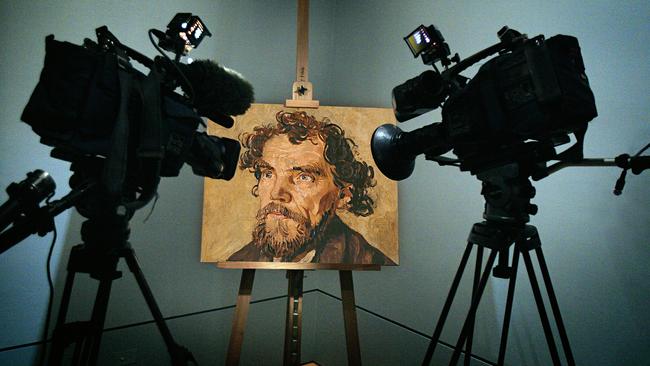

Is the National Gallery of Victoria’s Head of a Man a van Gogh, or not?

IT’S a mystery that’s baffling the art world. Is the National Gallery of Victoria’s famous painting ‘Head of a Man’ a van Gogh, or not?

IN 1880s Paris, a Ukrainian painter, Ivan Pokhitonov, was making quite a name for himself with gentle landscapes daubed during his many field trips around the French countryside.

His work was sought after by wealthy American collectors and 17 studios were vying to represent him before he eventually signed with Galerie Georges Petit, the Parisian dealership that employed Vincent van Gogh’s younger brother Theo.

Pokhitonov had been visiting the artists’ studios of Paris for a decade but had never encountered the younger, struggling artist Vincent van Gogh. At 34, van Gogh had come to painting late and his pictures were not yet considered sufficiently accomplished to be collectible. His romantic life was a series of disasters and he relied on Theo for income.

Then, in late 1886, as summer yielded to autumn, Pokhitonov and van Gogh are believed to have crossed paths in a busy Montmarte workshop on a little dog-legged street off Avenue de Clichy. The result of that encounter could be Head of a Man, one of the National Gallery of Victoria’s destination paintings, in which, according to a growing chorus of academic and amateur opinion, Pokhitonov’s face is rendered in oil on canvas by his new chum.

By this time van Gogh had painted a few self-portraits, possibly because he couldn’t afford to pay models to sit for him. In Head of a Man, pointillist brushstrokes — the style that would eventually define his technique — were becoming evident as he captured the Russian’s serious blue eyes and unkempt dark curls on an unusual landscape-shaped canvas. Pokhitonov left Paris soon after the encounter, quite likely with the portrait tucked under his arm. He lived until his 70s, dying in 1925, shortly before the first known record of Head of a Man was created in a catalogue raisonné of van Gogh paintings issued by Abels Gallery, Cologne, in 1928.

Amid growing political turmoil in Germany the picture — which by now had been cut down from its original size to 33cm x 40cm, possibly explaining the missing signature — was bought by a wealthy Jewish fabric merchant, known until recently as Collector S. He sold the painting in 1933 and as pre-war turmoil heightened, Head of a Man changed hands a further three times: from a Paris gallery to a London collector to Lieutenant Colonel Victor Alexander Cazalet, an MP for Cranbrook, Kent and London. He loaned it to a touring exhibition of French and British Contemporary Art which found its way to Melbourne in 1939. The following year the National Gallery of Victoria confirmed it had acquired the painting for £2196 with its Felton Bequest, dedicated to the purchase of masterworks.

For the next 66 years the figure with unruly locks and weathered skin stared out at visitors from his heavy frame fixed to the wall of the Melbourne gallery. The sitter’s name had been lost to the years and the gallery offered no speculation about his identity. The generic title given to the canvas also shifted: it was referred to variously as Head of a Man, Portrait of a Man and the German Männerporträt.

Then, in 2006, while on loan for an exhibition at the Edinburgh Festival, and back in Europe for the first time in 67 years, British art critics questioned Head of a Man’s authenticity. They thought it didn’t look quite right hanging alongside other van Goghs at the Dean Gallery. Art critic Frank Whitford was emphatic in his review of the exhibition for Britain’s Sunday Times newspaper: “The picture cannot be by van Gogh. The brushwork is fluent, assured and conventional. It’s of a size that van Gogh never used. Finally, and most suspiciously, nobody has any idea where the picture was until it first came onto the market in 1928.” Whitford added: “Whatever was the British art historian who acted as Melbourne’s adviser thinking when he told the gallery to buy it in 1940?”

The NGV had a problem. Authorship of the nation’s only finished van Gogh oil painting was being questioned, potentially wiping millions off its value. And worse was to come as details of the painting’s history came to light.

The gallery’s first response to the dilemma was to hold its ground. “We continue to believe Head of a Man is by van Gogh, as there is much evidence in support and to date, insufficient evidence to the contrary in the criticisms put forward,” NGV director Gerard Vaughan said at the time. “So many scholars have accepted the painting as authentic. However we have a completely open mind on the issue and are committed to getting to the truth of the matter.”

By the time the painting was returned to Melbourne the following year it had been examined by the accepted authority on van Gogh’s oeuvre, the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. Its report on the painting’s authorship damned it to an uncertain future. It noted that the “fairly coarse and detailed painting style” was not seen in any of the painter’s other works, that the composition was unusual and that there were faults in the anatomical details of the sitter’s face. “There are more differences than similarities between the portrait in Melbourne and van Gogh’s Paris and Antwerp oeuvre, and the sum of the anomalies make it plain the work cannot be attributed to van Gogh,” it concluded.

The eccentric painter rarely dated his work, didn’t have a dealer and occasionally didn’t sign pieces, so posthumous cataloguing has often been established using his prolific correspondence, most of it with Theo. There was no correspondence relating to Head of a Man, but as the brothers both lived in Paris at the time it is understood to have been painted, communication would most likely have been verbal.

Head of a Man was made from materials of the era — canvas, oils and pigments — so it was not thought to be a modern forgery. The Van Gogh Museum concluded it had been painted by another artist, even though no other works by this mysterious artist have ever surfaced. Sceptics of this theory wonder why anyone would pursue the same unpopular style as van Gogh, who did not enjoy any commercial success during his lifetime.

The NGV released a summary of the Van Gogh Museum’s report in 2007 and publicly accepted its decision. But in the bowels of the NGV’s brutalist bluestone St Kilda Road headquarters, the research continued.

Such chicanes are not unusual in the high-stakes, blue-chip art world where the top-selling van Gogh is a portrait painted in 1890 of the artist’s medic, Dr Gachet, which sold at auction in 1990 for $US82.5 million. The Van Gogh Museum’s finding resulted in Head of a Man’s value being slashed to $10,000. The picture had been valued for accounting purposes at $5 million but even in 2006 it would have been expected to fetch far more at auction. The NGV also lost a valuable loan work; old European master works can be useful trading chips when negotiating international art loans.

By December 2011, the gallery’s investigations had revealed that the previous owner, known as “Collector S”, was Richard Semmel of Berlin. Semmel had migrated from Poland and made his fortune in the rag trade, investing some of his profits in a burgeoning collection of impressionist masters and Dutch and Flemish painters of the 16th and 17th century. Head of a Man was recognised as one of Semmel’s more significant paintings. When Hitler’s National Socialists came to power Semmel fled to Amsterdam where, in 1933, under duress, he sold all his artworks through the Frederick Muller auction house. Once these details were verified, the NGV updated the provenance information on its website.

Meanwhile, the Semmel estate had been scouring the world, seeking to recover the collection. Semmel’s story is sadly typical of Jewish refugees of the Nazi era. After a couple of years in Amsterdam, he and his wife Clara fled as the Germans invaded; his brother and sister-in-law who stayed behind eventually perished at the hands of the invaders. The Semmels made it to New York via a period in Santiago, Chile. Clara died in 1945 and for the next five years Richard Semmel attempted to recover his artworks but was unsuccessful and died in penury, cared for by a family friend, Grete Gross-Eisenstaedt. He had no children and left his estate to her. The heirs are Gross-Eisenstaedt’s maternal granddaughters.

According to the principles of the 1998 Washington Conference on Nazi reparation, signed by 44 nations including Australia, artworks identified as having been stolen from Jews or sold under threat of persecution between 1933 and 1945 can be claimed with the expectation of return without compensation to the relinquishing owner. The Semmel heirs are among the highest profile international claimants of Nazi stressed sales. So far they have settled claims with private owners of two Pissarros, a Renoir, a Gauguin and a painting by Hans Mielich. Last year they were reportedly furious when a Dutch restitution committee ordered that the public gallery in possession of three of four former Semmel works had a greater interest in retaining the pictures than the heirs, who live in South Africa.

Last month the NGV removed Head of a Man from display, saying it accepted that the painting belonged to Semmel and that the heirs are the rightful owners. In doing so it cleared the way for the first Australian Nazi restitution claim.

An NGV spokeswoman says the gallery was not aware of any heirs seeking restitution when Semmel was found to have once owned Head of a Man; nor did the 1933 auction catalogue hint that the sale had been forced, giving researchers any reason to look for heirs. “The NGV’s establishment of the first provenance research website in Australia clearly shows our commitment and transparent approach to works with unclear provenance,” the spokeswoman says. “It was the NGV’s own dedicated research that discovered the Semmel link and then published the information on the website.”

The NGV’s action is commendable and timely by museum standards, given the heirs’ claim was lodged just six months ago. However their Swiss lawyer, Olaf Ossmann, said last year that the NGV should have attempted to contact him as soon as Semmel’s prior ownership was discovered in 2011. (The details about Semmel’s ownership published on the NGV website went unnoticed until they were revealed in a story in The Australian.) According to the Washington Principles, owners should attempt to contact Nazi victims if they are known.

This month NGV director Tony Ellwood flew from Melbourne to attend the contemporary trade fair Art Basel in Switzerland and to commence negotiations with Ossmann. Ellwood says the gallery would like to retain Head of a Man despite its unknown authorship, the uncertainty only adding to the painting’s fame.

Despite Head of a Man having been revalued at $10,000 after deattribution, the NGV has been happy for its current value to be estimated as $200,000. Which raises the question: is this how much the Semmel heirs will be offered? If so, Ossmann will reject it. During the year since he learnt of the picture’s connection to Semmel he has boned up on its history and is convinced the original attribution to van Gogh is accurate. He’s likely to seek a much higher figure. “Semmel bought it as a van Gogh and we know how careful he was in his collection,” Ossmann says.

Another person who is convinced of van Gogh’s authorship is Swiss art dealer Walter Feilchenfeldt, an international authority on van Gogh who spent 25 years collating a catalogue of the works he painted in France. Feilchenfeldt examined Head of a Man in Melbourne in preparation for his book, Van Gogh, The Years in France, published late last year. He left it in his book because he was not convinced it should be omitted. Despite working closely with the Van Gogh Museum on the book and accepting it as “the expert”, Feilchenfeldt made the bold decision to reject its scholarship on that painting.

Last month, the NGV released the Van Gogh Museum’s full report, having kept it secret for seven years. After reading it, Feilchenfeldt hasn’t changed his mind. His views are supported by amateur scholars Hanspeter Born and Benoit Landais, whose new book Schuffenecker’s Sunflowers and other van Gogh Forgeries claims many of the Dutch master’s most famous works are forgeries but that NGV’s Head of a Man is authentic. They also identified Ivan Pokhitonov as the hitherto unknown sitter. The NGV rejects both assertions.

Melbourne University research fellow Hugh Hudson claims the NGV accepted the Van Gogh Museum’s decision too readily in 2007. Dr Hudson is an expert in attribution and the scientific analysis of artworks; he worked for a time at the NGV, where an observer says he gained a reputation for being “too sleuthy” for the sober institution that prefers staff to toe the line. Hudson has examined the picture and continued to study it using information in the Van Gogh Museum Report. His recent requests that the gallery’s directorate reconsider its stance on the painting’s authorship have been ignored.

Hudson is cautious about Born and Landais’ observations because the pair are amateurs rather than scholars, but he believes they make some compelling arguments. The pair were the first to take seriously the suggestion Head of a Man depicts Pokhitonov, an idea first floated by The Age newspaper’s daily gossip column in August 2007 by a reader, Bill Rawlinson, who noted the similarity of the sitter to the Pokhitonov portrait on the cover of his new Wordsworth Classics edition of Dostoyevsky’s The Idiot. Born and Landais plotted the documented movements of both artists around Paris using receipts, letters and other evidence, discovering they were living within a few hundred metres of each other and would have crossed paths in the Clichy artist studios.

Hudson says: “The gallery should never have entered an agreement with the Van Gogh Museum that kept the full report on Head of a Man’s authenticity confidential for seven years.” Even so, he can understand why the gallery did this, saying the field of artistic attribution is littered with “competitive scholars, as well as amateurs but also speculators” racing to make discoveries that change the direction of artistic scholarship. “The conclusion of the Van Gogh Museum report is not persuasive but also they’ve gone on to publish further research [that] undermines their own argument,” he says.

The NGV’s former director Gerard Vaughan says the Van Gogh Museum is regarded as the world’s leading centre of expertise on the artist and it was essential that the NGV act as quickly as possible. “Subsequently, a number of independent scholars indicated they did not necessarily accept these conclusions, though the weight of scholarly opinion supports the Van Gogh Museum’s position. Every art museum in the world has ‘problematic’ pictures and it is a key curatorial responsibility to record and understand differing professional opinions. The NGV has in recent years seen some important ‘upgrades’ in terms of attribution as the result of exemplary curatorial and conservation research. The continuing debate on Head of a Man is part of this process.”

Some gallery staff told The Weekend Australian Magazine that the NGV’s backing of the Van Gogh Museum’s report could be a deliberate attempt to keep a lid on the settlement amount negotiated with the Semmel heirs. Ellwood says this claim is “fanciful, offensive and grossly misrepresents the NGV and the situation”.

If the painting is reattributed to van Gogh, the new scholarship will establish Head of a Man to be pivotal. So much more is known about its rich social history but also the painting techniques that the Van Gogh Museum scholars dismissed as “not typically” van Gogh. The painting would be reinterpreted as van Gogh experimenting with the style that made him famous, thus providing new insight into the artist’s development. Indeed, Ossmann believes Head of a Man reveals van Gogh emerging into greatness.

So what now for the yes-no van Gogh? Ossmann’s clients have so far revealed no interest in art other than in the money they can make from it. But what is Head of a Man worth? A true value can only be established by taking the picture to market but Feilchenfeldt says it must first be certified by the Van Gogh Museum. “I am not sure that Christie’s or Sotheby’s would include it in one of their important sales without a ‘certificate’ of the Van Gogh Museum. Even then it might fail to reach a ‘van Gogh price’ — in other words, the market would reject it as not being genuine,” he says.

Sotheby’s Australia chairman Geoffrey Smith disagrees. “It certainly is a very famous painting, documented as being by van Gogh for at least 80 years,” he says. “It would be very difficult to value but there are various ways a work can be presented for auction, even when its authorship is not absolutely secure.” Smith suggests the attribution “traditionally attributed to van Gogh” would work and presented thus, it would attract bidders prepared to take a punt.

Nothing is absolute in the art world. Head of a Man wouldn’t be the first painting with a future as colourful and uncertain as its past.