Inside the risky lives of gold rush sex workers

Males outnumbered women in Victoria by a fair margin in the 1860s, meaning there were for many men, no potential romantic partners. Papillon catered to some of their desires.

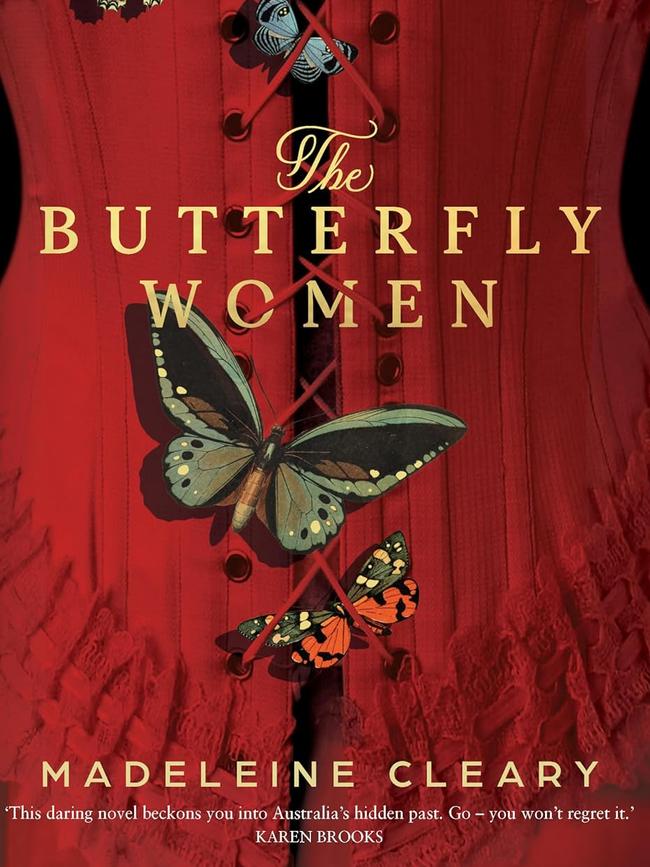

A little over 10 years ago, Melbourne novelist Madeleine Cleary discovered that her great-great-great grandmother, Catherine “Mother” Cleary, had been a “common colonial prostitute (in) Melbourne’s back slums.”

Her discovery inspired her towards her debut novel, The Butterfly Women, which depicts the lives of women working at a fictional inner city Melbourne brothel, Papillon.

The book is set during the gold rush of the 1850s and 1860s, a time of major social, cultural and economic transformation. The story that Cleary tells is necessarily gendered. Based on the 1860 census, males outnumbered women in Victoria by a fair margin, meaning there were for many men, no potential romantic partners.

Papillon catered to some of their desires. The brothel is overseen by the wily, self-possessed Madame Catherine Laurent, who acts as matriarch of a close-knit “family” of women attempting to eke out a living.

Cleary’s take on sex work is non-judgmental. She also makes clear that not all sex workers were engaged by the upscale parlours. Many took their chances in Melbourne’s dark, dangerous back alleys, risking their lives to support themselves and their families. Her depiction of both parlour and street workers seeks to destabilise the perception of prostitutes as incorrigible, unmarriageable and a corruptive societal force.

Absorbingly written and impeccably researched, Cleary’s story threads together triple narratives, blending elements of historical, crime and mystery fiction to tell the story of the so-called “butterfly women” and those around them.

The novel opens with the death of one of the city’s sex workers. It is an event narrated from the perspective of a serial killer operating on the city’s streets, soliciting women in alleyways and coaxing them from brothels in order to brutally murder them, clip a lock of their hair and dress them in finery before disposing of their bodies.

His presence in the community of working women gives Cleary’s novel narrative tension and drive. The fear he elicits is ever-present for the women and his identity is cleverly rendered unclear until the last chapters. On the way to the thrilling conclusion, readers will meet Johanna Callaghan, a recently arrived Irish immigrant, who is found bleeding on the cobblestones by Mary Jenkins, who often dons her drunkard policeman husband’s uniform in order to covertly undertake his duties.

“This is my husband’s uniform, but I ‘personate him when he’s indisposed,” she says. “In the dark, from afar, no one can really tell the difference. But of course, folk around these parts know me well. They call me Constable Mary.”

Brigitte Bannon, Laurent’s most popular employee and second in charge, engages Johanna as a domestic servant (and later for sex work) at the Papillon. While there, Johanna meets a regular visitor, Cambridge University-educated surgeon Henry, who is the brother of British police magistrate William Gardiner, and his sister, Harriett, an aspiring journalist whose ambition is curtailed not only by social conventions but also by her overprotective older brothers.

Harriet is writing ladies fashion and social gatherings for the society pages of The Argus, Melbourne’s leading newspaper, but soon starts investigating the murders of sex workers. She enlists Johanna’s help, and defies her brothers by leaving the house at night while wearing a disguise.

Throughout the novel, readers are introduced to each of the women who become murder victims, offering a glimpse into their lives and their last moments on earth.

Cleary adroitly combines historical research, women’s interactions with the legal and justice systems, and their daily battles as daughters, wives, mothers and workers, to offer compelling glimpses of their existences not as two-dimensional characters but, rather, fictional representations of the fully complex and animated human beings that inspired their creation.

The Butterfly Women is deeply researched, but it triumphs primarily as a dextrous, sympathetic exploration of women’s changing roles in society. It portrays inter-class relationships and friendships with tenderness and emotional insight while retaining an awareness of the class and gender barriers that worked vociferously against their success.

Heidi Maier is a writer and critic. This is her debut review for the Books pages

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout