Little girl lost

A QUEENSLAND grandmother describes the "absolute horror" of child protection services, which are dealing with the nation's most forgotten kids.

The photographs she likes most are from the sections in her catalogued box marked: "Nicole: Baby" and "Nicole: Toddler". She hasn't taken any yet from the section marked: "Nicole: Adult".

Yvonne studies a small photo of her daughter, aged six. Toothy smile, 1978. Blue ribbons on well-brushed pigtails. Happier times, before Yvonne saw three generations of her family removed by state child safety departments.

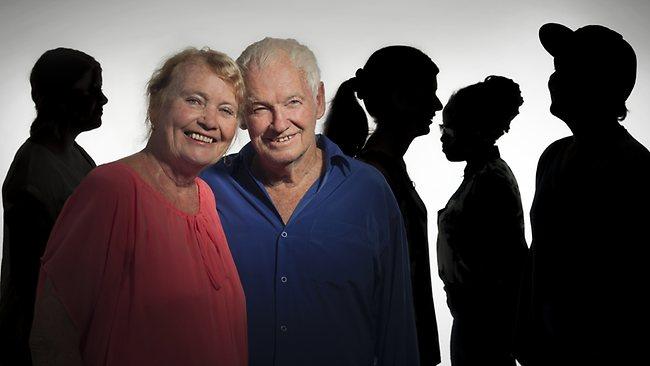

Yvonne is 62. She has short grey hair. She's a Queensland teacher with more than 20 years' experience. Somewhere there is pride in her face, dignity worn down over 27 years by fear, regret and, finally, loss. "If it's happening to three generations in the one family, doesn't that tell you there's something wrong with the system?" she asks.

Yvonne wants to use her real name but can't because her grandchildren - along with 8063 other Queensland children and 37,648 children across Australia are living in foster care or other out-of-home-care arrangements and their identities are protected by law. But that hasn't stopped her having a voice.

She hands over a statement she gave in private last year to former Family Court judge Tim Carmody, whose $9 million Queensland Child Protection Commission of Inquiry has until April 30 to resurrect a system Queensland Premier Campbell Newman says is failing. Then she hands over a story she has written about her 27-year journey through the child protection system. It's titled A Series of Unfortunate Events. It's the story of the bright, piano-playing girl with the blue-ribbon pigtails who grew into a rebel and a runaway who took full advantage of a single mum struggling to raise her and a younger brother (now an aircraft technician) in a working class regional town, while Yvonne worked a day job and studied to be a teacher.

"Nicole wanted to be 18 at age 12," Yvonne says. "She was climbing out of her bedroom window at night and chasing off down the street. Each time she ran off, I would contact the police, of course. After about the fourth or fifth time they just said, 'No, we're not going to waste our time'. So then the Department for Community Welfare [DCW] got involved and their words to me were, 'She is adamant that she does not want to go home, so we have to look for alternatives for her'."

Nicole was placed in what the department called a temporary foster care situation. On November 9, 1985, Yvonne wrote to her local MP, pleading for the return of her daughter. It was the first of hundreds of formal letters Yvonne would spend the next 27 years addressing to politicians. "My child has run away because she has been unable to get her own way at home with regards to such things as going out at night, wandering the streets, and keeping company with people of dubious character," she wrote. "And she knew that the DCW would assist her.

"The following is a conversation I had with my daughter the day before she ran away: Nicole - 'Mum, I want to be made a ward of the state.' Me - 'Do you have any idea what that would mean?' Nicole - 'Yes. [Nicole's friend] is a ward of the state and she is allowed to do whatever she likes.'"

By 13, Nicole was bouncing between temporary foster care and kinship care with Yvonne's relatives. When Yvonne landed a teaching position in Queensland, Nicole refused to move with her. For Yvonne, the job presented a way out of her small town as well as offering permanent employment with suitable holidays. "She just refused to come with me," Yvonne says. "So the Department said they would have to make her a state ward."

For the next two years, while Yvonne pleaded with authorities to return Nicole to her care, Nicole drifted through at least four foster care placements, running away from some, dragged away from others. At 15, the DCW placed her in a foster family. It was here that Nicole fell pregnant. By 17, she was mother to two children and living in a violent relationship.

Even when Nicole and her children moved to Queensland, closer to Yvonne, things didn't improve. She took up with more violent men. She had four more children, the last three to a particularly violent man who also introduced her to drugs. "I went around to Nicole's house one day," Yvonne continues, "and she was cowering in the corner holding this little baby and this monstrous man had a television set in his hands, holding it above his head ready to throw at her and the baby." Yvonne discovered that Nicole's youngest child, still a baby, was being fed and cared for by an older sister, aged 10. "She'd been getting up and giving her the feeds and not going to school," Yvonne says. "I rang the Department of Child Safety and I said, 'My daughter has a baby and she's taking drugs and I need someone to help her with the children until she's up on her feet'." She regrets ever making that call. What followed, Yvonne says, was "10 years of absolute horror".

At 27, Nicole had given birth to six children (one child was killed in a road accident while staying with his birth father). In the decade following Yvonne's phone call for help, Nicole's remaining five children were split up, bouncing between kinship care and foster care placements. Yvonne never stopped agitating the department, pleading to keep the children together. She formally applied for custody of her two youngest granddaughters, aged four and five, whom she saw as the most vulnerable. Ignored by the girls' case worker, she went public in the local newspaper in 2004: "Two innocent little girls are being denied the right to be cared for within their own family, where they would be the sole beneficiaries of our love and attention," she said.

Over the next five years the two youngest girls became lost in the system, like their mother before them, running away, dragged from placement to placement.

On October 1, 2010, Yvonne was granted care of one granddaughter. Two months later she received another phone call explaining how, due to a dearth of foster placements, another granddaughter had been living in a motel room, under the care of shift-changing youth workers. The case worker granted Yvonne temporary care of the child over the Christmas period. Yvonne wrote a letter to the department expressing her deep concern over the emotional and mental effect the multi-placement out-of-home-care system was having on her grandchildren. "[She] is a most disturbed child," she wrote. "The night before she was due to leave here, [she] called me into their room. She had gagged [her younger sister] and bound her feet and legs together with duct tape and she was standing over her with a carving knife, pointing it at her throat ...

"In my opinion, the best thing Child Safety Services can do for these girls is to return them to their biological mother, which is where they all want to be. Obviously she will not be able to manage them without support, so might I suggest that the money and resources spent on keeping [my granddaughter] in a motel with a youth worker would be better spent on reuniting the family and providing the support they will all need to be able to move forward."

Meanwhile, Nicole got herself clean from drugs. She met a good man, a shopping centre janitor who greatly assisted her physical and mental recovery. She was allowed one-hour supervised visits once a week. Yvonne communicated constantly with the department, pleading for extensions of the contact time, campaigning tirelessly for reunification for Nicole and her children, but it never came.

In September last year, Yvonne told her family's story to Commissioner Carmody. On October 29, she received a letter from child safety minister Tracy Davis, saying: "I understand that the case plan goal for the next 18 months is reunification of the children to their mother." Reading those words was the first ray of light in a tunnel Yvonne had walked for 27 years. "I learned a long time ago to never be elated by anything concerning Child Safety," Yvonne says. "But I was hopeful in that moment."

The next day, Nicole's partner returned home from work to find Nicole lying in the entrance to her bathroom. The girl with the toothy smile and the blue-ribbon pigtails was dead, aged 39.

In the Brisbane Magistrate's Court, former Family Court judge Tim Carmody unravels the volatile mess of Queensland's child protection system. This is a system where child intakes have risen 60.5 per cent between 2006 and 2011. It's a system where children in care are 3.7 times more likely to suicide; where indigenous children are five times more likely to be assessed; where the baton of trauma is passed through family generations. It's a system that indigenous mothers in Far North Queensland - where last year 275 indigenous children were placed into out-of-home-care compared to 93 non-indigenous describe as "a stolen generation just with another name". It feeds and is fed by a statewide domestic violence epidemic that saw 6763 women access domestic violence support between April and June 2012. It's a maze with a hundred entrances and very few exits, where addiction meets isolation meets bureaucracy meets a child raped by his neighbour as a boy and arrested for child abduction seven years later.

After two months swimming the murky waters of child protection in Queensland one emerges for air disoriented, head spinning with stories: children being taken into care after bringing pornographic footage of siblings to the attention of police; state wards eating broken glass to vent their frustrations; an educator reporting child safety officers who took three months to remove a child who had been raping his sister; the Department of Child Safety being notified of a mother with post-natal depression abusing her baby, only to discover the baby is the child of the mother's grandfather.

And then there's a father, John, whose son died at the age of two in 2009 while in the care of a 74-year-old foster carer. A coronial inquest in July last year heard that the carer, who had up to five children and was reluctant to take another, was suffering an illness and was possibly unconscious when it was alleged the boy rolled from a bed and hit his head. He spent six days in a coma with a fractured skull before he died.

Despite protestations to child safety services by John - a recovering drug addict who believed the carer was not equipped to look after his son - the boy had been placed with the elderly woman by foster agency Families Plus, working on behalf of the state government. During the inquest, a child safety manager admitted she did not return John's phone calls, rendering him, said solicitor Sandra Sinclair, "impotent by a system that didn't want to hear his concerns".

Coroner Kevin Priestly is still preparing his findings on the matter as John wages a war against the child protection system. He's raised an internet army of parents (with a website that has received 34,000 unique visitors in the past six months) angered by the removal of their children by Child Safety departments. John names and shames, having crossed the lines of defamation months ago. He will go to prison to wage his war. "My life is over since the moment I lost my boy," he says. "I just want to hurry up and die."

In a quiet cul-de-sac, three hours' drive north of Brisbane, Barbara Harris, 73, readies three of her children for an amateur theatre production they're starring in this afternoon. A boy, 14, marches through the back door of Barbara and Bill Harris's rambling home adorned with framed photos of the 200-plus children they've raised in 50 years of foster parenting.

No matter how hard they tried all those years ago, Barbara and Bill, 79, weren't blessed with the gift of their own birth child. Instead, they gifted 200 kids with a love so deep and accommodating that the memory of a child who briefly passed through their doors decades ago can still bring tears of joy.

The boy opens the fridge, digs into a bag of biscuits. "Mum," he says. "Can I eat one of these?" "No!" Barbara shrieks. "They're for the dog." The boy laughs, closes the fridge. Barbara rolls her eyes. There's a wooden sign above her kitchen window: "Don't worry about the dogs, beware the kids."

To spend a day in the company of Barbara and Bill Harris is to enjoy a masterclass in the parenting of teenagers. They currently care for five foster kids, who call them "Mum" and "Dad" - not because they were asked to but because they wanted to. "The best way of introducing kids to a home is to not do anything at all," says Bill, a former cattle station manager. "You just leave them. You don't push'em. Just let'em fit. You don't go at them with all this talk. They need love. They need food. That's it."

This will be the couple's last bunch of kids. Once their two youngest - one of whom they've loved since he was nine days old - make it through university or get themselves a job, Barbara and Bill will, at last, accept an empty nest. It's been 50 rich and meaningful years, though few of them were easy. Kids seem more damaged these days, Barbara says. Their scars are deeper, their traumas more labyrinthine.

Foster care has a maze of problems of its own. Carers speak of entering the sector with best intentions and then having nervous breakdowns one year in. Others speak of developing a deep love for a child and then having that child taken away to another placement. They speak of intrusive departmental officers so officious and risk-averse that any trace of positive emotional connection is quickly sapped from carers too scared to embrace a crying child.

"We have three different offices all looking at us once a month," Bill says. "And they come around and ask us how we're looking after our kids. How degrading You're here for 50 years and they're asking us all these questions you'd ask a first-time carer. It's called protecting your own butt," Bill says. "That's what it's become, from the minister down."

"I don't believe we're partners with the department," Barbara says. "They'd have a far better chance of retaining foster carers if they did treat us as equals," adds Bill. "The department people are young and most of them are inexperienced and they like to come in here and tell us what we've got to do. And we say, 'Hey, we know what we got to do, and you're not here all the time, we are'. They should treat foster carers as a very integral part of the team. Without foster carers, they [the kids] would all be in bloody institutions." (Indeed, with the national taxpayer cost of out-of-home-care placements reaching $1.8 billion last financial year, there is valid fear in the foster care sector of the government returning to the institutions of old.)

As it is, governments already outsource the care of children in what has become a burgeoning industry. The Department of Communities, Child Safety and Disability Services has sent The Weekend Australian Magazine a list of 41 non-government transitional care organisations operating in Queensland alone, receiving funds from the government to facilitate out-of-home-care placements. Trauma has become big business in Queensland.

Life Without Barriers is one of Australia's biggest non-government care providers; in 2011 it received $238 million in state and federal government grants. In December 2010 the NSW Ombudsman announced it was investigating Life Without Barriers' probity checks on carers following media reports of a child placed with a carer with a history of sexual assault on young people, and of another foster child living with a man whose own four children had been removed. The investigation led to the organisation releasing a 2011 review of its services, admitting "12 children were placed at significant risk due to very poor practice with respect to carer assessment, carer approval processes, and placement matching". It committed to reforms delivering "additional frontline staff, better supervision and more sophisticated quality assurance processes".

Scott Bray, Queensland's Life Without Barriers director of operations, says LWB provides family-based care to 308 young Queenslanders. It receives $27 million from the state government for funding of its foster care services. Bray is quick to stress the "stringent accreditation processes" and training schemes such organisations must undertake.

Bob Lonne, a professor of social work at the Queensland University of Technology and a former state child safety officer with 30 years' experience in child protection, says that between 1997 and 2011 he counted 32 state and federal inquiries into child protection, all of which have served to create a system he describes as too "proceduralised, managerially organised, risk-averse and punitive in its approach".

"We know that staff are stuck in front of a computer rather than actually working with people," he says. "Then you might be yelled at and abused by angry parents and that will be the straw that breaks the camel's back and who would blame them. The upshot of that is a constant need to retrain people, and a lot of people with inexperience. From children's points of view it can sometimes feel like a revolving door." A report-based, risk-averse approach, Lonne says, has created a system where parents self-incriminate if they speak the truth.

In Far North Queensland, says Marja Elizabeth, CEO of the Queensland Indigenous Family Violence Legal Service, indigenous mothers are so frightened of having children removed from their care - with little hope of reunification - that they are not reporting incidents of shocking domestic violence. "We've got women who want the violence to stop, but they're too terrified to say there's violence because the impact of losing their children is far greater," she says.

"People in the communities are calling it a stolen generation just with another name. How many people in your world do you know have got children who are under Child Safety care? If you're in one of these Aboriginal communities that we service it would be impossible for you to not have someone in your family that's either under Child Safety, or has been under Child Safety, or is terrified of being under Child Safety. It's like a war zone, in terms of Child Safety. It's a bunker-down mentality."

Rob Ryan, a former Child Safety officer, recently became Queensland director of Key Assets, a fostering agency specialising in out-of-home care for children with complex needs. "Nineteen years I've been in child protection," he says. "I've got a bachelor of social work, postgraduate training in family therapy, a master of professional education and training and I've also got postgraduate training in industrial relations and human resources, and after 19 years I'm just about ready to be a very good entry level worker. That's the crux of it. It's not a simple job, no matter what part of the system you're working with."

Everything's grey in child protection. Whenever anyone speaks in black and white, Ryan tells a story of a boy he helped remove in the late '90s. He was 12 and presenting at school with bruises on his legs. Ryan learnt the boy's stepmother crushed his left-hand fingers with a hammer because she didn't believe he should be writing with his left hand. Other nights, she would cut him while he bathed. At night, he'd climb over his neighbour's fence to find solace. The next-door neighbour began sodomising him. After removing the boy, Ryan sought out the boy's natural mother, who said she wanted nothing to do with the boy. So he was placed into state care. Seven years later, Ryan saw this young man featured in a crime story in Brisbane's Courier-Mail. He had been arrested trying to abduct a young child. Every action has a reaction.

Kristian Wale is CEO of the Shaftesbury Centre in Brisbane, which often educates worst-of-the-worst cases of children in out-of-home care. "We've had young people being used as prostitutes by their parents," he says. "How do you sit down with them and say, 'Learn'?" The answer, he says, is trust. "Once they trust you they will change. But trust takes time. Trust takes stability."

Marja Elizabeth recognises the "lose-lose situation" that Child Safety officers work in: "If they remove children they are the worst people in the world. If they don't remove children and then something occurs - and it has before - then Child Safety is on the front page of the newspaper."

The goal, says Elizabeth, should be all sides working towards a plan that involves safe family reunification when appropriate. But reunification is not something that appears to be a key part of the department's child protection model. Asked how many children placed into care in Queensland in the past 10 years have been successfully reunited with their families, the department replied: "Data on reunification is not currently available but the department is preparing to start capturing the information in the near future."

Insiders on all sides say the way through is an emphasis on early family intervention, removing the problem before the child, allowing a safety officer to do what they're trained to do, a multi-strand system equipping parents to be parents. "Early intervention," says 50-year foster mum Barbara Harris. "All children are better off in their own families, if they can be." Says Bill Harris: "Instead of ripping in and ripping the kids out, we could help them by asking, 'What's wrong with the house and how can we fix it'?"

In November, NSW family and community services minister Pru Goward released a discussion paper proposing sweeping reforms to the way we look at at-risk homes. She says: "Many children and young people in care experience the detrimental effects of too many placements ... The discussion paper proposes that we first try to help families change so their children can live at home. If this is not possible, children should then live with other family members who have long-term guardianship, and if that is not an option then open adoption. Children should only go into [foster care] as a last resort."

They are reforms drawn straight from what the child wants: stability.

In Wacol, in Brisbane's west, among sleepy streets lined by lazy kangaroos, is the Brisbane Youth Detention Centre. There is stability here. Out of the 110 detainees, 25 per cent are on Child Safety orders. About 55 per cent of detainees are Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander. Centre director Glen Knights walks into a detainee common area running off a wing of small concrete cells, locking the door behind us. "They found that 70 per cent of the boys coming in here have some diagnosable mental health issues," Knights says. "Ninety per cent of the girls have a diagnosable mental health issue. In the community, a lot of these young people go unassessed, untreated, unhelped."

Here, it is not uncommon for a detainee to experience the first dental check-up of their life. Many have never had immunisations. One boy had never worn shoes. Last weekend, the centre opened it gates for an 11-year-old boy addicted to glue-sniffing. Other kids here will go a whole year inside without a single visitor.

Tony Ward is the centre's deputy director. He started his career in child protection in 1989. "The last job I had in Child Safety was two and a half years ago and I was manager in Toowoomba," he says. "I saw two decades' worth of change. What Child Safety was doing at the end was far more complicated than it really needed to be. It was burdened. It became risk-averse and encumbered with too much paperwork. Whereas back in the'80s, '90s, you had a case load. I knew my families, I knew my kids, they knew me. It was much more traditional help that you gave people. Of course you removed kids, but what became of that approach was that it became so prescribed, you had tools and forms and you couldn't make a decision until you'd done A, B and C. And the problem is, and the risk that Child Safety now faces, is that they don't put as much weight or credence on somebody's professional judgment."

Lately, the darndest thing has been happening to Tony Ward. He keeps seeing young men he removed from homes as children walk through the gates of the Brisbane Youth Detention Centre. "There are three of them, one's 13 and two of them are 16, and I remember trying to work with their families when they were being born. It's very sobering. You can see the life trajectories that these guys have had."

And Yvonne saw it playing out in her family. Around Easter 2011, Nicole's eldest son, Ryan, aged 18 and out of state care, fathered a child of his own. Two Child Safety officers soon arrived on his doorstep with two police officers. "They said, 'We believe this child is at risk and we're taking him'," Yvonne says. "We were never told really what the notification was about. Why he was considered to be at risk. It was just so obvious that we were a family known to them and that it was, 'Oh, quick, let's go in and get the next one'. They went backwards and forwards to court. [Ryan] had to go to court a couple of times and do their parenting courses and then they decided that his son was safe around him."

The reason Yvonne has been looking through her box of photographs is because she's making a DVD of her daughter's life that she will present to her grandchildren. She wants to show them their mother's life, every side of it, for better or worse, including the sides they never saw. The musician. The champion school basketball player. The woman who loved interior design. She's been dwelling on a photo of Nicole as a newborn in hospital, wrapped in a bib that bears the family name. "You start off with all these good intentions for your child," she says. "All these hopes." She takes a moment to cry.

A coroner is yet to determine how Nicole died. Today, three of Nicole's children remain in out-of-home care. One, Yvonne says, is living in a residential care facility and hasn't been to school in two years.

On the morning of November 8, Yvonne delivered her daughter's eulogy. She spoke of a woman vulnerable to bad influences, a teenage rebel who made for trying times, but a woman who loved her kids. She looked out across the chapel and saw all of her grandchildren sitting along a wooden pew. And she thought how much Nicole would have liked to see them sitting like that, all together. Reunified.