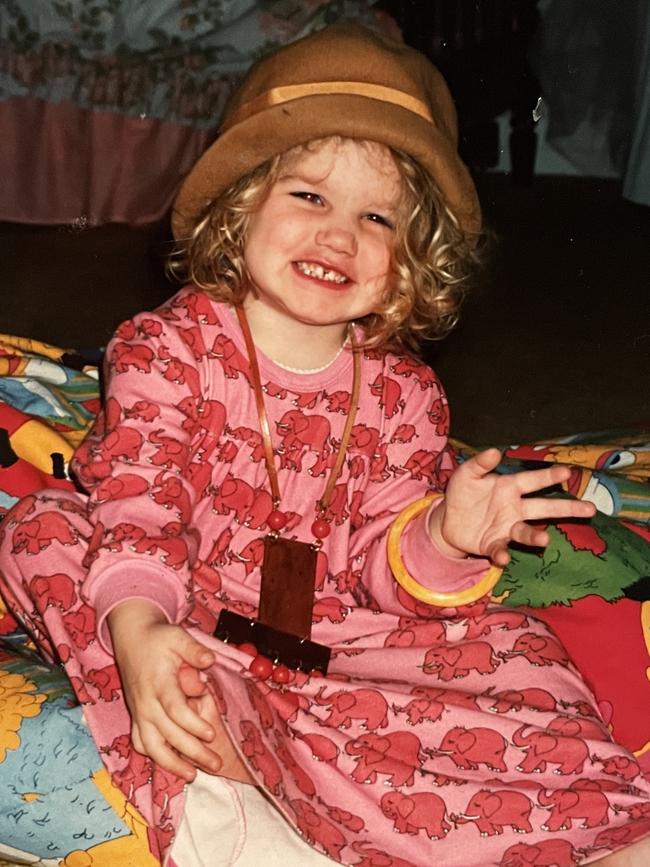

How cystic fibrosis miracle drug Trikafta changed Emily Naismith’s life

Emily Naismith had been wracked by the symptoms of cystic fibrosis since childhood. But then she took two orange pills that changed everything.

I don’t really know who I am anymore. I know … does anyone ever really know who they are? Yeah, I took philosophy classes at university but that’s not what I’m trying to say. I’m talking about when your body instantly changes the way it works at a cellular level, and the effect that has on your identity and who the hell you think you are. I want to tell you about what happens when you wake up one day, take a couple of tablets and your body, life and identity completely changes (for the better… I think, anyway).

It began in May last year. I picked up a delivery from the post office, unwrapped it and popped two orange pills down my throat (chased by a spoonful of peanut butter, because it needs about 10g of fat to be properly absorbed). They’re what’s known as “gene modulators”. This specific one, Trikafta, is designed to correct a faulty protein in my cells caused by the gene mutation that causes Cystic Fibrosis (CF). It’s a life-limiting genetic disorder caused by a malfunction in the exocrine system – responsible for producing saliva, sweat, tears and mucus.

I’ve had CF my whole life. It’s a chronic illness that affects my lungs, digestive system and other parts of my body, making me cough almost constantly; get annoying, persistent lung infections; swallow tablets whenever I eat to help digest food, etc etc.

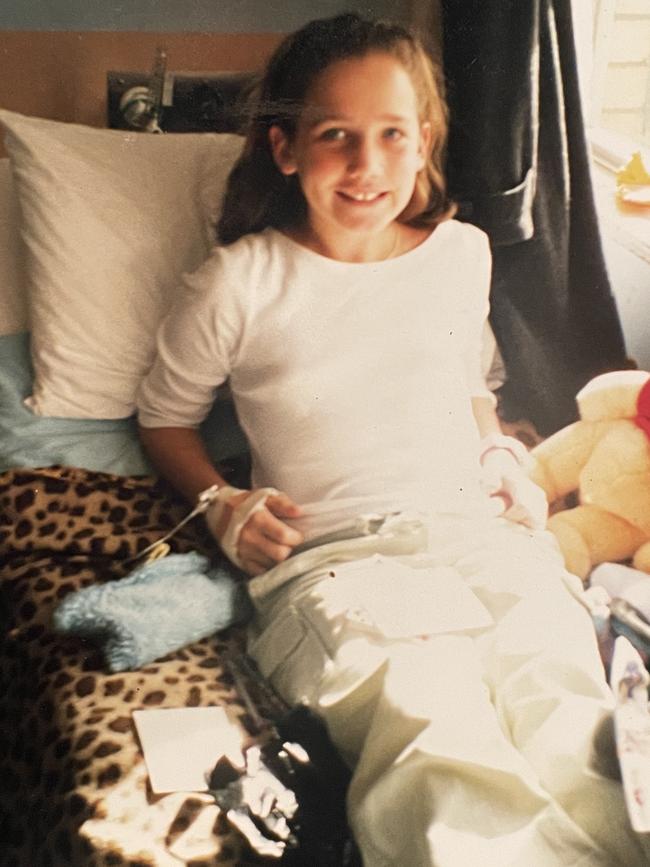

The lung stuff is the hardest part of having CF for me. My lung function has been in progressive decline since I was a child. Once it slipped to about 35 per cent when I had a partially collapsed lung, but usually it’s around 69 per cent (100 per cent is the number predicted for my age and gender). I spent chunks of my younger and teenage years in hospital wards having “tune-ups” for my lungs (a course of intravenous antibiotics) when I caught a bad cold. (Don’t feel sorry for me, some of my most fun memories take place in hospital, including line dancing with the nurses while connected to IV poles and winning McDonald’s prizes because I was at the in-hospital “restaurant” so much.) I typically can’t talk in the morning without chugging on two different puffers and my cough wakes me up at night. I’m the person usually mistaken for a chain smoker despite never sucking on a dart, for obvious reasons.

But back to the gene modulator. I had been waiting years for Trikafta to be added to the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme because at $250,000 a year for the pleasure of throwing it down your gullet twice daily, without government support it’s a little (OK, massively) out of my price range. Not everyone with CF can access the drug either, due to the different genetic mutations that cause the disorder. I was excited to start this medication, touted as a “miracle drug”, to see if it made me feel any different.

It did, almost instantly. Half an hour after the first dose my chest felt like I had wound down the windows of my stuffy car for the first time while hooning down the freeway – there was wind whipping in from all angles, filling up parts of my lungs I didn’t even know existed. I inhaled and it felt cold and exciting.

Then I started choking. This is the gross part – it has to get worse before it gets better, unfortunately (skip this part if you’re squeamish). In what is colloquially known as “the purge”, all the sticky mucus that had been hanging out in my lungs for years became easy to cough up. My cough changed from sounding like a lonesome dog to an impaled hippo. For about five days I didn’t stop hacking up phlegm. I have never felt so disgusting, but in a strange way it was also oddly satisfying (in the same way that cleaning mould from bathroom tiles is). Good riddance.

Once the purge was over, I was keen to put my newly functioning genes to work. A few weeks prior, I’d been reminded (having conveniently forgotten for eight years) that I also have osteoporosis, a side-effect of CF, and need to do weight-bearing exercise a few times a week to prevent my bones from weakening even more. So despite exercise not being part of my identity at all, I’d been going on what I termed “baby runs” where I run for a few minutes then walk while recovering (coughing, thinking I’m going to die, etc).

It felt incredibly weird on my first baby run post-Trikafta because my body could just… work. Like, I could run without wanting to crumble to a husk. I took 10 strides and started beaming like one of those freaks who smiles while they’re jogging. It was uncontrollable! More than smiling, I felt like dancing, DANCING while I was running. It was unhinged behaviour.

Previously, I could never understand how people could find joy in running. I was a pretty dedicated swimmer in my primary school years and I thought, much like a dugong, my body was just built for water; when I get on the land I just flail about, flapping my limbs in protest. I stopped swimming at around 13 and chose the path of schoolwork, snacks, music and boys – exercise was for capital L “losers”.

Obviously I know it’s actually kind of important, but I still felt exercise was uncool 20 years later. Like, I’d roll my eyes if someone I knew posted a photo after their run or I’d be dismissive if my husband wanted to go for a bike ride instead of getting brunch at a cafe. Well, this is awkward, but I need to apologise because I get it now. When you set a goal, whether it’s running for two minutes non-stop or 10km non-stop, and your body largely plays along and the endorphins hit while Rihanna is pounding in your ears, it feels bloody good. My dugong flippers can find joy in running.

-

I took 10 strides and started beaming … It was unhinged behaviour.

-

This is what is so mind-bending about this gene modulator. I feel like a different person. I know it’s just correcting a malfunctioning part of my DNA, but still, it is changing the genetic code that defines who I am (in part, anyway).

Let me try to explain. I remember drawing rudimentary self-portraits of myself (like any good little eight-year-old narcissist) on the way up the National Highway from my home in Melbourne on a family holiday to the Gold Coast. I drew one picture for each year of my life (hairstyles and outfits changing as rapidly as Beyoncé in concert) all the way up to 24 years old. I didn’t really think about it that much, but I did know somewhere in my mind that I probably wouldn’t live much longer than that. I’d had friends with CF who were my age die already. I wasn’t sad, it’s just how it was.

This is how I’ve felt my whole life. I’m now more than a decade older than my final self-portrait and I’ve achieved way more than I thought I ever would – I have a beautiful son, supportive husband and successful career in writing and marketing – but I’ve always felt like everything’s going to come crashing down at some stage: the declining lung function leading to lung transplants leading to, ugh, I don’t even want to type it.

So when, in 2022, aged 35, I ran 11km non-stop and crossed the finish line after a 1.5km ocean swim, it didn’t break my body; instead it broke my brain to pieces. Who is this new gal? Where did she come from? Was she always there, just waiting for the little genetic code to be flipped so she could shine? Or was she born when I started breathing deeper? I like this new me. It’s incredible to consider what else I could try that I never thought I’d be able to. I love knowing I’ll be able to see my son grow up to be an adult. It’s glorious waking up and being able to breathe freely; I don’t even need puffers anymore! My lung function is back up to 82 per cent. I rarely cough. I feel so grateful for these positive changes (if also mildly terrified that the drug will be taken away from me due to potential side-effects), but sometimes I feel like I’ve lost my old self, and I liked her too.

A good portion of my pre-Trikafta identity was based around my cough. My friends used to tell me they knew where I was in the office or at the shops because they could hear it. I thought it was kind of endearing. I used to explain how I had CF to most new people I met so they didn’t think my cough was scary or contagious. Now that I don’t really cough, it’s like a chunk of me is missing. No one would ever know I have CF, really. And it’s complex because while I love being able to breathe (how good is breathing?) I’d always be the first to jump in and tell anyone that I don’t hate having CF. I’m kind of proud to have it. It’s made me who I am, and I like who I am. Or was…

I’m told this feeling could be “disenfranchised grief”. It’s typically when others invalidate our grief, but on this occasion it’s my own brain judging the sadness as unnecessary because it thinks I should only be happy and grateful! And obviously, I am those things! I’m basically obsessed with my new self. But at the same time I’m really conscious of never forgetting how much I endured and got through, because it’s defined who I am and how I exist in the world.

Anyway, at the moment I’m just trying to exist in space-time, playing with my new powers and trying not to forget my past. I don’t know who I am, or who I will be next year but maybe that’s OK. I do know little eight-year-old me better get her pencil sharpened because there’s quite a few more self-portraits to crank out.

Emily Naismith is a writer, co-host of food podcast Ingredipedia and branded content director at frankie magazine

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout