Jurassic ark: the secret mission to save the Wollemi pines from bushfires

They have survived the dinosaurs, meteorite strikes and ice ages, but as summer fire threatened to annihilate them, a daring rescue mission began.

Like everyone associated with the Wollemi pines, Berin Mackenzie – a conservation scientist with the NSW Government – had been obsessively following the Gospers Mountain fire as it galloped through the vast and rugged national parks to the north-west of Sydney in the lead-up to Christmas. “I’d been monitoring the fires since they started, watching it impact other sites of significant value, but no one ever imagined it would travel as far as it did… it was clearing some really large gorges that would normally pull up a fire. It was just leaping right over the top of them. Once you get extreme fire weather like that, all bets are off.” There was nothing normal about these fires. Nothing was safe. The fires were destroying forests that had been cleared of ground fuel in controlled burns two years before.

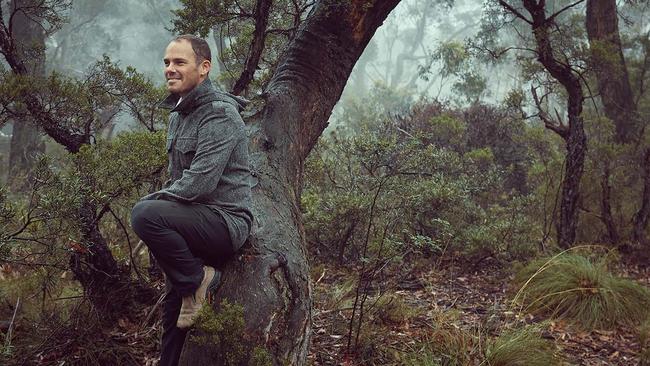

Mackenzie was raised in the Blue Mountains town of Leura and knew the surrounding parks as only someone who had been schooled in their ways since childhood could. “When we were growing up the national park was our babysitter,” he says. “It was a single-parent family so when Mum was at work we would be off in the park, playing in the waterfalls, climbing the sandstone cliffs and exploring the rainforests. The rule was we had to be home no later than an hour after dark.”

He became fluent in the language of the untamed scrub, bushwalking through its valleys and abseiling into its canyons. The mountains inspired him to pursue a science degree at Sydney University and go on to do honours in plant ecology. And then, in 1996 – at the age of 23 and nearing the end of university – his mum, Gail, took him to see the documentary Wild Australia: The Edge, by filmmaker John Weiley. “It told the incredible story of the Wollemi pine’s discovery and featured footage of scientists conducting ecological research on it,” he says. “It was so exciting and inspiring to watch them, and I remember telling Mum how much I’d love to be one of those guys some day.”

Mackenzie pursued a career with the NSW environment department and in 2013 his dream came true when he was invited to join the Wollemi Pine Recovery Team, a unit charged with ensuring the ancient species’ long-term survival. And then, before Christmas, when things turned bleak, he was drafted into a small team with the mission of saving the pines from obliteration.

The Wollemi pine has lived on Earth for about 200 million years. It has seen off the dinosaurs and survived meteorite strikes and ice ages. It was once the dominant species across the mega continent Gondwana. As the land masses split, and Australia became drier, it retreated to this one tiny toehold, a deep canyon of Wollemi National Park a couple of hundred kilometres from the CBD of Sydney – fewer than 100 mature trees in four small groves. Fossil records reveal the Wollemi pine disappeared millions of years ago everywhere on the planet except here. And now the great survivor was seemingly one ferocious firestorm away from annihilation.

‘We’ve got to throw everything at this, but it has to be a covert operation’

It had to be saved. But, as NSW environment minister Matt Kean explains, the politics were tricky. Many parts of the east coast of Australia were ablaze, with people and property at risk; imagine if a Sydney shock jock got word these greenies were diverting resources to save a tree! “I got an alert from Parks to say, ‘Look, we’ve got a serious issue in the park with the pines’,” Kean tells me. “I thought, ‘Well, shit, this is a living fossil! I’m not going to be the first environment minister in the history of this nation to allow Australia’s living fossil to be bloody incinerated. We’ve got to throw everything at this, but it has to be a covert operation.”

And so, an urgent and secret plan was hatched to save the wild Wollemi pines. They’d scrounge planes and helicopters when houses and lives were not at risk. It would take a great team effort – and some heroic individual deeds – to succeed.

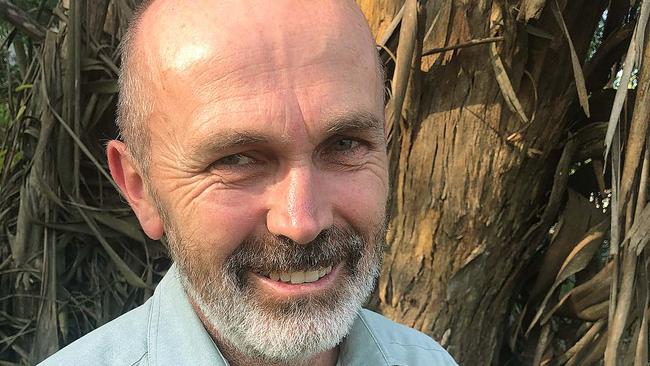

The discovery of the Wollemi pine has been likened to finding a small herd of dinosaurs roaming free in a remote forest. But the bloke who found them, Dave Noble, admits he could have easily strolled straight past these dino-pines when he stumbled into the grove with some mates on a spring day in 1994. “We stopped for lunch, pulled out our sandwiches and we sat down right beneath this big rainforest tree… I was drawn to the trunk, which looked like someone had sprayed chocolate crackle all over it. I thought, ‘That’s a bit unusual.’ But if we hadn’t stopped for lunch we might have walked straight past and its discovery might have been left for another time.”

Back in the early ’90s, Noble was building walking trails for the National Parks and Wildlife Service. He’s now a ranger and I meet up with him at the Blackheath parks office. He’s a big, gentle man who still spends most weekends out in the bush canyoning, kayaking and walking. He took a shine to a moppish hairdo sometime in the ’70s and has remained faithful ever since.

Noble has always been an adventurer, drawn to the unknown, and in the early 1990s the great unknown was Wollemi National Park, a wilderness comprising half a million hectares of rugged forest and dramatic sandstone cliffs. It’s part of an unbroken series of national parks that straddle the Great Dividing Range, stretching for almost 300km, inland from Wollongong in the south to Newcastle in the north. This seemingly impenetrable barrier kept the first European settlers hemmed in on the coast for their first quarter of a century on the continent.

“During the 1970s and ’80s a bunch of famous canyons were discovered in the Blue Mountains [National Park],” Noble tells me as news of current fires cackles on a two-way radio in the background. “But very little of Wollemi had been explored.” In the early ’90s, Noble and his mates would drive up there and chart virgin territory, marking new routes on topographical maps. Many of the canyons they discovered could only be accessed by abseiling sheer 30m-high cliffs and so would probably have been inaccessible even to Aboriginal people. “It was pretty exhilarating to abseil into a remote canyon and be almost certain that no human had ever been there before you.”

On that spring day in 1994, Noble and his matesset off early, driving up to Wollemi to explore new canyons they’d identified from aerial photos. “We did a few abseils, scrambled down a few rocks and had a couple of swims, and ended up in a side canyon where we stopped for lunch,” he says. As they slung off their packs, he noticed that unusual “chocolate crackle” texture of the trees’ bark. He knew most of the rainforest trees, the sassafras and the coachwoods, but not this one, so he collected a piece of foliage to inspect later. “We then set off to explore another canyon without thinking too much about it.”

Back in Blackheath, he took the sample to his parents, keen bushwalkers who knew their plants. “Dad had a look at it and between the two of us we couldn’t work it out,” he recalls. A few days later, he plonked it on the desk of Wyn Jones, a NPWS naturalist. “Wyn, whaddya reckon this is?” Jones had a quick glance. “Leave it with me and I’ll get back to you.” A few days later Jones asked if the foliage came from a small bush or a fern. “No, it comes from a 40m-high tree growing out in the middle of Wollemi,” Noble told him.

Jones was intrigued, so a week or two later Noble took him to see the trees. “I’ve never seen him so excited,” says Noble. “Not before and not since.” Jones, normally a staid, unflappable character, was scooting about the forest like a dog on lino, collecting leaves, branches, cones, whatever he could get his hands on.

Jones took the samples to Jan Allen, a botanist at the Blue Mountains Botanic Garden, and they set about trying to identify the tree. They wondered if it may have been an exotic species, introduced by a seed dropped by a black cockatoo. “They basically had to do a search of every living tree in the world,” says Noble. It matched nothing, nothing that was living, and it would turn out to be one of the greatest botanical discoveries of the 20th century.

“Once I realised we had stumbled across this new genus, a whole new species, I realised what a great privilege it was, in this day and age, to do that,” Noble tells me. His curiosity and decision to put that sample in his pack has been immortalised. When it came to naming this new species, the name Wollemia nobilis was chosen – Wollemia after the park and nobilis as a nod to Dave Noble.

Having been completely unknown to science 26years ago, apart from vague and dusty fossil records, Wollemia nobilis has become one of the world’s most examined trees. Last year, scientists from Deakin University and the Royal Botanic Garden Sydney began an ambitious project to map its entire gene sequence, a project that associate professor Larry Croft likens to mapping the genome of Tyrannosaurus. “This can only be done because the Wollemi has survived largely unchanged for more than 100 million years, whereas all the dinosaurs, except for the birds, have been extinct for more than 60 million years,” Croft says.

Soon after its discovery a commercial nursery was granted the rights to propagate and commercialise the tree – partly to reduce the temptation for collectors to steal seeds and seedlings from the wild – and tens of thousands are now growing in botanic and private gardens around the world. The Royal Botanic Garden Sydney recently launched a citizen science project called “I Spy a Wollemi Pine”, to understand where around the world they’ve been planted and where they are thriving. Conservation biologist Dr Cathy Offord says that as an insurance policy, cuttings were also taken from every one of the mature wild trees and propagated; these young trees, each one a clone of its parent, are held in the Australian PlantBank. “They form what we call an ex situ population – effectively an insurance against loss in the wild.” It’s like having a cloned replica of every remaining wild rhinoceros.

The future of the Wollemi pine as a species seems assured, then. But to lose them in the wild would be a grave and damning reflection on us as custodians, says Dave Noble. “You’ve got to have that wild link,” he says. “It would be like having koalas and tigers only in zoos. It’s just not the same. It would be a great tragedy.”

And then, one day around Christmas, Noble had to contemplate that very prospect. Ordinarily he’d have been out on the frontline fighting fires as a volunteer, but he was recovering from an operation on his shoulder and was working in the fire control room. “Every day we’d get an infrared line scan showing where the fire was,” he says. One day he saw the fire getting closer to the pines and he left work that night wondering if they would survive.

Noble’s boss, the director of parks for the Greater Blue Mountains, David Crust, had been nervously watching the Gospers Mountain fire advance for weeks. But then the whole of his patch was alight. He was at the apex of a catastrophe. “We had five serious fires burning across the mountains,” Crust explains. “It was just insane.” Every single one of his 160 parks employees, including the clerical staff, was either out fighting fires or supporting those in the field. More than one million hectares would be burnt in this one region, four times the area of the worst previous fires. “There were fires everywhere, everyone was fully committed, and then in the midst of all this it became apparent that the Wollemi pines were under threat.” They had to dust off their rough plans to save them.

The plan, says the straight-talking Crust, “was not all that complicated – basically we were going to set up some pumps, some pipes and some sprinklers.” The idea was to moisten the ground around the trees. They would also try to slow the advancing fire by dropping lines of fire retardant in its path and helicopters would bucket the area with water. It sounded simple but the implementation was devilishly difficult.

As Murphy’s Law would have it, the two employees who’d written the plan and were best placed to implement it had left weeks before on long-planned holidays and were unreachable – one was hiking in the Himalayas, the other was in the Tasmanian wilderness. There was also the matter of water: the creek nearby had virtually stopped running so they’d be relying on a couple of small waterholes in the creek bed. Then they had to find staff, resources and helicopters. They had to prioritise which trees to save.

There is one main grove – the one discovered by Noble – where the pines have thrived and reached a height of 40m. The oldest tree has survived for about 1000 years. Within a 2km radius are three other groves with much smaller mature trees. A decision was taken to concentrate on the main grove. Staff and equipment would have to be helicoptered in to an extremely dangerous fire zone in the middle of a massive forest where, if the wind picked up and the smoke closed in, they might be trapped. And before they even got started, every piece of equipment had to be sterilised on site, as the pines are highly susceptible to introduced diseases.

Everyone jumped at the chance to be on the mission. One of the chosen four was Heidi Zimmer, who was doing her PhD on the pines. She’d recently had a baby, so she handed the infant over to her partner. The others were Phil Lamrock, a parks contractor; arborist Ian Allan; and Berin Mackenzie. “We got the call from Dave Crust in the morning and by that afternoon we were madly scrambling to buy equipment,” says Mackenzie, who was sourcing ropes and climbing gear; another of the crew was in Mudgee, buying pumps and hundreds of metres of piping and sprinklers. That night they got a crash course in how to operate the pumps and attach the sprinklers.

The fire was closing in on the pines, but the following morning they were unable to get enough helicopter support to take all their equipment in. However, they did manage to land a crew to make an on-ground assessment. Mackenzie says the situation was bleak – there was little water in the waterholes and the ground was bone dry. The pines carry scarring on their trunks that indicates they’ve survived fires decades before, but the fear was they might not survive one as intense as this.

Back in the helicopter, Mackenzie called his managers. “It’s pretty dire,” he said. “It’s not what we were hoping for.” Meanwhile, a VLAT (very large air tanker) was laying lines of fire retardant in the path of the advancing fire.

The team of four was helicoptered in next day. Tarpaulins were laid out and every piece of equipment sterilised as the fire advanced on the plateau above. They ran the pipes out to get maximum coverage of the grove, careful not to tread on any seedlings, then attached the sprinklers. There were two waterholes in the creek bed – they’d empty the hole closest to the pines and then pump water uphill from the other. “It was like a sprinkler system you’d see in a school ground,” says Mackenzie. They’d then have to wait for creek water to trickle down and fill the waterholes.

The next day they were winched down into the canyon again, and turned on the pumps. Everything was running smoothly – until the conditions changed. “There was a point early in the morning when the canyon started filling up with smoke and little bits of ash started raining down,” Mackenzie says. The situation was tense, but they had the utmost trust in their superiors to make the right choices about their safety. “We sort of looked at each other as the ash was raining down and just went… ‘Well, the radio is not going off’.” They worked for another hour before the decision was made to extract them.

Over the next week or so, whenever helicopters were available and the smoke wasn’t too dense, the team was dropped in to turn on the pumps, which would run until they were out of fuel. Mackenzie reckons it made a difference – he could feel the dampness in the soil and the leaf litter on the forest floor. You saved the pines, I say; you’re the hero. “Nah,” he says. “The hero in all this is Steve Cathcart. Steve saved the pines.”

‘They’re special and I feel a great responsibility to protect them…’

Access to the pine groves is severely restricted. The location is secret and Dave Crust is deliberately vague about exactly when the fire swept through. He doesn’t want amateur adventurers poring over maps and then trekking in and bringing disease. A few years ago a soil disease called phytophthora, root rot, was somehow introduced and it almost destroyed one of the groves. Anyone caught illegally accessing the site risks a $220,000 fine and two years in jail. “We’ve caught a few,” says Crust. “And we’ve prosecuted them.”

On a day close to Christmas, Crust and his staff were monitoring the fire’s progress. From their scanning equipment they could see it had swept through the chemical containment lines and was approaching the lip of the canyon containing the pines. “These pines are really important to me,” Crust says. “I worked as the park manager at Wollemi from 1997, a few years after they were discovered, and was responsible for their management… I’ve been out to the site maybe 30, 40 times and it’s otherworldly down there. They’re special and I feel a great responsibility to protect them… I don’t normally get emotional,” he says, becoming emotional, “but this is big, this is serious shit.”

The night the fire swept into the pine gorge, Crust was watching from the fire control centre. “That night it was bloody smoky so it was difficult to get a good line scan to see exactly where the fire was.” They had a rough idea, but no clue about how the fire was behaving. It was one thing for it to gently drop into the gorge but they were terrified it would come from another direction and race up the gorge. Helicopters had waterbombed the gully below to reduce this risk but still, the mood in the control room that night was “f..king intense”, Crust says.

He put one of his most experienced and trusted colleagues on standby to fly at first light over the pines and assess the damage. In the morning he was anxiously on the phone as they waited for the smoke to clear so the helicopter could take off. “Can you fly? Can you fly? Steve, can you fly?” The phone calls went on for almost four hours until around 10am, when the smoke had cleared and Steve could fly.

Steve is Steve Cathcart, the NPWS area manager at Tumut, who’d travelled up to help with the Blue Mountains fire. Cathcart was drafted into the team because he’d previously worked at Wollemi and had decades of experience as an “air-attack supervisor” fighting fires. “I was there so they could get the best bang for their buck with their planes and helicopters,” he says.

On this day, as the pine gorge was burning, they needed his expertise to direct the aerial bombardment. He was meant to remain in the helicopter and call in air support. But that’s not what happened.

The chopper took off and, in poor visibility, flew intoWollemi; soon it was hovering over the pine canyon. Below, Cathcart could see that the main fire front had moved through, but he could see fires still burning inside the pine grove. He knew that if it continued burning in there, trees would die. “Given the importance of each and every one of those trees, I knew what I had to do.” He was winched down into the gorge, alone. He had his survival pack, but – not expecting to go down – no firefighting equipment, not even a rake-hoe. But he did have a drum of fuel to power up the pumps.

He knew he was bending departmental rules going down alone, but he assessed the situation as safe – the last thing he wanted to do was place any of his colleagues in danger if they had to rescue him. “It was my decision to go down,” he says. “National Parks is not a job. You know, it’s a lifestyle to an extent… you’re forever doing over and above.”

Cathcart was hoping the irrigation lines would be intact and he could simply turn on the pumps, but some of the piping had melted. A large eucalypt had fallen from the cliff above and the head of it was alight, burning in the middle of the grove. His first task was to move the burning branches away from the pines, which he did by hand. He then went around the bases of all the mature pine trees, kicking the hot coals away from the trunks. He worked urgently but meticulously, knowing he had little time. The greatest danger was that another eucalypt would fall from the cliff above. But he wasn’t frightened. “To be truthful,” he says, “you don’t think of much, you just go into firefighting mode… ‘This is what is happening, this is what I need to do, these are the risks’.” The bush was silent: no cackling birds, no crickets and no burping frogs.

The pumps, miraculously, were undamaged. “They [the team who laid them] had done a fantastic job, thinking of exactly where they should leave them,” he says. Luckily, he’d taken a Leatherman multi-tool down with him and with it he began cutting and joining all the undamaged pieces of poly-pipe, jamming in rocks to plug leaks in the pipes. He filled the pumps with fuel – and, wondrously, they worked. “I was able to use the poly-pipe as a sort of fire hose to damp down the areas at the base of the trees,” he says. “It was a bit agricultural, but it worked.”

After two hours, as the winds began howling and the smoke came billowing in, he radioed a helicopter, which returned to extract him. His final task was to provide pinpoint grid references for a waterbombing helicopter. He was winched into his helicopter and, on the flight back to safety, saw a chopper fly past with a giant bucket dangling beneath. It, too, would only get one shot – the smoke was closing in and for the rest of the day it was deemed too dangerous to fly to the site. On the way back to base, Cathcart phoned his bosses on the ground. “I think we might’ve saved them,” he said.

Cathcart is dismissive of the hero label and says he was just a cog in an extraordinary team that saved the pines. “I just happened to be there at that time,” he says. “I knew that we probably wouldn’t get another opportunity to organise a team [to go down] and that the smoke would probably close in. It had to be me.”

‘Out of an immense catastrophe emerged this little green shoot of hope’

Matt Kean, the NSW environment minister, sayshe became emotional when he was told the pines had been saved. “The first thing I did was call Gladys,” he says of his call to NSW Premier Berejiklian. She was ecstatic. Saving those pines meant so much to so many people, Kean says. “The fires had been so devastating and out of what had been an immense catastrophe emerged this little green shoot of hope – that we had saved this remarkable piece of history.”

Some people, even some of his colleagues, had tried to use National Parks as a “scapegoat” for the fires, claiming a lack of hazard reduction had contributed to the crisis, Kean says. “National Parks has met all its targets and has doubled the hazard reduction it had done in the previous decade,” he insists. The Rural Fire Service deserves immense praise, he says, “but let’s not forget the amazing effort of the NPWS men and women who have been out there not only fighting fires in parks but protecting people and property. They are the crack squad when it comes to firefighting. They have been winched into dangerous areas to contain fires and have stopped them getting even bigger.”

When I tell the minister what Steve Cathcart did on that day, he sits open-mouthed in astonishment. He hadn’t known all the nitty-gritty details. “Get that guy’s name,” he says to his press secretary. “And the others too. I want to give them a service medal.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout