How did we get so hung up over nuclear energy?

It should be straightforward: Australia is the only top 20 country to reject nuclear power amid a battle to find clean energy. And yet the debate causes a meltdown. How did we get here?

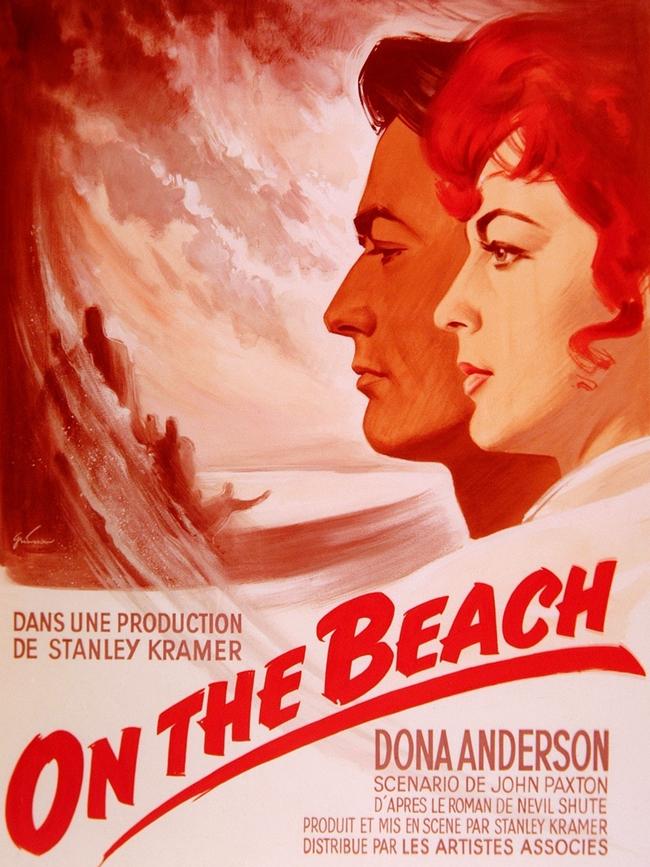

The 1959 movie On the Beach is likely one of the saddest movies you will ever see. There’s the usual Hollywood take on a poignant love story between Ava Gardner and Gregory Peck, who puts honour ahead of amour, but that’s not the reason the Stanley Kramer-directed film is so tragic. Rather, it’s the inevitability of the end of the world, thanks to nuclear war, that leaves a viewer with nowhere to go emotionally.

It was, incidentally, filmed in Australia, with some of Hollywood’s biggest stars landing in Melbourne for the shoot. On the Beach, based on the Nevil Shute novel of the same name, tells a story set in 1964. Atomic war wipes out humanity in the northern hemisphere; one American submarine finds a temporary safe haven in Australia but it gradually becomes clear that all humanity is headed for extinction.

The film shocked audiences, which was what Kramer set out to do – so much so, though, that the film ultimately flopped at the box office. But if Western popular culture wasn’t ready for On the Beach, it would catch up over the decades that followed with a canon of movies, TV shows, books and music based on the fallout of the bombs built in Los Alamos and dropped on Nagasaki and Hiroshima in 1945, and the nuclear arms race that followed.

How much of this art informed Australia’s stance on nuclear power? As a soundtrack to history, popular culture has had a powerful role to play, alternately forming and galvanising our position. There were, however, other factors at play and it all adds up to how Australia became the only Top 20 economy without nuclear power – as the spectre of mutually assured destruction became enmeshed with attitudes to nuclear-generated power in hearts and minds.

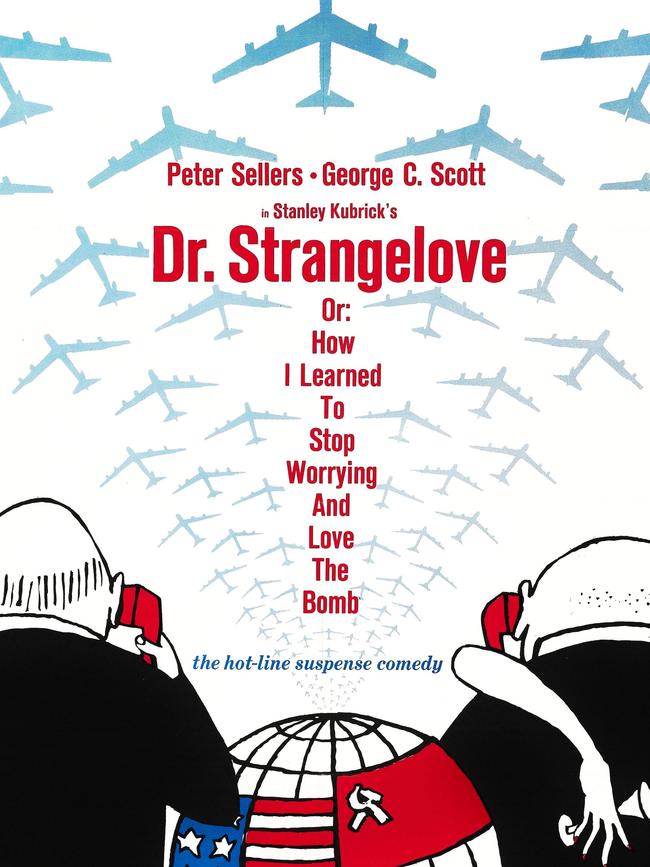

Among the highlights of the armageddon genre were Barry McGuire’s 1965 song Eve of Destruction; the 1964 movie Dr Strangelove; The China Syndrome in 1979; Cormac McCarthy’s 2006 novel The Road; the 2023 Christopher Nolan film Oppenheimer; and the John Adams opera Doctor Atomic.

Twentieth century dramas like the Cuban missile crisis in 1962 and the accidents at Three Mile Island in 1979, Chernobyl in 1986 and Fukushima in 2011 at various times reignited fears not only about nuclear weapons but nuclear power generation, too. And all the while, movies transformed the unimaginable, the unknown, the unthinkable, into the realm of the possible. The result was that for Baby Boomers growing up during the Cold War, anything labelled “nuclear” was considered almost unmentionable.

The 1950s and 1960s were a time when Britain could test nuclear weapons in our backyard – at the Montebello Islands off Western Australia, and in the South Australian desert at Maralinga and Emu Field – and at the same time use that data for educational films explaining how to survive a nuclear bomb. (Like the American “duck and cover” films of the time, the British films avoided the obvious Catch-22 – that protecting the West could also mean wiping it out).

Patriotism overcame doubts about the safety of the tests as politicians and the media promoted the idea that we were special because Britain – at that stage excluded from US atomic programs – had chosen us to help it build its nuclear capabilities. The enthusiasm didn’t last.

Attitudes to nuclear power would harden in the coming decades as feelings morphed from patriotic endorsement to fear and anger. Ultimately, Australia would diverge from much of the developed world on the question of nuclear power for reasons to do with our place in the world – our Pacific geography and the legacy of the British nuclear testing. Along the way, popular culture would play a constant role.

“The bomb” had long been part of the movie vernacular, with films like The Beginning or the End, depicting the history of the Manhattan Project, which was released in 1947. The movie underscored the political narrative of the time – that dropping the nuclear bombs on Japan had been crucial to ending the war in the Pacific. A couple of years later, in 1949, Americans were taking the bomb so lightly that the early rock band Bill Haley & His Comets were able to record Thirteen Women (and Only One Man in Town), which joked about the nuclear holocaust. Last night I was dreaming / Dreamed about the H-bomb, Haley sang, before describing the joys of a world in which most male rivals had been exterminated.

Things began to flip with the counterculture movement of the 1960s, with its protests about politics, power, capitalism, the Vietnam War and the System. It was into this mix in 1964 that Stanley Kubrick’s avant-garde Dr Strangeloveor: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb landed. By the 1970s, as the arms race gathered pace, popular culture began to focus more directly on the nuclear threat.

No Nukes, the 1979 triple live album based on the protest concerts in New York’s Madison Square Garden, featured singers like James Taylor, Bruce Springsteen, Ry Cooder and Carly Simon. In Melbourne, the Sidney Myer Music Bowl hosted a concert called Stop The Drop in 1983 to raise money for People for Nuclear Disarmament; the biggest names in Oz rock – Midnight Oil, INXS, Goanna, Redgum – took to the stage.

David Craig was a student at the University of North Carolina when a film he believes changed the world was seen by more than 100 million Americans. The 19-year-old was not among them on the night of November 20, 1983, “distracted” as he was by life in his dorm at Chapel Hill. But he would get across the movie The Day After pretty quickly. An American public anxious about the nuclear arms build-up in the 1970s was stunned by this fictional portrayal of the aftermath of a nuclear attack. Craig would spend decades – as a TV producer and later as a film theory academic – analysing the impact of what he says is the most important television film ever made.

From his home in Los Angeles, the author of Apocalypse Television: How ‘The Day After’ Helped End the Cold War, published in 2023, says this “cheaply made disaster movie” may not be great art but its influence on history is unquestioned. “It wasn’t crafted as well as it could have been, but in a way that might have worked to its benefit, because it gave it this sense of veracity,” he says. In December 1981, an opinion poll had shown that 76 per cent of Americans believed nuclear war was “likely” within a few years, up from 57 per cent six months earlier.

Craig says that by the time The Day After screened, “the vast majority of Americans, and in fact the vast majority of humans, had come to assume we would be witnessing nuclear destruction within five years. No one saw this favourably, but what they couldn’t imagine was an alternative way of stopping it. We’d never witnessed technology reversed or regulated or governed until that point in time, so it was beyond most people’s imagination to think we could put the genie back in the bottle.”

Craig, now 60 and an associate professor at the University of Southern California, says Ronald Reagan – who’d been sworn in as president in January 1981 – was the “one person who actually believed that it was possible”. He argues the attention focused on the making and screening of The Day After helped to convince Reagan that he needed to find a way through the Cold War buildup. Historians refer to “the Reagan reversal” when the president later began seeking a rapprochement with the Kremlin.

This era was also subject to another powerful cultural influence – the cable channel MTV, launched in 1981, which created a 24/7 home for (mainly European) music videos that often featured mushroom clouds and other motifs of nuclear war. In a 2021 essay in The Atlantic, national security expert Tom Nichols writes about the difficulties of explaining the fears of the Cold War to a new generation of students. They are more or less unmoved by On the Beach, or The Day After, seeing them as artefacts – but it’s a different matter with 1980s MTV content.

“When I show them videos from the age of glitter and spandex that are filled with images of nuclear destruction, they finally grasp how much the threat of instant and final war was woven into the daily life of young Americans who thought they were turning on the television just to tune out the world,” Nichols writes. “In fact, messages about nuclear weapons, nuclear war and the end of humanity, by some counts, appeared almost hourly on MTV, making nuclear destruction second only to sex as the most ubiquitous video theme flooding the eyes of America’s youth in the 1980s … The Cold War imagery on MTV did not produce anti-nuclear revolt in the streets, but it infused an underlying nuclear anxiety into the popular culture across multiple generations.”

For Australians, this anxiety was augmented by a unique trajectory – our history of nuclear testing. As historian Dr Elizabeth Tynan points out in her 2016 book Atomic Thunder: The Maralinga Story, then prime minister Robert Menzies may have “blithely agreed” without consultation in 1952 to a telegrammed request from Britain to run the atomic tests, but within a few years public disquiet grew as “ban the bomb” gained momentum in Britain and here.

Operation Hurricane, the initial detonation in the Montebello Islands in 1952, was followed by two more (Operation Totem) at Emu Field in 1953; all three were shrouded in secrecy. There was more public awareness – and concern – about the two tests that followed in the Montebello Islands in 1956, as part of Operation Mosaic; the second test, named G2, was the biggest bomb ever detonated in Australia, although its true nuclear yield (98 kilotons, equivalent to 98,000 tons of TNT) was concealed for 30 years.

The federal government was becoming more insistent about safety measures, however, and in 1955 it set up the Atomic Weapons Tests Safety Committee as a signal it wanted to be more involved in the conduct of the British tests. The Australian public were kept in the dark about certain key things, though. “Australians were being encouraged to be patriotic,” says Tynan, who is writing a new book on the Montebello tests. “Little did they know that Australia was way down the list of places where Britain wanted to test.”

The Americans had already fuelled Australian angst in early 1954 when a Japanese fishing boat was contaminated by fallout from the Castle Bravo thermonuclear weapon test at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands; the crew of 23 suffered severe radiation sickness and one man died. Then, starting in 1956, Maralinga came online; the remote site in the Great Victoria Desert meant there was little or no media coverage of the impact of nuclear tests on Indigenous Australians or on the British and Australian servicemen involved. But bipartisan political support for the program evaporated when, in June 1956, the ALP Caucus (then in opposition) voted to ban the tests.

“There was a change of mood, and that mood was changing right around the world,” says Tynan. “You see the rise of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, and the Pugwash Conferences of scientists and other intellectuals opposed to nuclear proliferation.

“By now the Australian government was a bit fed up with the British because it started to become apparent Britain had misled Australia in some aspects of the tests. As well, the Brits didn’t need us as much because [by the late ’50s] they had got back into bed with the Americans, who had excluded them for 12 years. So all the Pacific tests, the hydrogen bomb tests, were dead ends because the British ended up just purchasing American technology.”

South Australia paid a heavy price: the major “mushroom cloud” explosions by the British ended in 1957, but radiological experiments, which caused extreme plutonium contamination, continued at Maralinga until 1963. The fallout still resonates.

Dr Paul Brown, honorary associate professor in the Environment and Society Group at UNSW, says: “If you work with First Nations communities in South Australia, or in fact pretty much any community in South Australia, you’ll still get perhaps the country’s biggest negative response to all things nuclear.”

All of this served to closely link the perils of nuclear weapons and nuclear power generation in the public consciousness. The memory of Maralinga has been amplified by the recent, failed attempt to build the nation’s first radioactive waste storage facility in SA.

The federal government continued to back nuclear, and in 1958, when opening the Lucas Heights reactor (which produces radioisotopes for medical/industrial applications and scientific research) in Sydney’s southern suburbs, prime minister Robert Menzies called it “historic” not just for Australia but for the world.

But Australia’s nuclear momentum would come to a halt. A 1969 plan to build Australia’s first nuclear power station at Jervis Bay in NSW was abandoned by Billy McMahon, who pulled the plug in 1971 amid a debate over cost and a wave of protestsled by left-wing unions.

It was a crucial juncture. Countries including France, Germany, the US and Britain were constructing nuclear power plants, even as Australia’s plan was being shelved. The election of the Whitlam Government in 1972 increased the pushback as Labor MPs, including Tom Uren, argued the Japanese bombings were a crime against humanity.

In this climate of intense backlash, journalists like Brian Toohey and Bob Milliken and science writer Ian Anderson investigated the crudely managed British tests. Their revelations about plutonium contamination at Maralinga and other safety breaches contributed to the pressure that led to the royal commission into British nuclear tests in 1984–1985 chaired by “Diamond” Jim McClelland, and in the 1990s to a notorious “final” cleanup of the site. Punctuating those events were the Cold War-era reactor accidents at Three Mile Island in 1979 and Chernobyl in 1986.

When Australia’s nuclear ban was introduced via a Greens amendment in the Senate in December 1998, there was less than 10 minutes of debate on the matter. The Howard Government at the time was seeking legislative support to build a new nuclear research reactor at Lucas Heights. A deal was done. The 1998 ban – along with other legislation – ensures Australia is an outlier, with at least 30 OECD countries using nuclear to generate electricity. They include Canada, the UK, Germany, Switzerland, Belgium, the Netherlands, Sweden, Finland, Spain, South Korea, Japan and France (where 70 per cent of the nation’s power is nuclear). And of course, we are not among the nine nations with nuclear weapons, although we have pledged to secure nuclear-powered submarines via the AUKUS agreement.

Although uranium mining is banned in several states it is permitted in the Northern Territory, South Australia and Western Australia, with Australia among the world’s largest exporters of uranium (with strict regulations and agreements that the mineral exports be used for peaceful purposes only), including to China. When, in 2006, Howard called for a debate over nuclear power to cut greenhouse emissions, then Opposition environment spokesman Anthony Albanese went on the attack. In a foreshadowing of the 2025 election campaign, Albanese told reporters that “John Howard’s nuclear fantasy is Australia’s nightmare”.

But where do Australian attitudes stand on nuclear energy today? A Lowy Institute poll last year found six in 10 Australians were “somewhat” or “strongly” in support of nuclear power to generate electricity, compared to 2011 when more than six in 10 held the opposite view. Polling group DemosAu has been testing people’s views on nuclear since last year – with the option to choose a “neutral” stance. (March polling by the group showed 37 per cent agree with nuclear power, 33 per cent disagree and 30 per cent are “neutral”). DemosAu’s head of research, George Hasanakos, says the relatively high neutral figure makes it hard to describe nuclear as “polarising” the community.

The Albanese Government has challenged the Coalition’s support for nuclear power – albeit largely on economic rather than safety grounds. The debate today focuses on the question of cost, the timelines and the practicality of delivering nuclear energy. But as the world heads toward the 80th anniversary in July of the world’s first nuclear test, Trinity, in the New Mexico desert, nuclear energy is being repositioned as the saviour of the planet, with younger generations who don’t automatically “duck and cover” when the subject comes up.

Newspolls from 2022 to early 2024 showed younger Australians believed the government should “consider” nuclear energy. In the February 2024 Newspoll, 55 per cent of all voters supported the idea of Australia having small modular nuclear reactors, but it was backed by 65 per cent of 18- to 34-year-olds. A breakdown of the total voters shows the spread of views, with 22 per cent strongly approving and 17 per strongly disapproving, 33 per cent somewhat in favour, 14 per cent somewhat against and 14 per cent ticking the “don’t know” box.

However, a Newspoll taken four months later in June 2024 showed support wavering as the party-political divide on energy policy widened. The Coalition has pledged to introduce nuclear power by 2035, proposing seven sites for nuclear stations in June – a plan that the Albanese Government instantly branded a “fantasy” and “economic madness”. The June Newspoll taken soon after recorded 42 per cent in support and 45 per cent disapproving, with 13 per cent sitting on the fence.

Which brings us to today’s pop culture Zeitgeist – encapsulated by the 2023 blockbuster film Oppenheimer. Director Christopher Nolan depicts theoretical physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer, the so-called “father of the bomb”, having mixed feelings about his 1945 creation. Of course, at that time nuclear research had high acceptance levels among Americans who were fearful about the Soviets’ capability and intentions. Amid the horrors of World War II, the argument that dropping the atomic bombs on Japan was the least worst way to end the war was easily made.

Nolan chose not to make his depiction of the horrors of Hiroshima overt. In an interview with film industry bible Variety he said: “The film is an honest attempt to express my feelings about it.” Those feelings were, like Oppenheimer’s, mixed. “My research and my engagement with this story tell me that anyone claiming a simple answer is in denial of a lot of the facts,” Nolan said. “Obviously, it would be much better for the world if it hadn’t happened. But so much of the attitude toward the bombing depends on the situation of the individual answering the question. When you speak to people whose relatives were fighting in the Pacific, you get one answer. When you look at the devastating impact in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, you get another.”

Ultimately, Nolan’s film has as much to say about the machinations of US domestic politics as it does about the bomb. At its heart it is a biopic of Oppenheimer, the conflicted physicist played to acclaim by Cillian Murphy. The movie demonstrates several things, not least that audiences have such an enduring fascination with the Cold War that a story about one of its scientists who died in 1967 grossed $US958 million at the box office and won seven Oscars, including last year’s Best Picture.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout