Inside the mind and the FNQ studio of artist Tony Clark

What led this painter to brush off the urbane art world and seek solace among the crocs in remote Far North Queensland?

The painter Tony Clark had never been north of Brisbane when he visited Wongaling Beach in Far North Queensland three years ago. It dawns on me, after flying for three hours from Sydney to Cairns, then driving a further two through a sheet of rain obscuring the surrounding rainforests and fields of sugarcane, that I have never been this far north either.

It’s a strange place to go looking for one of Australia’s most esteemed painters. His former students and friends – musician Nick Cave and photographer Polly Borland among them – tell me that he is something of a recluse who divides his time between studios in Sicily, Essen in Germany and, now, Wongaling Beach. I hear him described as a sage-like, nomadic figure who has spent decades mysteriously disappearing, usually to Syracuse, before resurfacing unannounced. His book collection – he refuses to quantify but there are thousands spread across three continents – has fuelled his encyclopaedic knowledge of art and history. The paintings from his Myriorama series – an ongoing project for the best part of four decades – were included in the prestigious Documenta IX exhibition in Kassel, Germany in 1992, hung on the walls of Malcolm Turnbull’s prime ministerial offices, and appeared on the covers of two Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds albums.

“When Tony speaks, you listen,” says photographer Peter Milne, who has known Clark since his student days at Prahran College in the early 1980s. “I’ve never met anyone who has his depth of scholarly knowledge about the history of art … I don’t know how many languages he speaks, but it’s more than he admits to. He reads these 400-year-old books, and yet he doesn’t make a big deal about it. You could go into any museum or art gallery in the world and he could give you an hour-long lecture on just about any piece of art you throw at him.”

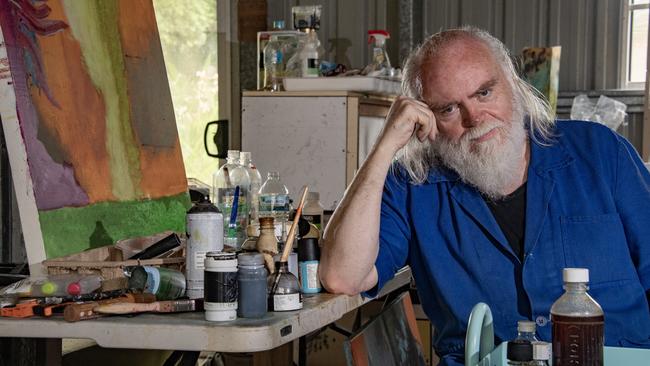

It’s mid-September when I spend three days with Clark as he prepares for his first survey show in 25 years, at Melbourne University’s Buxton Contemporary. The show’s publicist has emailed me ahead of the trip with instructions: “His studio is very close to Wongaling Beach, opposite Dunk Island, which is almost always deserted; the property is made up of two sheds – a smaller studio, and a residence with basic/rustic interiors; the mobile reception in the area isn’t fantastic. Tony will be creating a large-scale experimental painting intended to wrap the columns of the gallery for the exhibition – you’ll get the first look at this new work.” Excellent.

When I pull up in my hire car, Clark is standing in front of a shed, dressed in all black. He has a white beard and flowing long white hair. I’ve picked up some lamingtons from the Woollies in Mission Beach and apparently they are his favourites. He takes me inside his residence, which smells strongly of cloves, and I find it to be less “rustic” and more spartan. I can tell he has spent a lot of time cleaning in preparation for my visit. There is a basic kitchen with signs that he cooks (a knob of ginger, spices, and strainers of various sizes), one couch, and a chair which we place between us as a makeshift table for the lamingtons, cups of tea, and, occasionally, snuff (he offers me some; I’m tempted but decline). He tells me that in the 25 years he spent living in Melbourne he never once bought a piece of furniture. One room off the living area is stacked with thousands of books. He says it’s a fraction of the collection. He plans to consolidate all his books in one of the small properties he owns in Sicily, which he is turning into a library of mainly art books; he hopes it will become semi public.

“When you have the disease that I have, and you live in various places, and don’t drive, the books can ruin your life.” I ask him if he identifies as a bibliophile or a bibliomaniac. “I am a book slut,” he clarifies. “My inspiration comes out of books. I can justify buying any book I see.” I spy a copy of the Moscow Times from 1986 on a shelf.

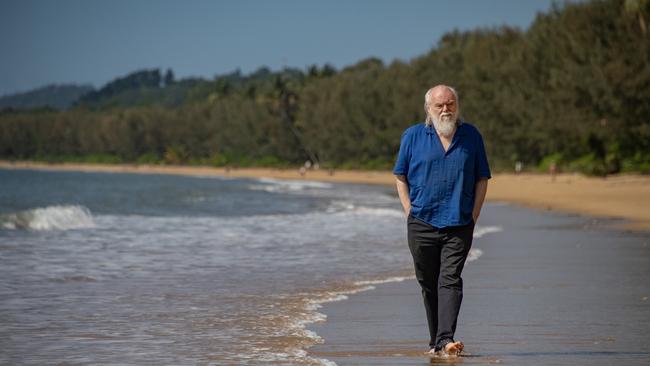

When I ask Clark, whose long history of living in Sicily dates back to a pilgrimage to the Abbey of Thelema in 1975, what brought him to Far North Queensland, he replies that the location chose him. He was back in Australia during Covid when a friend, who was looking at real estate in the area, asked him to come along. He noted that the rent was affordable, and he likes to be close to the sea. How close is the sea, I ask. Let’s go, he replies.

It will be the first of several walks I take along the beach with Tony Clark. It’s an overcast day and there is a haze across the water, partially obscuring the view out to Dunk Island. The former resort island has been closed since the battering effects of Cyclone Yasi in 2011, but it was sold for $24 million in 2022 and there are now plans to redevelop it.

“So … Crocodiles?”

“They do come,” Clark says calmly. “Usually it’s a lone male who lurks out the back.” He reassures me that someone always spots them and puts a warning sign at the entrance of the path we’ve just walked through. I look up and down the beach. It’s magnificent. There’s the suggestion of a storm that can’t quite decide if it will show up. We are the only people for kilometres. “The thing is …” I say. “Someone has to be here to spot them first?”

He agrees and then points out that driftwood, of which there is much, can look like crocodiles. Like I haven’t already noticed. We have a few of these walks together over the coming days, rarely seeing another person, me gazing out to sea, scanning for lone males. At one point Clark, who has an emollient manner, says that if a crocodile comes he will hurl himself into its jaws as he has lived longer than I have. I’m grateful and explain that deserted beaches with saltwater crocodiles are not the natural habitat of neurotic Jewish women.

He gives me a look, as though he knows a thing or two about neuroses. “You don’t have to be Jewish to be neurotic,” he says.

“Sure,” I reply. “But it helps.”

Anyone who was anywhere near the art and music scene in Melbourne in the late 1970s and early 1980s knows Tony Clark.

“In the days of the Birthday Party, Tony was the great art educator – pointing us hungry young things toward the weird, the obscure, the esoteric, the forbidden, the overlooked,” Nick Cave tells me over email. “He remains a close friend to this day, and continues to be a wonderful resource of ideas. Last month he sent me a book on Italian medieval satanic puppetry – as inspiration for my own devil ceramics.”

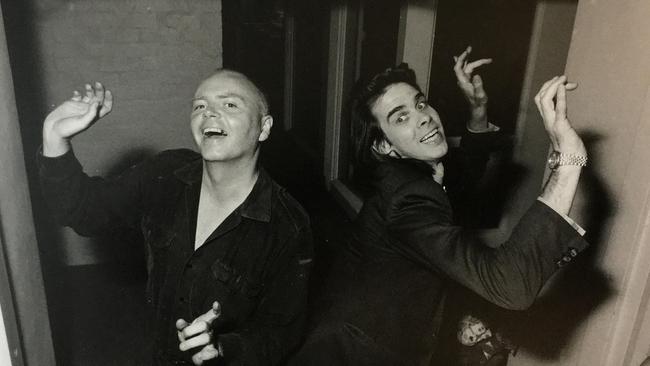

Cave’s girlfriend and artistic collaborator at the time, the late singer Anita Lane, was a student of Clark’s at Prahran College, where he worked teaching art history. Lane’s best friend, Lisa Craswell, was Clark’s girlfriend. The two couples were a striking foursome and a fixture at the Tiger Lounge in Richmond and St Kilda’s Crystal Ballroom. Another student and close friend was the elfin Rowland Howard, who was an early guitarist for Cave’s band the Boys Next Door, later the Birthday Party, and wrote their iconic song Shivers when he was 16.

“The event of the ’80s that sticks in my mind was when Nick and his mates had already moved to Berlin, and I went to see them in 1984 and just had this absolutely over the top Berlin night out which concluded with my being slightly sick and tearing up my passport to use as tissues to clean my face up,” Clark recalls. “But of course, then I had to get out of Berlin through the east with what was then an apology for a passport to show the East German guards on the train.”

“He was a mysterious, fairly aloof character,” Polly Borland tells me over Zoom from her home in Los Angeles. “Nick Cave, and Rowland Howard they all looked up to Tony. He was their teacher, kind of like the Godfather, even though he was actually a similar age.”

Clark ended up the straight man while almost everyone around him discovered heroin. “I never got involved with hard drugs,” he says. “But everybody I knew did. And that had some appalling consequences.”

Lisa Craswell and Anita Lane would eventually die from their drug addictions. Rowland Howard, who died from liver cancer at 50, had an ongoing battle with the drug. At the time of painter Howard Arkley’s death from a heroin overdose in 1999 (Clark and Arkley had a close, if at times complex, friendship) the two artists were collaborating on a project. Clark recalls a time that the painter very nearly died in front of him. “He used to conceal that he was using, and pretend that he was drunk, not stoned.” He admits that Arkley’s drug use made him furious.

There are moments, when we discuss the past, that he pauses and reaches for his snuff. He has a heavy brow, which some interpret as stern. I don’t see the sternness. I find him to be considered, gentle and kind. The furrowed brow is not dour, but thoughtful.

I ask him why he wasn’t susceptible to hard drugs when it was all around him.

“It didn’t appeal to me for aesthetic reasons, actually. I don’t like needles. There was something about the urban heroin aesthetic that I was surrounded by that I didn’t like. The culture – having to score all the time, street corners and all that stuff – just didn’t appeal to me. Mine was a more 19th-century romantic aesthetic. If there had been a Chinese opium den in St Kilda …. my God, I would have been there. But there wasn’t.”

I can’t help but make the connection between Clark’s taste in drugs and his art. It was in the late 1970s that the self-taught Clark, encouraged by John Nixon who had established the gallery Art Projects in 1979, began exploring the “anti-painting” movement.

“I was floundering a bit, not having been to art school and not really knowing what to do. But at that moment in time, as it was in music with punk, you didn’t have to have any prior knowledge or skills or anything like that. You could just get on with it. Suddenly not knowing how to play your instrument or not knowing one end of a paintbrush from the other didn’t matter that much.”

Clark’s earliest paintings were simple images of architecture. Gradually he began introducing elements of classicism as a way of re-examining the question of history through contemporary art. Paintings of classical temples gave way to focusing on the Greek temple only. His attitude was reductivist, in the pop tradition, the way Frank Stella used paint straight out of the can, or how Andy Warhol suggested that “every painting should be the same size and the same colour so they’re all interchangeable”.

His interest in classicism can be traced to his childhood. Clark was born in Canberra in 1954, but raised in Rome where his father worked for a branch of the UN. His schooling took place in what he describes as a “slightly surreal English school set up by businessmen who created a replica of their own public schools in the 1930s with blazers, caning, detention, cricket and all that abuse”. St George’s English School, set in a neo-Gothic building in the middle of Rome, was home to a wide range of children, including Liza Todd, the daughter of Elizabeth Taylor and Mike Todd; and Tyrone Power’s daughter Taryn. Clark was a doting older brother to two much-loved sisters – Judith, a curator, art director and professor of fashion, and the late Katherine, a talented jeweller who taught him skills in silverware. A spoon that he made sits on our makeshift table as an ashtray.

His last two years of schooling were at what he calls a “sort of hippie boarding school” in England, where his art teacher, a potter, was encouraging, and he went on to study art history at Reading University.

“I guess you could say that the influence of Warhol and Duchamp, which started to kick in when I was about 17, made me doubt the traditional art forms. And so I spent the next few years kind of agonising over whether there was any validity in practising art in the conventional way.

“The more you can reject things and just see what you’re left with, the better,” he says of his approach.

Indeed his approach seems to have been to reject everything, at some point or another. He soon rejected his temples and chose to focus on the landscapes that surrounded them. But his approach to painting landscapes was not in homage to the tradition of painting en plein air. Looking at these paintings, which would become the wildly successful and ongoing Myriorama project, is like looking at landscape through laudanum. The works were inspired by mass-produced illustrated cards in the 19th century that could be arranged to create a never-ending, and ever-changing landscape. After winning the 1994 McCaughey Prize for a Myriorama piece executed in a palette of four colours – light pink, light blue, raw sienna and black marker pen – Clark used the limited palette for the next ten years.

“Tony’s work, of course, is phenomenal,” says Cave, who chose two Myrioramas for the covers of his albums No More Shall We Part and The Best of Nick Cave and The Bad Seeds. “Haunting, mystical and eerily subversive.”

In a further example of his innate rebelliousness, these paintings turned away from the urban grittiness at the core of the punk scene and looked instead towards the work of his idols, 17th-century French masters Claude Lorrain and Nicolas Poussin. His oeuvre is littered with these heresies – romanticism executed with a DIY punk aesthetic. You can see the polarities in the way he lives too: the 19th-century flaneur dropped into 1980s St Kilda; the scholar in a book-lined shack in FNQ.

He sometimes refers to the Myrioramas as the M-word. Afraid of doing “romantic landscapes to order for the rest of my life”, Clark became interested in sculptural imagery. Many of the images in Unsculpted, the new exhibition at Buxton Contemporary, reflect his move away from the Myriorama as he started to think about pictorial space in a different way.

I tell him that going from his landscapes-as-fugue-state to the bold colours of the Chinoiserie series he did next is like a sensory assault. “Well Roslyn Oxley thought it was literally an assault.” He was represented by the blue-chip Sydney gallerist at the time. “She was furious. She’d set up all these punters who were just ready to part with their Myriorama money. They wanted a cheap Claude Lorrain, basically.”

Clark can talk for hours about his heroes. There are the paintings of relief sculpture by the 15th-century Italian painter Andrea Mantegna, the late works of Giorgio De Chirico, the aforementioned Poussin and Lorrain, and Marcel Duchamp, who had the female alter ego Rrose Sélavy (she appears in a number of his photographs). While researching Clark I discovered art essays written in the 1980s and 1990s by a writer named Judith Pascal, including a catalogue essay from Clark’s 1994 installation at the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art titled Some Questions Concerning Tony Clark’s Important Contemporary Sculpture. Writing about the work of Constanze Zikos in the MCA Collection Handbook, Pascal is described as a “writer and craftsperson”. A little bit of digging revealed that Clark and Pascal are the same person.

So, I ask, is “Judith” still writing? “She would love to,” Clark replies, “if only someone would ask her.” When I ask why he chose a woman’s nom de plume for his art writing, he says, “When I was four years old I told my mother that my name was Nurse Mary, so it’s not as if I don’t have form.”

The artist to whom Clark refers most is Andy Warhol. “I can’t tell you how much of a Warhol groupie I was,” he says. “To the point of going to a book signing where I got him to sign a Degas postcard because it was the most inappropriate thing I could think of at the time. Even now, with these new works, it dawns on me that I’m doing pictures of money.” The new paintings are inspired by Greek coins; Warhol, in the early 1960s, did paintings of dollar bills. Even at this late stage, the shotgun wedding of classicism and pop is all over his work.

I scan the studio, looking for what the publicist told me were the new works I’d be the first to see. There are lots of boxes. A half-painted Myriorama on the floor. I watch him paint studies of Greek coins with low relief faces on thin strips of rice paper treated with shellac. I see two paintings which he describes as “back up” inside the house, and various other studies of coins painted on the cardboard cores of toilet rolls. I don’t see any large-scale works.

“The way I actually carry on as an artist, as you can see,” he says, pointing around him, “is not some guy with a velvet beret and sable brushes. I like the pigsty approach to making work.”

The new exhibition is being marketed as an unconventional survey – the Myrioramas, for example, are conspicuous by their absence. Clark’s interest in the representation of sculpture through painting is at the core of the show, which is curated by Jacqueline Doughty and features over a hundred works taken from his archives and produced over a 40-year period. The exhibition will feature collaborative projects with artists Joanne Ritson, choreographer Shelley Lasica, mosaicist Fabian Scaunich and UK-based composer Kevin Flanagan.

In his youth Clark was famous for painting entire shows two weeks out. Sometimes he would finish the work as the gallery opened the doors. He says it used to be a mark of honour to see how late he could leave it, but assures me that he doesn’t do that anymore.

At the end of our three days together Clark walks me to my car and we say our goodbyes. I wonder if he will go back inside the studio to continue on the new works once I’ve left. As I get to the end of the street I look in the rearview mirror and see him standing in the same spot he was when I arrived, in front of his studio, watching as I drive away.

Tony Clark: Unsculpted opens at Buxton Contemporary on November 1

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout