Doohan. “We became a tool for them to tirelessly work out what was going to be important for their young people to have a sense of identity and continuity. Both Donny and Janet had a very strong sense that if you don’t know who you are and where you come from, you will be lost. And if you’re lost, you can’t function and you certainly can’t protect your country or yourself.”

The pair were also motivated by a sense of disquiet that, for too long, strangers had interpreted their culture and become “authorities” on their rock art. Oobagooma described her vexed feelings about it to an international conference in 2015. “Sometimes we hear about other people talking about our culture and we are worried about that because they do not know the real meaning of it,” she told them. “We are worried because they try to tell our young people and we do not want them to make a mistake.”

Yet late in life, and despite their misgivings about outsiders, Woolagoodja and Oobagooma chose to be part of an international project spanning two continents and nearly a century.

In 1938, a German artist visiting the remote Kimberley region asked an Aboriginal elder if she could sketch his portrait. It was Woolagoodja’s great-great-grandfather Indamoi – the man whose rock art inspired his descendant’s Olympic creation. The artist was part of a scientific party from the Frobenius Institute in Frankfurt, headed by pioneering social anthropologist Leo Frobenius. His teams of anthropologists and illustrators had recorded prehistoric rock art in Africa, Europe and the Middle East, and now it was Australia’s turn.

In a pre-war era when much of the Kimberley’s interior was still unmapped, Frobenius’s expeditioners spent several months interviewing Indigenous people and recording their culture. The task of two female artists was to record Kimberley rock art, especially the Wandjinas.

“They sat in front of the rock art, and reproduced it in a photographic way,” explains Porr, from UWA’s rock art centre. “They did the first systematic rock art recording in colour in Australia – paintings so accurate they were like photographs,” he says.

“They were quite respectful in a way that some anthropologists of that era were not”

German-born Porr, who migrated to Australia in 2008, had come across German-language references to the Frobenius expedition – and the vast collection of photographs, detailed recordings of mythology and art images, kept in Frankfurt. “So much detail came out of this specific time,” he says. “They were almost forensically looking at what happened back then, and they were quite respectful in a way that some anthropologists of that era were not.”

Doohan says she was astonished to learn about the Frobenius archive. “It was absolutely unbelievable. They had been archived but unseen for more than 80 years.” The expedition material needed to be translated, digitised and – importantly – repatriated in some form to the Kimberley. Doohan and Porr began to consult with Indigenous communities and their elders; plans were made to travel to Frankfurt to view the Frobenius material and a later archive from a 1955 expedition, held in Munich.

Both Woolagoodja and Oobagooma were invited, but didn’t feel they could make the long journey to Europe. Instead, they chose Leah Umbagai, Donny’s granddaughter, to travel with Doohan on their behalf. “We went to Germany about four or five times – Donny and Janet encouraged us to do it,” says Umbagai. “The paintings and the pictures of the old people blew me away – they got up close and personal with people I never got a chance to. And they held a lot of information that we don’t have. I wanted young people to see it because we have problems with kids not knowing about their culture. We wanted the material to come back to the Kimberley for people to talk about them.”

The project has turned into a gift of mutual goodwill across time. A digital repatriation project has emerged between the Frobenius Institute, the University of Western Australia and three coordinating partners, the Wilinggin, Wunambal Gaambera and Dambimangari Aboriginal Corporations.

An elaborate database, with English translations, is now digitally accessible to the relevant Aboriginal corporations. Groups of elders are able to correct or interpret historical accounts of their own flesh and blood.

“They’ve often said, ‘And here’s a bit more that you should know’,” observes Doohan. “Early on we started to relocate some important sites that we knew the expedition had been to. We went with Donny and Janet to those sites while they were still able, and we corrected the records. You’re standing at the spot and you’re saying to them, ‘Well, this is what we have from what the Germans observed … what do you reckon?’”

Did they object to the Germans’ forensic scrutiny? “No, although they did identify when things should be restricted [from viewing]. Janet never liked it but she didn’t dismiss everything they did as a result of that. She’d say, ‘Well, they only talked to [Aboriginal informants] once’, meaning that she strongly believed you couldn’t understand the meaning of things on a single investigation.”

Recently, the Frobenius Institute printed 150 art reproductions on sturdy material; two Frobenius researchers accompanied them to Australia.

“Each copy was to exact scale – if the rock art image was five metres across, the copy is five metres across,” says Porr. He hopes that the cross-cultural project “can integrate the archive in Germany to the projects the communities have already been working on.”

Members of some communities have already got a glimpse of the German collection, and more viewings are scheduled. Lillian Karadada says she enjoyed seeing the portraits of family members. “There was a photo of our grandfather with a young Jack Karadada, our father, and it is probably the only one which exists. That’s very special for us to see.”

Among the first to view the material was Donny Woolagoodja, as he sat surrounded by hung cloth images in a large shed in Derby. “He was overwhelmed by it, and wanted to take a photo with his phone,” recalls Lane. “Then he dropped it and it broke, which he took as a sign. Instead, he did a painting inspired by one of the German paintings. For me, to see the images made me feel like they were famous great people who had their spotlight in that world.”

Doohan sensed “a real gratitude” that the portraits had come into existence. “People were so moved, and they said things like, ‘I feel like I’ve got my ancestor here with me.’”

Lane sees it as an opportunity to inspire a new generation. “There’s a handful of boys and girls already lined up [as leaders], and Donny and Janet prepared them. We are trying to get kids on country, and this Frobenius stuff is really critical because we’re going back in time to instil the values of earlier leaders, linking the country with the people in those portraits.

“It’s adding layers of protection, to country that is part of us … It’s two-world stuff, like we’re part of the puzzle. We’re continuing something that goes back to the time of the Creation story. They were powerful people and it’s not for us to drop our guard.”

Umbagai says the elders’ accounts – both historical and those left by Woolagoodja and Oobagooma – make her more resolute, proud to speak out. “We feel like our voices are in the wind, we are whisperers. But they put themselves out there – they said, ‘We do exist, listen to what we say.’”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout