‘It’s about your record’: Why Sir Tony Blair is not done yet – not even close

Seventeen years after leaving 10 Downing Street, Sir Tony Blair’s influence on world politics is greater than ever. What advice does he have for current leaders?

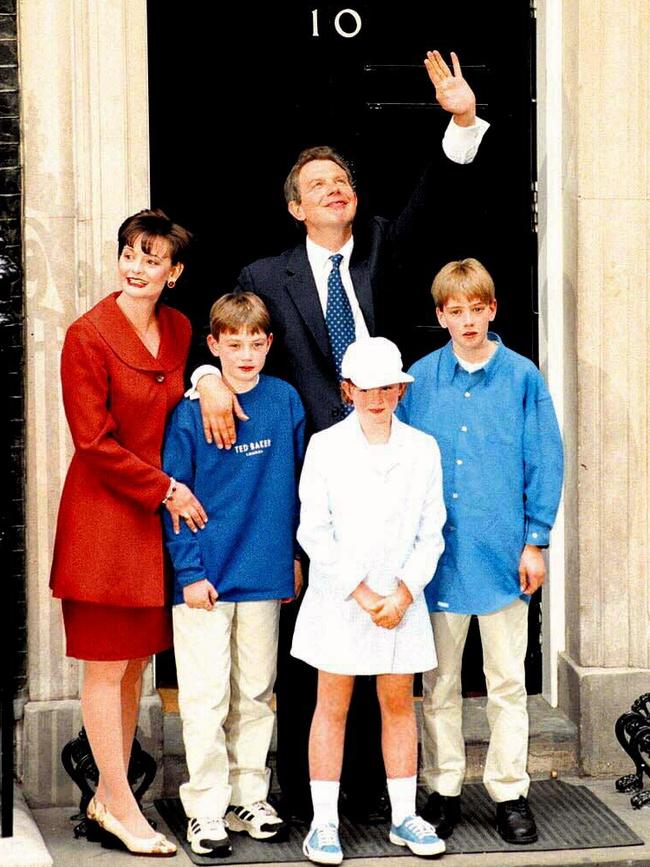

When Tony Blair led Labour to government in May 1997, he was optimistic and ambitious. “A new dawn has broken, has it not?” he said with a broad smile. At age 43, he was the youngest prime minister since Lord Liverpool in 1812. Blair was a political phenomenon, wresting his party back to relevancy after 18 years in the wilderness, positioning it in the political centre and winning a landslide election victory. His approval rating soon reached an astonishing 93 per cent in the wake of Princess Diana’s death. Ten years later, after the rollercoaster of government saw his popularity plunge and huge achievements overshadowed by a disastrous war in Iraq, he admitted it had not all gone to plan. “The vision is painted in the colours of the rainbow; and the reality is sketched in the duller tones of black, white and grey,” he said announcing his resignation. Cool Britannia was no more.

Blair transformed the British Labour Party and helped save it from extinction; as a young father in 10 Downing Street he reshaped how Britons saw the office of prime minister; he changed the royal family; and with George W. Bush he up-ended the Middle East, altering the geopolitics of the post-Cold-War world. Yet it has become increasingly clear that when his time as leader of the United Kingdom was over, Blair was just getting started. He would come to establish the not-for-profit Institute for Global Change, which employs about 1000 people and works in over 40 countries to influence policy, government and leadership around the world.

Meeting Blair in London for a lengthy interview in June last year and again via Zoom this September, he has lost none of his charm and unfailing politeness, his curiosity and zest for new ideas, or his determination to shape the world. He is disarmingly informal and persuasive. He is also reflective, as I also found when first interviewing him on the phone in July 2016. His biggest regret from his time in office is not “pushing reform further, faster” from the get-go. He is frank about Iraq and Afghanistan: “It was always going to be much tougher than we thought to implant democracy in those countries.” His single proudest achievement? The Good Friday Agreement that secured peace in Northern Ireland after generations of conflict. And he confides he sometimes wishes he was still prime minister. “A bit of you always misses it,” he reveals.

Before the age of gerontocracy, with most leaders in their sixties, seventies and eighties, Blair became prime minister when the Baby Boomers were coming of age. With his wife Cherie pursuing her own high-powered legal career, they entered 10 Downing Street with three children. Bill Clinton and Paul Keating, fellow “third way” centre-left leaders who advised Blair on his pathway to power, were also in their forties when they reached the top. “I tend to think nowadays that it would be better if I had been older, but that may just be because I am older,” he tells me. “At 53, you’ve got 10 years’ more experience under your belt.” Blair says the prime ministership is unlike any other profession: no prior experience is required. The irony is he was at his “most popular and least capable” when he started and at his “least popular but most capable” when he finished.

The Blairs had sons Euan (then 13) and Nicky (11), and daughter Kathryn (nine), in 1997. They would have a fourth child, Leo, in 2000. He was the first son of a prime minister born while in office since 1849. They occupied the larger flat above Number 11 Downing Street, traditionally home to the Chancellor, with an adjoining door to Number 10. “Having a young family is a burden in those circumstances because you should be giving time to your children and yet it is a job that really absorbs all of your time and energy and focus,” Blair, now 71, explains. “But on the other hand, I always used to say, they drive me mad and keep me sane. They were with all the problems that come with teenagers. But at the same time, there was something rather comforting about coming out of dealing with global and important issues in people’s lives and then trying to help them with their homework.”

Tony and Cherie did not arrive at their home in north London until around 6.30am on the morning after the election. With D:Ream’s Things Can Only Get Better no doubt ringing in their ears, they were hoping to catch a few winks of sleep before departing for Buckingham Place to see the Queen. When the doorbell rang before 9am, a policeman called upstairs to say there was a delivery of flowers. When Cherie opened the door to receive it, news photographers saw an opportunity and snapped her in a cotton nightie. She later said that was the moment when the reality of their new life set in. Cherie was often given a torrid time by the tabloids, and later wrote about the pressures and rewards of living in “the goldfish bowl”.

“She was a huge support, obviously, and a massive influence in a personal way on me,” Blair says of his wife, a prominent barrister and King’s Counsel. “Not as the papers used to write from time to time, you know, making up the policies of the government. But when you are in that job and you are taking decisions which are well motivated, and people are decrying your motives and saying they are done for all sorts of bad reasons, you can lurch into self-pity at some point. And she was very, very good at saying, ‘Stop whingeing. It’s a voluntary position. So if you don’t like it, leave. And if you’re not leaving, I assume you like it more than you hate it.’”

Having a supportive family can be essential for a prime minister, and so is having interests away from politics. This is what Keating calls “the inner life”, and Blair subscribes to it. Politicians can be supported and replenished by a hobby, a mental or physical place to go, to rest and relax, to enjoy life. “As a politician, you should always have a hinterland,” Blair maintains. “Somewhere you can go to that is yours, where you can zone out all the stress and the pressure. Because temperament in politics is as important a quality as any other.”

Blair would strum a guitar almost every day, read history or a crime thriller, and watch classic movies. He also tried poetry, painting (Winston Churchill’s favoured pastime) and pottery. He carved out space in his schedule to see friends who were not in politics, and family was the “heart” of his hinterland.

Before he was two years old, Tony and hisolder brother William moved to Adelaide with their parents, Leo and Hazel. Their sister, Sarah, was born in Australia. For three years, they lived in the Adelaide suburbs while Leo – who knew and was an admirer of Bob Hawke – taught law at the university. “I love Australia,” Blair enthuses. “I haven’t been there for some years, actually. I would really like to go back because some of my best friends and happiest memories are Australian. It’s a wonderful country. And I always think, you know, people talk about America and how blessed America is, but I think Australia is a pretty blessed country.”

Studying law at Oxford University, Blair met two Australians who changed his life: Geoff Gallop and Peter Thomson. “The most influential people who brought me into politics,” Blair says. Gallop, who would go on to become premier of Western Australia, was a huge intellectual influence. Thomson, an Anglican priest, fused politics with Christianity in his teachings and also had a big impact. “I started with a strong desire to change the world,” Blair says of his journey. He worked as a barrister before winning the seat of Sedgefield for Labour in 1983. Law was not for him because of “insufficient sense of purpose” and nor could he imagine remaining with his rock band, Ugly Rumours, because of “reasons of insufficient talent”.

“When I got into politics, I realised I had to change the Labour Party in order to have any chance of leading the country and therefore changing the world,” Blair says. The party had been out of office since Margaret Thatcher swept to power in May 1979.

After the sudden death of Labour leader John Smith, Blair seized the moment and became leader in July 1994; another rising star of the party, Gordon Brown, had considered nominating for leader but eased the way for him. Exuding youthful charisma, Blair embodied a new generation of leadership. He set out to reform his party, renovate its policies and embrace cutting-edge electoral techniques, which led some to disparage a shift towards media spin and marketing over substance.

Determined to move the party towards the centre, Blair worked with Brown, Peter Mandelson, Alastair Campbell and others to develop a plan to return to government. They took inspiration from Clinton’s New Democrats, and Hawke and Keating’s Labor. Blair visited Australia and met “political soulmates” Hawke and Keating when they were each prime minister. “Bob Hawke was, I thought, a politician of quite exceptional sensitivity to what I would call normal people, you know, people outside of politics,” Blair recalls. “He had a really great manner about him and was incredibly smart, actually. And Paul Keating was directly helpful to me before the 1997 election when I spent time with him. He is such a smart guy and was a wonderful help to me and gave me some very good advice on income tax, which is basically, don’t mess around with it.”

New Labour was centrist in its bearing, drawing ideas from the left and right, favouring innovation in policy, with pragmatism trumping ideology. “What matters is what works” was the mantra.

When Blair headed to Buckingham Palace for his first audience with the Queen, he was nervous. “It was pretty daunting because I had grown up with the Queen and she was this extraordinary figure in my life,” he recalls. He found her to be shy but also direct. “You’re my tenth prime minister,” she said. “Winston Churchill was the first, and that was before you were born.” That put him in his place. “I got to know her well,” he says, with some understatement. When Blair captured the mood of a shocked and grieving nation, coining the phrase “the People’s Princess” on the day Princess Diana died in August 1997, he stood in sharp opposition to the royals. He overtly emphasised “compassion” – a value implicit in British identity – and the royal family was forever changed. The Queen knighted him in 2022. In person, though, he insists I call him “Tony” rather than “Sir Tony”. One other thing: he has never seen The Queen (2006), the film about the monarchy’s crisis in the wake of Diana’s death, with Michael Sheen cast as him.

In assessing his decade as prime minister, Blair says the achievements were evident but some were quickly forgotten. The Good Friday Agreement has kept peace in Northern Ireland. The economy grew strongly, a minimum wage was introduced, and crime rates fell. The Bank of England was given independence. There were reforms to health, education and child services, with significant reductions in child poverty. Freedom of Information laws were introduced, alongside the Civil Partnerships Act, Human Rights Act and Disability Discrimination Act. Power was devolved to Scotland and Wales, the House of Lords was reformed and Londoners could elect their mayor.

Despite being Labour’s most successful leader (winning a 179-seat majority in 1997, and twice re-elected) and second longest serving prime minister after Thatcher in the past century, Blair remains a polarising figure. This was evident when I met with him last year. His office is located in an unexceptional building on a London street without any signage, no doubt to keep any remnant protesters at bay. Some Britons recoiled at the fees he earned for consultancies, speeches and writing his memoirs. But the chief reason is the Iraq War which saw the UK join the US and Australia in a post-9/11 invasion to disarm Saddam Hussein of weapons of mass destruction that were never found. A scandal erupted over evidence of WMDs and the tabloids feverishly reported on the so-called “sexed-up” intelligence dossier. Throughout it all Blair had the Messianic zeal of a convert over Iraq, saddling up with ease alongside Bush. Some voters cannot forgive him.

“I am regarded as a polarising figure in some respects, but I’ve never been a particularly polarising type of person,” is Blair’s answer as to why he seems more popular abroad than at home. “In politics, when you decide, you divide, and especially if you are there for 10 years. You just accumulate people who disagree with things.” Reviewing those post-9/11 decisions, working closely with Bush and John Howard, he says: “What we did in Iraq and Afghanistan was with the best of intentions.” He met and talked with Howard regularly. “Even though he was from a conservative perspective, I found him a really upright, strong, decent person to deal with,” Blair says.

After 14 years of Conservative government chaos and dysfunction, and a revolving door prime ministership from David Cameron to Theresa May to Boris Johnson to Liz Truss to Rishi Sunak, the Blair government is being reassessed for its length, stability and legacy. Last year, YouGov found Blair to be the least unpopular prime minister of all his successors. (They all have net-negative ratings.) Brexit has not solved any grievances litigated by its proponents but rather weakened the economy, increased business regulation, devalued the pound and worsened the budget, while goods and services are more expensive and immigration is higher. The country seems more divided than ever. Blair reckons he should have done more to articulate what he achieved in office. “I should have done much more to protect my legacy,” he says.

In his new book, On Leadership: Lessons forthe21st Century(Penguin Random House), Blair writes like a kind of motivational coach about the exercising of power. It’s full of advice on how to lead, from managing your schedule to building a team, focusing an agenda and communicating persuasively. He draws on his own successes and failures, making shrewd observations along the way. The overriding message is to be bold: if you get to the top, write your name into the history books, not the visitors’ book. The word “Leader” has a capital “L” throughout.

“The challenge for democracy is efficacy,” Blair says. “It’s getting things done. People in what I would call more conventional politics today often seem to lack a strong economic mission. And then in the world as a whole, it’s much more uncertain geopolitics that you are confronting. So, the consequence of all of that is that it’s hard to give countries the strong sense of direction that countries need if they’re going to make progress.” In other words, leaders must have a strong vision and purpose, a plan, and the fortitude to deliver.

Churchill, he says, was Britain’s greatest wartime leader. He has respect for Thatcher, who reportedly said, perhaps tongue-in-cheek, that her proudest achievement was “Tony Blair and New Labour”. He names Nelson Mandela as an “iconic” leader and Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew as an exceptional “executive” leader; he met both of them. When it comes to his own leadership, and perhaps that of others, the keys to unlocking it are found in nature and nurture. “Some of it is a willingness to step forward when other people step back, and to assume that mantle of responsibility – so to that degree, it’s natural,” he analyses. “On the other hand, you can have someone with that quality who, when they get into power, does not have the executive capability to make things happen. And a lot of that executive capability is taught – that’s where it’s nurtured.”

At a time of global economic insecurity and social division, the challenge for leaders is to implement policies that improve lives. There has been a populist backlash against immigration, trade and global investment. Blair says the antidote is not to turn back globalisation and pull up the drawbridge but to deliver results on things like the cost of living crisis. He established a Prime Minister’s Delivery Unit within the Cabinet Office to ensure his government’s highest priorities were being actioned. He recommends it for all governments, and has helped several administrations set them up.

A crucial message in the book is that technology can provide solutions. Blair is an enthusiast for Artificial Intelligence. He argues technology can make services more effective and efficient. But he is alive to risks such as disinformation, disruption and terrorism. “This is the 21st-century equivalent of the industrial revolution,” he insists. “It is general purpose technology, so you could use it for very good things and you can also use it for very bad things.” But the benefits of AI outweigh the dangers. “It is going to change the way we live and work and interact with each other,” he adds. “So, once you understand that, then the role of government is to access the opportunities and mitigate the risks. I can see how you can reimagine the state for the 21st century through technology. And, you know, for developed countries, the challenge is how do you get out of a situation where we have high levels of spending, high levels of taxation, and not very good outcomes for public services in a lot of cases. How do we break that cycle? I think the answer is technology.”

When I first interviewed Blair in mid-2016,he despaired about centre-left politics and worried that the party he’d made fit for governing was unsalvageable. Labour was then led by the neo-Marxist Jeremy Corbyn; in Australia, Labor had lost office and would lose two more elections as it jettisoned much of the Hawke-Keating legacy to embrace an old-style interventionist, regulatory, big spending, big taxing approach. While the centre-left is now in power in the UK, US and Australia, the challenge remains to not drift from the vital centre of politics.

Blair is in no doubt that Gordon Brown, who succeeded him in 2007, lost the 2010 election because his government stopped being New Labour. The pair had been friends and collaborators in opposition, then colleagues and rivals in government. There were many rows – what party communications director Alastair Campbell labelled the “TB-GBs” – and Brown was eager to succeed Blair sooner rather than later. “I’ve always had a huge respect for Gordon and for his ability, despite the differences we had,” Blair reflects. “He’s a huge intellect and was a massive and, for most of the time, positive influence on the government.”

When Keir Starmer replaced Corbyn as Opposition leader in 2020, Blair was relieved. He told me a year out from the July 2024 election that Labour would win. Starmer lacks the razzle and dazzle of Blair, but he is intelligent, methodical and determined. Although facing strong headwinds mere months after winning government, Starmer purged Labour of Corbyn and his acolytes, and moved it back towards the centre to secure victory. Labour was “on the brink of going out of existence” with Corbyn, Blair says.

Britain is not the only country to be tested by racial and religious divisions, and populists exploiting grievances. Blair notes that every country must have strong border policies with clear rules to control immigration, which can bring “cultural strain” to communities. He supports a digital ID to better enable citizens to engage with government, and it could be a “control mechanism” for immigration. (The government has ruled it out.) “The only way to prevent populism is to solve the grievance,” Blair argues. “Usually, populists don’t invent problems; they just exploit them.”

The Israel-Hamas war has sown divisions in the UK, US and Australia. Blair is reluctant to be drawn on the conflict – from 2007 to 2015 he was Special Envoy for the Quartet (comprising the United Nations, the United States, the European Union and Russia), and his Institute for Global Change works throughout the Middle East – but does hope a “hostage deal” is reached soon and the future “governance” of Gaza can be resolved which is neither hostile to Israel nor deprives Palestinians the chance of “stability” and “reconstruction”. A two-state solution, he argues, will not be back on the table until this is achieved.

Competition between the US and China, and the countries that associate with them, is the “geopolitical challenge of our time”, Blair says. But the West will no longer be hegemonic. The response of the UK, US, NATO and other democracies to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is an encouraging sign for the Western alliance framework. He says the task for Australia, like the UK and US, is to compete with and confront China where necessary but not to eschew dialogue and co-operation. Asked about the $368bn AUKUS nuclear submarine agreement, he says: “It’s not aimed at China, but it’s just showing to the world that there are alliances that are based on values as well as interests and that they’re strong.”

Ahead of the US election in November, Blair says the “politics is pretty rough” and politicians outside the US should be careful what they say about Donald Trump and Kamala Harris because they’ll have to deal with one of them. He also notes that for all the “dysfunctionality” of US politics, it would be unwise to bet against the country. “In terms of the resilience of its economy, in terms of its technology, in terms of its military superiority, in terms of the fact that it’s the world’s biggest oil producer, biggest gas producer, America is very strong.”

Blair does not presume to give advice to Anthony Albanese, who will face re-election in the next six months or so. But he does have a winning formula for re-election. “At the end of your first term, the reasons for putting the other lot out is somewhat in the past,” he explains. “So, it’s about your record, but it’s about also what you are going to do for the future. In my second election, we had this mantra: ‘A lot done, a lot to do and a lot to lose’. I think it’s the same for any government.”

It took Blair time to work out what he wanted to do after the prime ministership and how to do it. Through his institute, he seeks to influence the strategies and policies of governments. “From quite an early age, I was wanting to have a sense of purpose,” he says. “I think that’s still there and, you know, people are going to agree with what I do or disagree with what I do, but I’m never going to be retiring and putting my feet up. That wouldn’t be me. I love what I’m doing now and I feel very fulfilled.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout