Jane McGrath’s terrible diagnosis drove her determination to die on her own terms

South Australia’s restrictive voluntary assisted dying laws would have been of no use to Jane McGrath whose personal battle highlights the plight of those lost in the margins of legislation.

Barbara McGrath couldn’t take her eyes off the green light on the hospital monitor that told her that her daughter Jane was still alive. As precious as that life seemed to be in that moment, Barbara was still coming to terms with the fact that her daughter was desperate to die.

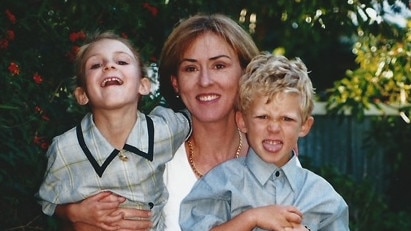

In March 2019, Jane McGrath, a humanitarian and immigration lawyer from Adelaide, had been diagnosed with a rare terminal brain disease, progressive supranuclear palsy. Each year just one or two people in every 100,000 are diagnosed with the disease. Their average life expectancy? A mere seven years. It would not be long before Jane, then 56, would suffer serious difficulties with the most basic of functions. Within a few years she would suffer serious problems with walking, balance, speech, and eventually swallowing. Jane was clear from the outset that she did not want to die this way.

“If you looked at the diseases you’d prefer not to have, this one would be high on your list,” says Dr Jane Hecker, one of Jane’s doctors. “The guaranteed course for Jane was progressive neurological degeneration [culminating in] a bedbound state, which is what nobody wants to happen.”

Jane had always dealt with life’s curveballs with apparent ease. She would look for the positives and respond with action, throwing herself into exercise and work, surrounding herself with friends and family, and planning trips away. But this was different. Says her 30-year-old daughter Lucy: “I think the diagnosis was the first time in my life I had seen mum pessimistic. All her coping mechanisms didn’t work because there were no positives. There was no hope. It was only going to get worse.”

As a partner at law firm McDonald Steed McGrath, Jane managed a busy immigration practice. Among her clients were asylum seekers, and orphaned refugees from war-torn countries seeking to be reunited with relatives in Australia; she worked pro bono for many of them. “She fought hard and she never gave up, even when decision-makers told her no,” says colleague Natalie May. “She was creative when there was a blockage.”

As her business partner Abigail Steed recalls, Jane didn’t use the word “no” herself too often. “If she was asked to take on six new clients, even if it meant having no sleep for the next three weeks, she would say yes almost before the question was out.”

“She pretty much said yes to anything,” agrees Jane’s best friend, Helen Rice. They had met through a mothers’ group several decades ago. Once their children were of school age, drinks at Jane’s became a regular Friday night ritual for friends to come together for a chat and a dance. “Mum would pick us up after school and anyone she bumped into would be invited back to our house for drinks,” says Lucy. “People gravitated towards her. Everything seemed lighter with Mum around.”

But her diagnosis was too heavy for Jane to bear. Her family told her they would care for her until the end – but she insisted she didn’t want to be cared for, to be unable to communicate or feed herself, to be wholly dependent on others at home or in a nursing home. She began to investigate options for assisted dying overseas. In South Australia. at that time there were no laws permitting assisted dying. Her family saw how determined she was and supported her decision to seek help to die the way she wanted.

“She was very fearful,” says Jane’s mother Barbara. “I gave her my blessing. I did not want her to suffer mentally more than anything.”

Jane and her husband, Chris, travelled overseas so Jane could talk to assisted dying services in several countries. She decided on Belgium where physician-assisted dying (“euthanasia”) was available for people in her situation. This involves a doctor administering the life-ending substance as opposed to the person taking it themselves. In Australia, the term “voluntary assisted dying“ (VAD) covers both practices, but the way in which the method is chosen varies from state to state. Jane was unable to access any assisted dying laws outside of South Australia as she wasn’t a resident.

Euthanasia was legalised in Belgium 20 years ago. The law there requires that a person is legally competent, able to make a well-considered, repeated and voluntary request, and is experiencing constant and unbearable suffering, either mental or physical, that cannot be alleviated, caused by a serious and incurable medical condition. A terminal diagnosis is not necessary for adults, and no time-frame regarding life expectancy is imposed. In June 2019 Jane signed up to a tentative plan with the Belgian assisted dying organisation LEIF to enact when she was ready.

As time went on, however, she grew more anxious and fearful. In August that year, she tried to take her own life by swallowing a bottle of pills. Her then 23-year-old son, Sam, found her unconscious; an ambulance rushed her to hospital. In the Intensive Care Unit at Flinders Medical Centre, Jane’s parents came in to see her and were shocked to see her intubated. While Jane’s daughter Lucy was talking to them, her grandmother Barbara said she was feeling “weird”. Lucy remembers thinking little of it; they all felt weird. The family knew Jane wanted to die but had no inclination of how desperate she felt. The shock of this realisation was about to have a snowball effect on the family. Lucy looked over at her grandmother and saw her slumped in her chair, unconscious. Barbara was having a cardiac arrest. The family looked on in horror as staff resuscitated her. After she had been revived, they were told that Barbara had “broken heart syndrome”, or takotsubo cardiomyopathy, where the heart muscle becomes suddenly weakened as a result of severe stress. The shock of Jane’s desperate act was too much for her mother’s heart.

In those first few days, the family was dealing with the dual crises of having both of them in the ICU. Barbara lay in a bed a few feet away from Jane, her eyes locked onto that green light that reassured her that for now, her daughter was alive. Still in shock, Barbara wasn’t ready to let her daughter go quite yet, not this way.

Jane and her mother both recovered, and life for the family returned to a semi-normal state.

–

Jane received both psychological and psychiatric support, but when family members asked her if it made her feel any better, she was adamant. It didn’t.

–

Although certain that she wanted to die on her own terms, Jane had in all other respects much to live for. Before her diagnosis, she’d found a sweet spot in her life. Following the end of her marriage in 2013, Jane believed she would never be in another relationship – but just six months later she had fallen in love. Jane and Chris’s relationship began with a twist. Mutual friends had arranged a dinner that would include them — Jane realised this was an attempt at matchmaking.

Chris Kourakis is the Chief Justice of South Australia’s Supreme Court. He and Jane knew each other through legal circles, though not well. Not wanting to feel awkward on the night of the planned dinner, Jane wrested control: she texted Chris and asked him whether he wanted to meet beforehand. He did. They met at a wine bar, and the conversation flowed. By the time the dinner came around later that week, Jane and Chris walked in hand-in-hand, leaving their hosts astounded.

Chris was later to say in a family video: “That little thing shows an enormous amount about Jane. It shows how much she understood people. It shows her directness and courage, and I was really taken aback by that.”

Although Chris declined to be interviewed for this article he was not opposed to its publication. “Chris and Jane were soulmates,” says Helen. “They had a lot of shared interests. They loved talking about the law and social issues and were both big believers in human rights. It was a real love match.”

Jane’s daughter Lucy agrees. “It was a mutual admiration. She kind of challenged him, brought some fun and energy into his life, and for her. Chris was a grounding influence. It was the happiest I’d ever seen her in those few years they shared before her diagnosis. It was very obvious to everyone how happy they were.

Lucy adds: “Chris wanted to make sure mum knew that he was very willing to care for her during the later stages of her illness. But once it became clear how distressed she was about the nature of her condition and how the end of her life would be if it progressed, he was understanding and supportive of her decision.”

Jane and Chris married in March 2017, and made plans to build a house, with Jane designing a large entertaining area to accommodate social gatherings. But a mere 18 months later, she received her devastating diagnosis. From that moment she no longer felt invested in future plans. She couldn’t see herself in that new house. A day after a meeting with the architect, Jane had made that first attempt to take her own life with pills. Says Lucy: “Trying to end it all herself quickly had seemed preferable to the idea of packing bags and catching planes as if going on holiday when the sole purpose for that holiday was to die.”

Finally, Jane told her family that March 2020 would be the right time for her to go through with assisted dying. With the advent of Covid, however, it proved to be exactly the wrong time. Borders shut and Jane’s escape hatch from her dreadful destiny was now unreachable. At the same time, her condition was deteriorating fast: she was losing her balance and having trouble speaking. She was no longer able to go to the gym and became withdrawn.

“She stopped wanting to see people other than those really close to her,” says Lucy. “I think she was embarrassed. She didn’t want people feeling sorry for her or seeing that she wasn’t herself. By then she had trouble speaking, and felt self-conscious.”

One night in February 2021, Jane made a second attempt to end her life, swallowing the remainder of the pills she had stashed since the previous time. Again, it was unsuccessful; Chris found her in their spare bedroom, still conscious. In the fallout from that incident, Jane stepped up attempts to get to Belgium, investigating exemptions. Soon there was talk of borders reopening and when they did, Jane set a new date of March 2022 only to bring it forward a month fearing that she might fall and break something, preventing her travel.

There had been some happy news with Lucy’s announcement in April 2021 that she was pregnant with her first child. Jane was thrilled. Something that had upset her most about her fate was the fear that she would be deprived of being a grandmother. Lucy’s daughter Hazel was born on December 21, 2021. Mother, daughter and granddaughter spent as much time as they could together. Jane wrote a letter to Hazel quoting a lyric from the song Hymn to Her by the Pretenders – “Something is lost but something is found” – that captured perfectly how she felt about Hazel’s birth.

In the weeks leading up to her departure for Belgium, friends and family came to say goodbye. Days before leaving, contact was limited to close friends and family in an effort, sadly ironically, to keep Jane safe from Covid. Another hurdle in a plan full of obstacles.

It was proposed that Chris, Jane’s son Sam, then 28, and two friends, including Helen Rice, would accompany her on her last journey. Lucy wanted to go to Belgium to be with her mother but Hazel was too young to be vaccinated, so she had to accept that she couldn’t be there.

For Jane, who had welcomed people into her life so readily, a last goodbye felt impossible. On the day she left, as Lucy prepared to drive her to the airport, family members were waving to her from the footpath. As Jane waved back, smiling, she said to her daughter: “Just drive Lucy, just drive.” At the airport, Lucy only had time for a coffee with Jane and a quick hug before the boarding call came and her mother disappeared down the ramp onto the plane.

Lucy had written her mother a letter. “I told her that she had taught me to live with integrity and show compassion for others, how to be courageous and tolerant, and that I was thankful to have her as a role model,” Lucy says.

There were more roadblocks on the way out of Australia. On arrival in Melbourne, preparing to depart the country, the group was told that due to Covid only family members would be allowed into Belgium. But Jane’s friends were accompanying her not only to support. They were also required by LEIF to be present as independent witnesses – without them, Jane couldn’t proceed with her plan. After some persuasion, they were allowed to leave but only if they signed a waiver that they couldn’t sue the airline if denied entry to Belgium. With all the worry about what lay ahead, the fear that Jane might not get across the line at the border only amplified their stress.

The plane trip was sombre but they tried their best to lighten the atmosphere with a glass of bubbles. They were relieved to be granted entry on arrival to Belgium. The group had dinner together the evening before Jane’s planned death. “Jane spoke incredibly well that night,” says Helen. “Her mind was sharp, which was good and bad; she knew exactly what was happening but she was physically struggling. She thanked us all for coming and doing this for her. She told us that she loved us all.”

At the hospital the next morning, Jane’sroom had none of the starkness of a regular medical facility. Helen was struck by a photograph that covered an entire wall. It was of a sandy beach with a boardwalk leading to the sea; it looked exactly like Jane’s favourite beach at Port Elliot back home. She hoped that it diverted Jane from the view outside her window overlooking Brussels’ winter-bare birch trees, reminding her how far she was from home. Two doctors came in to see Jane. An independent doctor first assessed her and asked her if she still wanted to proceed. She said that she did. The doctor who would carry out the procedure arrived to explain the process. Jane would be set up with an intravenous drip. A sedative would be given first. She would be asked again if she wanted to proceed, after which she would be given the medication that would end her life. It would take minutes for death to occur. Jane was told that she wouldn’t feel a thing.

“The doctor explained everything in detail in a calm tone and with compassion. There would be no surprises, no leaving us in the dark. We were all included as people who were special to Jane,” says Helen. Jane had been in regular communication with the doctor over the past few years, updating him on her condition; now he was helping her to die the way she wanted, with dignity.

After the doctor gave his explanation he told them he would be back at noon to do the procedure. They all looked at each other: that was a long time to wait. What do you do when you know you have just two hours left to live?

Jane had a playlist she’d arranged of all her favourite music and they sat together listening to Leonard Cohen, Joni Mitchell and the Beatles. The group then rugged up and took Jane outside in her wheelchair, into the bitter cold of a Brussels winter. Each of them had some time alone with Jane. “I told her I loved her, that it had been a beautiful friendship, and that I would look out for the kids,” recalls Helen.

Jane sent messages to Lucy and her parents, telling them how much she loved them all and thanking her parents for her life. Helen was also sending messages to Jane’s family back home who were waiting together at Lucy’s house for news. When that message finally came, Barbara sighed, turned to her husband and said: “That’s our little girl.” For Jane’s family, February 4 2022 would not just be a date in the calendar but forever an anniversary.

When Helen saw Jane shortly after she had died, she noticed how peaceful she looked. “She just looked asleep, her face relaxed,” she says. It was as if all the fear and anxiety of the past few years had left her.

Nearly a year after Jane’s death, on January 31 this year, the Voluntary Assisted Dying Act 2021 commenced in South Australia. It closely resembles the Victorian assisted dying law and allows people to access VAD if they are of sound mind and diagnosed with an illness that is “incurable, advanced and progressive and will cause death”, resulting in “suffering to the person which cannot be relieved in a manner the person considers tolerable”. As in Victoria, there is an added requirement that the prognosis for death must be not more than six months and in the case of neurodegenerative disease, no more than 12 months.

A total of 16 different VAD bills preceded the introduction of this law. Without its many safeguards, including a time-frame, it was unlikely to be passed. Those in support of time-frames say it ensures an enduring intention to seek VAD, and insist that a requirement of imminent death stops misuse of the law.

The South Australian law came too late for Jane, but it wouldn’t have helped her anyway. She was suffering distress well before she reached that 12-month mark. She suffered from fear of losing her ability to consent rather than enjoying the last few months of her life with her family. It is why they have chosen to share the story of Jane’s life and death. If she’d had to wait, her state of incapacity would have been severe and there was always the risk she would lose the ability to provide consent.

“Suffering cannot be given a score – it’s a person’s experience, the loss they fear, the existential distress they experience. If someone says they’re suffering, they are,” says Dr Peter Allcroft, a palliative care specialist in Adelaide. When dealing with a patient facing decline and death, timing is everything. “If faced with someone with neurodegenerative disease who had a longer life expectancy than 12 months but was clearly suffering from existential distress, and I’ve been unable to improve their quality of life with everything at my disposal, including palliative care, I would feel hamstrung.” says Allcroft.

In a situation like Jane’s, where a person wants certainty and timing, Allcroft says he would aim to ensure the patient felt supported and closely monitored for any change. He believes time-frames imposed by the legislation “provides a framework for clinicians and prevents a free-for-all.”

There are now 10 countries in the world that allow for assisted dying. Even where VAD has been available for a long time, including countries such as Belgium where there are no such time-frames, statistics show that far from a free-for-all, the proportion of total deaths by VAD is less than 5 per cent.

Stephen Kenny, an Adelaide lawyer and spokesperson for Lawyers for Death With Dignity, lobbied for VAD legislation in South Australia, having seen his own mother choose not to eat rather than continue to suffer with her disease. “I was extremely disappointed that the parliament decided on what is probably the world’s most restrictive VAD legislation,” he says. “Putting unrealistic time limits on it is not helpful. It simply means there’s a large number of people who may wish to exercise what I see as a basic human right to determine how and when they die, provided they are of sound mind. If life has become intolerable for people, why do we make them continue to suffer?”

b Lifeline 13 11 14; beyondblue.org.au

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout