‘I felt torn between maintaining the nurses’ memory and finding out the truth’

In February 1942, 22 nurses were ordered onto the beach and executed at Bangka Island. Only today are their relatives beginning to learn the full details of the women’s tragic fate.

I fell into Bud’s story, I think, if I’m honest. There was no hero’s journey, no desperate discontent. Maybe my gradual uncoverings began with a murmur from the other side of the grave. Or a crack in the family silence when Dad lent me a book about the massacre of wartime nurses on Indonesia’s Bangka Island and awoke my curiosity.

Perhaps those events of February 1942, when 22 nurses walked into the sea off Radji Beach knowing they were to be shot by Japanese soldiers, were always in my bones. And it was time, 75 years later, to open the door to our family history. It was close enough that Bud’s nephew, my dad, and her niece, my aunt Sally, were still alive. Not so close that the grief would envelop you. Though at times I felt it did.

When amateur historian Michael Pether wrote to me in Melbourne at the end of 2016, Bud was barely on my radar. Michael told me that a 75th memorial service of the massacre on Radji Beach was to be held there the following February. He was trying to write the memorial entry on my great-aunt, Dorothy Gwendoline Howard “Buddy” Elmes. He’d found her in a blog I’d written, in which I had mentioned her name once, in passing.

The blog was about resilience and my grandmother, Jean. In a few short years Jean had lost her sister Bud and her husband, Arthur Rowland Banks, who was known to us all as Dolly. Both in traumatic circumstances: not long after the family found out that Bud was likely dead, Dad’s father, Dolly, went missing for a week and turned up dead in the Yarra River. It was said to have been a heart attack, but Aunt Sally thought it wasn’t. “Cause of death: Drowning (open)”, the death certificate read.

When Michael’s invitation to the memorial arrived, I was interested – how could I not be? –but I was busy, working, running a learning and development consultancy. Two teenage girls to look after. Then again, this was an invitation to wrest myself from my usual routine. To retrace my relative’s steps, to find out more about a story of national significance, of women in war, that seemed not well enough known for my liking.

Bud had travelled north from her home in Cheshunt, Victoria to Corowa in NSW aged 21 to be trained as a nurse. Then the call of duty came – she was very keen to sign up for active service, her great friend Jean “Smithy” Smithenbecker had said. Appointed to the Australian Army Nursing Service in November 1940, Lieutenant Elmes departed Sydney Harbour on the Queen Mary, on 4 February 1941, as the band played Auld Lang Syne and The Maori Farewell. She did not know her destination.

In fact she was assigned to a unit known as the 2/10th Australian General Hospital, which was stationed first in Malacca, Malaya, but her last letters to Smithy and to her parents were from Singapore in February 1942. Bud was among those who had washed ashore on Bangka Island, from some 100 or so vessels (around twenty made it to safety) that left Singapore between 11-14 February 1942, as it fell to Japanese Forces.

There were 65 Australian Army nurses who left Singapore on the S.S. Vyner Brooke hoping to make it home. 12 died when the ship was bombed and sunk. 21 were killed in the Radji Beach massacre (22 were shot but one, Vivian Bullwinkel, survived). 32 women were interned in the camps on Bangka Island – (including Muntok) – and Sumatra. 31 of them had landed in a different location on the island, thus avoiding the massacre, and the 32nd woman interned was Vivian. Eight died over the next three and a half years.

Only 24 made it back to Australia at the end of the war. Vivian was the only nurse to survive both Radji Beach and the camps.

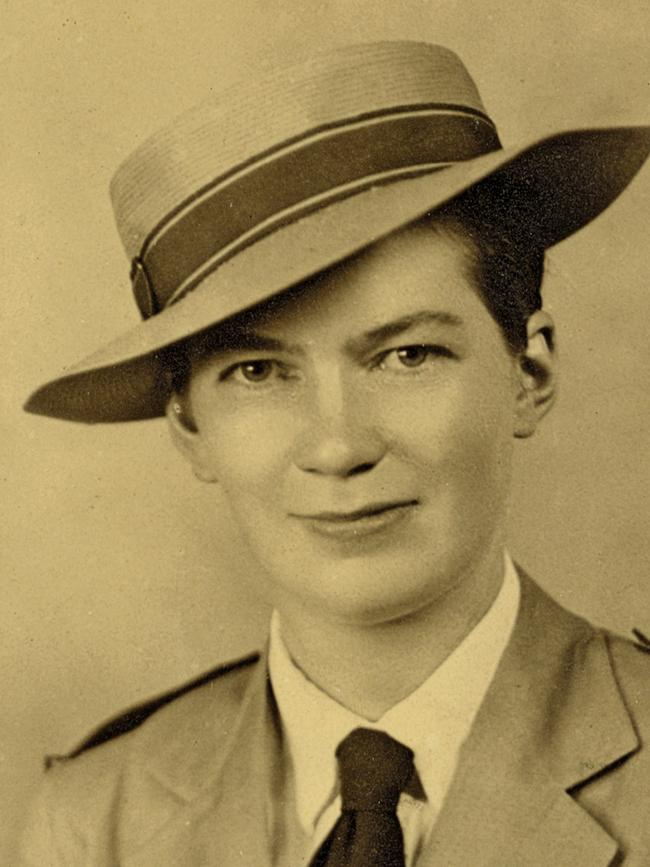

The email I had received in November 2016 contained a Facebook link: “Muntok Nurses and Internees”. I clicked it. Up came photo after photo of nurses, in black and white, or sepia tones. The images took my breath away. The page was like a shrine, a public eulogy. I scrolled and scrolled, searching for Bud.

There she was. It shocked me, though, brought me to a halt when I realised that I had never heard my grandmother mention her sister Bud’s name. Not once. I leant in to the image on the screen and took a closer look. Bud was handsome, chestnut hair pulled back in a bun, hat set at a jaunty angle. She looked a little rakish, androgynous even, in her uniform. Her eyebrows and fulsome gash of a mouth arched up, as if to challenge, are you up for it?

I needed air, so I headed down St Kilda Road, towards the Royal Botanic Gardens. Across the road was Victoria Barracks, sombre, bluestone and covered in ivy. My inner-city sanctuary was surrounded by monuments of war. A cannon sat centre stage on the lawn. I imagined Bud, a knock away from enlisting. All those nurses who wanted to do their bit, signed up for King and country. Dead in the water. Brutal, senseless violence – it was hard to take in. Back I looked towards the Shrine of Remembrance. It was easy to eulogise heroes here. But if I went to Radji, my feet would be walking where they were slain, my toes imprinting the same sand.

I didn’t want to go alone. This was an experience to be shared, preferably with Aunt Sally or Dad. In the end no one could come: Aunt Sally would need a wheelchair on the beach and it would be too hot. Uncle Clive, my sister Imogen, cousins Tim and Alex, weren’t available, my mother had no current passport. Dad said, “No. Don’t want to open old wounds.”

A couple of days later, my husband Kingsley’s sister, Amanda, who is also a nurse, called. “I’ll come, if you want me to.” I emailed Michael. “Yes. I’m in.”

Not long before my trip, Sally came over and gave me Bud’s letters and related documents. She appeared reticent but there was a sense of unburdening as she handed me this most precious of gifts. “I’ll look after them,” I promised.

The folder was heavy; I clutched it awkwardly, felt its weightiness in my arms and wondered what I was accepting. Was this a passing of the baton?

“She was a character, you’ll see,” Sally said. “Used all these funny names. ‘Old Tumpy’ for her mum, ‘Nifty’ for Jean and ‘Old Tripe Hounds’ for her friends. Real jolly hockey sticks type stuff. Old fashioned … colonial. You can’t believe they used to talk like that.” “Dear Old Nifty”, the first one started. I smiled. The next one I read through its plastic protection: “Dear Old Tumpy”. The first few were addressed to Willow Cottage in Cheshunt, where Bud’s parents had lived. At the top right-hand corner of the letters was the address of Corowa Hospital, where Bud trained and nursed before she signed up. Scrawly handwriting, almost indecipherable in parts. It tended to deteriorate as the letter went on, as if she was in a rush.

Keen to read one about the war, I leafed through pages. Found one. No date on it except Saturday. “Got a wire from Sydney yesterday saying to bring my own uniforms I have been wearing as I start duty on Tuesday.” And just like that she announced her starting date to her parents. How would they have received the news? A chasm of pride and unease opening up inside? Dread crept over me as I read, knowing the fate of the author of these fragile pages. It settled right up under my ribs, where it spread out and made itself at home. Shopping lists and mundanities filled the rest of the page: uniforms, sponge bags and hankies, plus social chitchat about people the three of them knew. I pictured Bud as she packed for war; ticked off her list, folded uniforms – or maybe scrunched them in her case – and made decisions about what she would need in an unknown destination: tennis clothes – Dad had said she was an excellent sportswoman – and a couple of dresses.

The last letters were from Singapore on February 8, 1942 – “am on duty 12 hours a day and don’t get time when I get back to write” and “at the moment we are sitting round (the operating) theatre both writing with two hurricane lanterns wrapped around with blue paper as it’s supposed to be a black out”.

By the time I read the telegram sent to Bud’s parents by the Red Cross, it was one in the morning. On 23 June 1944, Vera Deakin White (the director of the Red Cross Bureau for Wounded, Missing and Prisoners of War) wrote, “It is with deepest regret that we heard that your daughter – NXF70526 S/ Nurse G. Elmes, is now officially believed to have been killed on or after the 11th of February 1942.”

February 16, 2017, Radji, Bangka Island, Indonesia. Dismounting the four-wheel drive, I shook my bones back into place and hurried down the track to the shore. I wanted to spend some time here alone, take everything in ahead of the other relatives who had come to mark the anniversary. The jungle track ended where the brown mud met sand and the trees opened up to the heavens. I stopped. Took a step. Placed one Croc onto the sand. My skin touched Radji through navy blue polymer and I paused, waited for a feeling to hit me. But I didn’t feel it. Nothing. Instead, I saw a pretty, crescent shaped beach fringed by jungle and palms. A rocky outcrop punctuated the southern end.

We arranged ourselves on the sand, dignitaries at the front, in a horseshoe shape, relatives clustered together, staring straight ahead. The nephew of another of the nurses, Michael Noyce, spoke, then the roll call of honour was read and we moved in unison to pick up the wreaths and lay them in the sea. I held Bud’s, full of chrysanthemums, braced myself to go in. There was comfort walking shoulder to shoulder, floating our offerings. I wished my father, aunt, grandmother and great-grandparents could stand on this sand. Steeling myself at the edge, I dug my toes into the shallows.

Water touched my ankles and I winced. Deeper we waded into the sea, which lapped lukewarm against our calves. I hoped the wreaths would float freely, unhindered by the currents, and not wash back to shore as the nurses’ bodies had.

Finally, with a push, I released Bud’s wreath. And as they were let go, I felt the sadness of my family, heavy in my bones. Knee-deep, the hem of my dress now wet, I turned to look back at the shore. I could see the nurses on February 16, 1942; their grey uniforms, their Red Cross armbands, their looks of utter disbelief. Shots rang in my ears, the sea turned to red, and one by one the nurses fell.

Not long after I returned home, Michael Noyce sent me an article about Vivian Bullwinkel, written by journalist Tess Lawrence, that was released three days after the 75th anniversary. Tess had met Vivian on several occasions before her death in 2000. Vivian had told Tess that she felt “she was allowed to live so that she could be a messenger”, that there were “two things she was keeping secret for the time being” – but “there would be a time she was going to speak publicly about them”.

Firstly, she told Tess, “before the massacre on Bangka Island, Japanese raped nurses”: in Vivian’s words “most of us” had been “violated”. Secondly, she said that she was ordered by the government not to speak of any of it, which caused her much distress as she had wanted to put it in her statement at the War Crimes Tribunal, where she had testified in Tokyo in 1946. (No one was ever prosecuted for the Radji Beach massacre. The commander of the battalion that carried it out suicided in prison in 1948 while awaiting interrogation for war crimes.)

Vivian visited my great-grandparents after the war, as she did many of the nurses’ parents. Dad remembers the visit and the sadness, though he was a young boy. He told me he had a “vague memory of Mummum [his grandmother, Bud’s mother] and Vivian sitting at the dining table having afternoon tea and talking, and of course I wasn’t part of the conversation. I can remember a general sense of worry about Bud’s welfare and whereabouts.” They hadn’t heard anything from, or of her, for a couple of years until the bad news arrived.

How many times did Vivian recount her tale, each time perfecting the narrative of bravery and heads held high? And at what cost to her? Every time she sat and had tea with bereft and disbelieving parents, she must have felt the guilt of the survivor and the weight of her calling as the messenger. How did she choose which narrative to tell? The real one? The one that would protect the families from further suffering? Or the one she was instructed to relay? Who could blame her, given the stigma at the time, the shame, and – if this was true – the pressure not to speak. Offering a better version of the deaths may have been her ultimate gift to relatives.

I, too, felt torn between maintaining the nurses’ memory as Vivian had told it, the official story, and finding out the truth. Some of the relatives of the nurses were adamant that we shouldn’t talk about it. “Can’t we just remember them as they were,” one said to me, “heads held high walking into the water?”

I did not wish to bruise their memory either, I was desperate for it not to be true. But it is already out, I thought, whether we like it or not. Look around, I felt like yelling, we have royal commissions, #MeToo, Harvey Weinstein in the dock. Does staying silent protect the victims or the perpetrators?

Especially all these years later, when social mores regarding rape have changed: the stain of shame – a fate worse than death – no longer on the victims. Or was it ourselves we needed to protect? I was a generation further on, I reminded myself, from the most involved relatives of the nurses. Had not lived through the primary grief and trauma of a sister who left, a child not returned, an aunt gone missing. I had extra decades of buffering. Nonetheless, I was churned up – felt the pull in equal measure: to stay silent and live with what was starting to appear as the comfort of a lie, or pursue truth at all costs? Who owned this information anyway, these stories of the past? The nurses, relatives, historians, the public?

In April 2019, Lynette Silver’s Angels of Mercy: Far West Far East was published. In it, she categorically stated there was evidence that the nurses were raped before they were forced into the sea. I’d waited so long for this to be corroborated – or to be able to prove it myself – and there it was. Some instinct in me and my own research had left me with the position of “I think it’s true but can’t prove it beyond the balance of probabilities”.

The collective unconscious had awoken. The first sign had been Tess’s article. That was the moment it hit me with full force, knocked me horizontal, dried out my tears. Since then I had been searching, scratching around for proof one way or the other. Trying to plug holes in time, in manuscripts, in memory. Lynette Silver had, it appeared, pulled the clues together; woven them tight. Though it happened in the past, the past is still with us, as unfinished business. If we could only have an acknowledgment of what happened, specifically, to our relatives, it would make a difference, in some way. As salve to a wound. As a line in history.

I was at last able to visit Bud’s family home, Willow Cottage, in Cheshunt, two years later. When I left, I knew I would never stop trying – to get information out, to get an acknowledgment and work with the families of those impacted by these terrible events to make a mark in history. I also knew that I was leaving lighter. That some of the grief handed to me was staying here. Piled up with the rocks on the river bank, draining back into the gurgling King River, thrown out into the flood plain, and laid down beside the old oak tree. And I could picture Bud roaming the landscape, her physical prowess, her long striding walk. b

Postscript: In February 2022, press reports of the 80th commemoration of the massacre noted the nurses were raped before they were murdered. Some of the families are still pursuing official acknowledgment. This is an edited extract of Back to Bangka: Searching For the Truth About a Wartime Massacre by Georgina Banks (Penguin Random House, $34.99) out Tuesday.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout