Inside the explosive, forgotten feud between Miles Franklin and Ruth Park

Two giants of literature – one a romantic, the other a realist – were at loggerheads over their opposing portrayals of Australian life. Who was right?

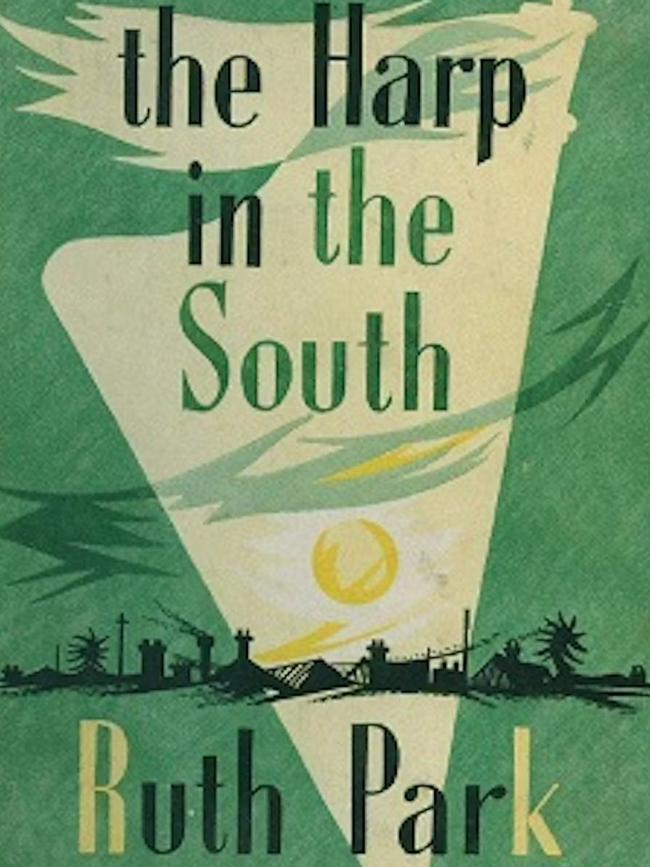

When Miles Franklin met Ruth Park in 1947, she was unimpressed by the 29-year-old who had just raked in £2000 for her first novel, The Harp in the South, set in the gritty slums of Sydney.

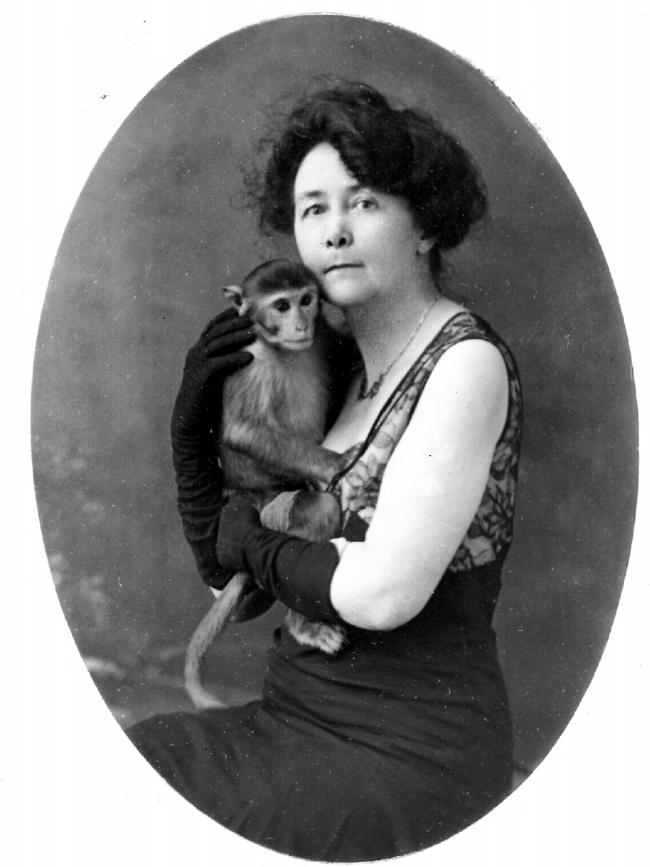

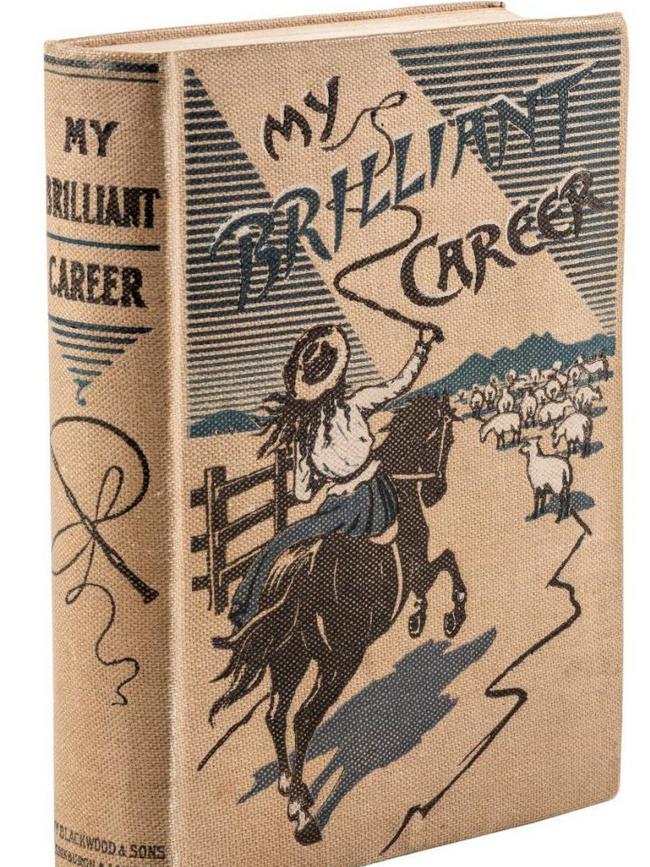

Almost 50 years earlier, Franklin, at the age of 21, had published her first novel, My Brilliant Career. She was also heavily into promoting Oz Lit – and she was politically active to boot. You might have picked her as among Park’s chief barrackers. Instead Franklin was sniffy about the overnight success of the novel about the Irish-Australian Darcy family struggling amid the squalor of Surry Hills. Franklin’s heroine, the headstrong Sybylla, whose existential crisis of freedom played out in the clean air of the bush, was popular, but after her initial success Franklin’s writing career was mixed, and she had trouble getting some later novels published.

So, no surprise that, far from embracing the young New Zealand-born writer, Franklin pronounced The Harp in the South to be phony and journalistic, and indeed a book that should never have been published. But when Park addressed the only literary group that mattered – the Fellowship of Australian Writers – in Sydney, the crowd was so big that Franklin was forced to stand on the stairs.

She reported later that Park, whose book had just won the annual Sydney Morning Herald literature prize, “is a kindly, disarming young woman, with a crown of honey-coloured hair, and that glamorised photograph in the Herald is misleading”. Ouch.

Not to mention the crowd, which, according to Franklin, “had nothing whatever to do with interest in literature, as the burbling questions and discussion showed, but only in curiosity to see a young woman who suddenly, without previous reputation, had won £2000”.

She told Jean Devanny – a writer who is now almost forgotten but was once a big name, thanks to the banning of her 1926 book The Butcher Shop, about a woman who breaks the rules of marriage – that Park “spoke brightly for half an hour, praising Australians and giving her ideas (which evidenced considerable inexperience) as freely as her experiences”. Ouch again.

Jacqueline Kent, who recounts the incident in a new book on the radical women – the socialists and communists, feminists and others who shaped our literary ecosystem between 1900 and 1970 – acknowledges there may have been some jealousy at play in this clash between two of our best-known writers. But she says Franklin’s criticism was due in part to her strong view of how the nation should be portrayed. “Miles Franklin did not like any book that trashed any aspect of the Australia that she thought she was celebrating,” says Kent. “All the novels she wrote had a particular view of Australia – a bit on the sunny uplands side.”

Indeed Franklin, who was already saving hard to ensure the literary award in her name could be established after her death, had an “insouciant voice and love of rural Australia” that ensured My Brilliant Career (made into a popular film with Judy Davis and Sam Neill in 1979) remains a crowd-pleaser down the decades.

Kent says the two classics demonstrate the interest of Australian writers in examining the lives of people within an often hostile and alien landscape – including in our cities. “I think the books that have most stood the test of time in Australia deal with landscape,” she says. “In England the great subject is class, in America it’s race, and here it’s landscape. All three of them, of course, come into all three literatures. But I do think that any Australian writing, and particularly women’s writing about landscape, will continue to stand the test of time.”

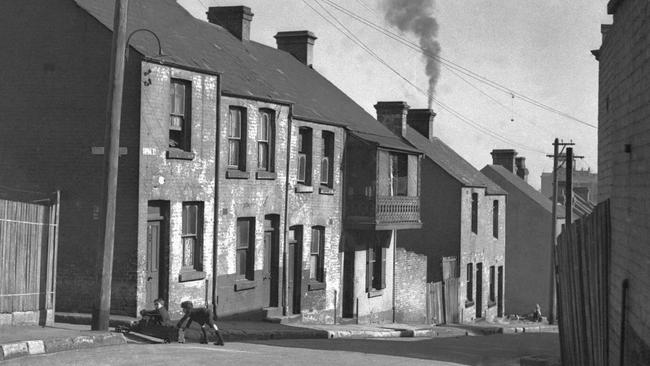

However, the landscape of a mid-20thcenturySydney slum did not play well with all of Park’s audience in that year after the ending of World War II. The novel provoked “waves of outrage”, Kent writes in Inconvenient Women: Australian Radical Writers 1900-1970.

Park, who had in fact begun her career as a journalist, was bombarded with “hate mail”. In a letter to novelist Eleanor Dark, who had in 1941 published the first book in her Timeless Land trilogy, she wrote: “I had no idea how many mental ostriches existed. You should have seen some of the letters I received in asbestos envelopes. One old boy addressed his to the Harpy of the South. I could barely look the postman in the face.”

The Dubbo Liberal newspaper summed up the no-case on January 23, 1947: “Those of the public who wanted to see Australian literature receiving encouragement and rewards only for work on the highest plane of pleasing, cultural uplift, have been sadly shaken … Literature is one of the Fine Arts. Why then is a first prize for Australian literature awarded, without comment or qualification, to a writer who reveals all too obviously to a discriminating reading public her defective educational and cultural background?” Wham.

Franklin shared her critique with others who had also survived the politics of the 1930s and 1940s – the communist Katharine Susannah Prichard, and Angus & Robertson book editor Beatrice Davis, whose power to make or break writers is the stuff of legend. Davis agreed with Franklin, deploring “Park’s frankness in describing such sordid issues as child abuse, abortion and prostitution”. A gentlemen’s agreement with the Herald prize meant that Angus & Robertson had to publish Park’s winning novel in 1948, but it “extraordinarily” did little to promote it, Kent writes.

The novel that took second prize was Jon Cleary’s You Can’t See Around Corners, which was also set in the slums – albeit with petty criminals, not working-class Catholics, as the protagonists. No one seemed to worry when Cleary’s work, like Park’s, was serialised in the Herald. Park suggested that it was because she was a woman and not Australian-born. “My novel had to [be seen] as either misrepresentation or derogatory criticism,” she wrote in her 1993 autobiography Fishing in the Styx.

She had lived in Australia for only five years, having arrived after a pen-pal relationship with the handsome writer D’Arcy Niland. They married in St Peter’s Catholic Church in Devonshire Street, Surry Hills, just three weeks later. Their relationship had been encouraged by nuns who backed the young Niland – who’d grown up in hardscrabble outback NSW around Glen Innes – to pursue a writing career in the city. The young marrieds travelled for a year in the bush – he worked as a shearer, she worked as a cook – gathering material, then took a flat with no bath and no gas above a shop in Surry Hills. They were convinced they could support themselves financially from their writing – something which most of the women in Kent’s book were unable to do, despite their diligence and talent.

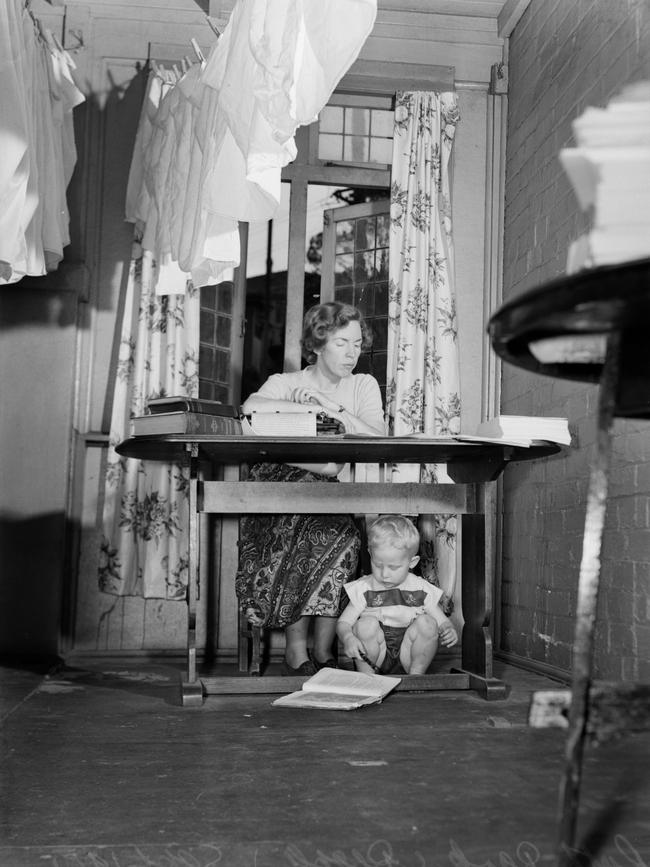

Theirs was to be a unique – and prolific – writing partnership, one able to support their five children. Niland wrote about 400 short stories and several novels, the best-known being The Shiralee, Call Me When the Cross Turns Over, and Dead Men Running. For years the couple wrote on demand, churning out short stories and radio scripts at a furious pace, with Park on a deadline with the serial The MuddleheadedWombat. She wrote many children’s books and a sequel and a prequel to The Harp in the South. They were often pictured in newspapers tapping away at their typewriters in their home on Sydney’s north shore. (It’s a whole other story, but D’Arcy scored the desk while Ruth usually had to make do with balancing her typewriter on the ironing board.)

Park is among 28 women writers featured in Kent’s book. Their writing lives are described in the context of big global events of the 20th century – Bolshevism, Depression, Fascism and the Cold War. Not everyone was a paid-up member of the Left but many shared similar hopes and dreams. Some, like Ethel Turner (Seven Little Australians), didn’t have an “overtly socialist political bone in her body” but plenty did, finding a voice in the left-leaning Fellowship of Australian Writers or the Communist Party of Australia.

But Kent warns: “You have to be very careful of labels here because most of them, even those who said they were of the Left, would have supported Bob Menzies, because the Labor Party during this period was very much a lower-middle-class, working-class party.”

She writes that several – including Prichard, Devanny and Dark – were actively tracked and pursued by ASIO during the Cold War. Along with civil rights activists Faith Bandler and Kath Walker, these women were brave, Kent argues. They were curious, fearless risk-takers – with their lives, their relationships and their work. Many juggled a literary career with motherhood.

Franklin did not have children to juggle but she spent 20 years outside Australia, and away from writing, working in organisations such as a women’s trade union league and a housing council, as well as serving as a nurse in the Balkans during WWI. She returned to Australia permanently in 1932 as “an accomplished networker, a supporter of literary journals and an encourager of young writers,” Kent writes. Single, she lived in a cottage in the south Sydney suburb of Carlton and dedicated herself to public literary activity.

Kent says she became “very fond of Miles” as she read her way through Franklin’s papers during her three years of research for the book. “She was enthusiastic, and she was emotionally available to her friends. In her letters she gives a very interesting running commentary on how things were, on her views of Australian literature and how it panned out. I think she regarded herself as a commentator on Australian literature, and [she was] a hugely entertaining one. In fact, the best of her writing is in her correspondence.”

Like so many writers of the time, hers was not a lavish life. Says Kent: “There’s a very nice, touching chapter in my book about Beatrice Davis actually, where she goes to visit Miles and Miles and says things like, ‘Well, I can make you an egg custard, that’s one dish without trouble, and I can lend you a pair of clean pyjamas if you want to stay over.”

Kent, who has written several books on Australian literary figures, says she wanted to fill a gap with this new one: there’s plenty of material on the suffragists of the late 19th century, and plenty of work on the Vietnam-era feminists, but not so much about the generations in between. These were the “bright, articulate and committed women who went through two world wars, endured a massive economic depression, saw the rise of fascism and communism and so many other changes – some catastrophic in terms of world history – between 1900 and 1970”, she writes.

There are plenty of biographies, literary analyses and memoirs of and by the women writers of this period – including Ethel Turner, Dymphna Cusack, Nettie Palmer, Kylie Tennant, Henrietta Drake-Brockman, Mary Gilmore, Dorothy Hewett, Christina Stead and of course Prichard, Park and Franklin. “But they seem to me to give insufficient emphasis to the cultural and political as well as literary background that those women worked in, and that’s what I wanted to fix up,” says Kent.

Park was not especially political. She told the Sydney Literary and Debating Society in 1947 that she had not intended to write propaganda against slums: “I was just as horror-stricken and unbelieving when I first went to live in Surry Hills. I could hardly believe such conditions could exist in a civilised country. I hated the environment and I still do. But it was not because of the locality that I wrote my novel. It was because I came to love the people, found humanity there, and felt I had to write about it all.”

The Harp in the South prompted community anxiety about the slums, many of which were soon pulled down by the authorities. Park had mixed feelings: “Not everyone was convinced of the need for slum clearance, even in the slums themselves. Most people I met were third-generation slum dwellers and most of them had so adapted themselves to mean conditions that they did not wish to leave. A great many mothers in the basic wage families longed to get away, but a great many of the fathers did not.”

If Park was an accidental – even an unhappy – activist, most of the other “inconvenient women” of the book’s title were not. As Kent notes: “In their novels, plays and poetry these women writers fearlessly tackled subjects that had always been the province of men. They might have saved themselves endless trouble by tailoring their work to the market for popular ‘women’s’ fiction, but they were not interested in that.”

Inconvenient Women: Australian Radical Writers 1900-1970 is published by New South

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout