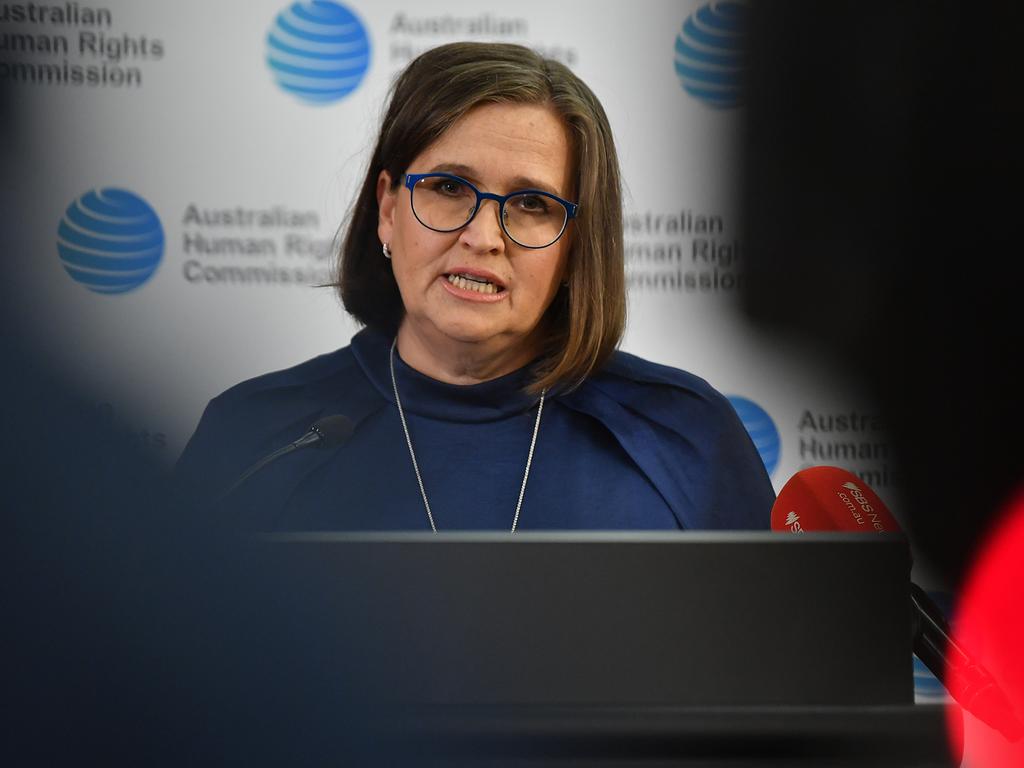

Kate Jenkins reveals her own experience of sexual harassment

Outgoing sex discrimination commissioner Kate Jenkins has revealed her own experience of sexual harassment.

Kate Jenkins wears her influence discreetly. She might be the tenacious bureaucrat who is changing Canberra, but at a busy restaurant on a Thursday night in Sydney she experiences some of the ignominies that women of a certain age understand intimately. There’s the mystery of the waiter who conscientiously attends to other diners yet repeatedly misses the nation’s sexual discrimination commissioner. And there are Jenkins’ own efforts to attract the attention of any employee, waving, smiling, gesticulating, without much luck. When she finally manages to snag a dessert menu, two and a half hours after being seated and largely ignored/forgotten/invisible, she is magnanimous. “I’m mostly pretty mild-mannered,” she says, finally submitting her order with a smile and a gracious thank you. “I actually don’t get too worked up about things.”

During her 30-year career, that trait has been an asset. As an employment lawyer for two decades and then Victoria’s Equal Opportunity and Human Rights Commissioner, Jenkins heard countless stories of workplace misbehaviour. Over the past seven years, that focus, the number of accounts and their impact, has intensified. Her soon-to-be-finished term as the nation’s seventh Sex Discrimination Commissioner has coincided with the rise of the MeToo movement and she has presided over a series of reviews revealing that sexual harassment is endemic across the nation. Despite a stream of ever depressing statistics – and having headed perhaps the nation’s most public workplace review, her 2021 inquiry into the culture at Canberra’s Parliament House – Jenkins’ equilibrium has remained. Along the way she has managed to assume such stature that her surname, in some circles, has become a byword for upstanding behaviour. “She was the ideal person at the ideal time, because of her experience and her gravitas and also her approach,” says independent federal MP Helen Haines, who lauds the goodwill and lack of intimidation that Jenkins brought to the 2021 inquiry. “She brings an optimism that we can all do better.”

In fact, Jenkins has delivered more than empathy and encouragement to the job. She has also brought a wealth of experience, some of it first-hand and very personal.

She is a perpetual fixer. Her career has spanned decades and designations, but it has also entailed a lot of mending and changing. Despite her differing roles and worlds, common themes – power imbalances, sexual harassment and sexual assault – have continually crossed her desk. “I’m still hearing the same cases,” she says of the range of workplace woes she has encountered in the decades since she started as an employment lawyer in Melbourne.

She is an affable subject, generous with her answers and prone to positivity, the latter a surprising feature given the often confronting nature of her work. Having been raised on an orchard on Melbourne’s fringe, gender inequality was something she read about more than experienced for a long time. “I had grown up with two brothers and parents who believed we were equal.” So she was outraged when, aged 11, she learned in 1979 of pilot Deborah Lawrie’s High Court battle just to be allowed to fly as a commercial pilot. At Tintern Grammar, then an all-girls’ high school, she was accustomed to seeing females achieving the best, and worst, in every subject. Years later, as she began studying arts law at Melbourne University, “I remember thinking, ‘Why do the boys get to speak more in class?’ That was the first time I had noticed.”

By the time she joined a major law firm in 1993, the finer details of the 1984 Sex Discrimination Act were still being absorbed. Young and learning on the job, she became a specialist on the legislation and its workplace implementation. She spent her days resolving other companies’ problems, helping airlines and others navigate discrimination laws, often dealing with “a mix of everyday sexism and sexual comments. I used to joke that I was always busy in January after the Christmas parties.” Like clockwork, after one bank’s annual conference she would invariably land a couple of cases.

Behind the scenes she was hearing countless disturbing anecdotes. “It was this normalisation of sexual and sexist cultures,” she says. “It was the typical older man having an affair on the side with a graduate, where the power differentials are so different. It was a Christmas party where people had too much to drink or a stay-away conference. It was diverse workplaces where comments were made, often by men.” The companies she was advising were desperate for these stories to remain private. “And I realised how much I was part of the system; I knew if this got out it would be bad for the share price. A lot of work was done to help keep things quiet.”

She observed other patterns, too. Time and again she saw the adverse consequences for complainants who raised workplace issues – Jenkins among them. As a young lawyer, “like almost every woman”, she was sexually harassed at work. Having endured “the sexual comments and stuff that we all thought we had to put up with”, she learnt that some colleagues had been joking aloud about her private life behind her back and she complained to her supervising partner. “Given I worked in this area, I felt it appropriate to remind the firm of its obligations, and I wanted the people making the comments to understand it wasn’t acceptable, even if I wasn’t there.”

She was shocked when that simple act ricocheted to her disadvantage. “It was such an awful experience and I thought, ‘I didn’t even do this’. I was having to explain what I had done, and it pitted me against my co-workers and it was so long and it was so draining,” she says now of the process that ended with her workmates being reminded to behave appropriately. “I don’t think that helped my career. I think some of my peers were suspicious of me. And I remember thinking, I wouldn’t do this again.”

Decades on, and despite having produced eight independent reviews into cultures ranging from universities to gymnastics, some things have not changed. “It’s still not good for people to raise issues,” Jenkins laments of the often poor outcomes for those who speak up. “[Too often] there’s almost no benefits.” Over the last five years only 18 per cent of those who were sexually harassed at work even lodged a formal complaint. “They say they fear they won’t be believed,” says Jenkins. “They fear that nothing will be done about it. They fear that it will affect their careers.”

What, then, would be the outcome when Jenkins probed what she describes as “to some degree … the most important workplace” – the nation’s Parliament House?

Jenkins had been the Sex Discrimination Commissioner for just 18 months when the tone of her work changed irrevocably. She had been appointed by then attorney-general George Brandis in April 2016, after 20 years as a lawyer and three years as Victoria’s Equal Opportunity and Human Rights Commissioner, and was passionate about securing gender equality. By October 2017, as she returned to her family – husband Ken Lark, two children and three stepchildren – from an overseas trip, she switched her phone on to be inundated with messages about a story breaking in The New York Times. The powerful Hollywood film producer Harvey Weinstein was alleged to have sexually harassed, assaulted or raped multiple women over several decades.

–

As a young lawyer she complained when, “like almost every woman” she was sexually harassed at work. “It was such an awful experience”

–

The themes behind much of Jenkins’ life’s work were suddenly headlines globally and as more Weinstein revelations emerged, in Australia the reluctant acceptance that sexual harassment was an inevitable part of employment seemed to shift. As Jenkins would later declare when she released the fourth national survey on sexual harassment in Australian workplaces: “The Australian public has rightly demanded to know more about the pervasiveness and impact of workplace sexual harassment and to see concerted action taken to prevent this behaviour occurring.”

The workplace sexual harassment survey had been conducted roughly every four years since 2003. After the Weinstein reports began to emerge, Jenkins secured extra funding from the Department of Social Services to conduct a larger survey that would hone in on specific industries. Those findings painted a detailed, dismal picture. “I expect the results I share today might shock some of you, particularly those of you who subscribe to that generational theory of change,” Jenkins told the National Press Club in 2018 as she detailed the responses of 10,000 participants, five times more than in past surveys.

A staggering one in three Australian workers, it emerged, had been sexually harassed at work in the previous five years. The vast majority of harassers were men, and the conduct continued with impunity. Only one in five people harassed actually complained, and among those who did, half maintained that nothing had changed as a result. With 85 per cent of women and 57 per cent of men having been sexually harassed at least once, “our survey findings,” Jenkins told her Canberra audience, “indicate that sexual harassment is endemic in Australian society, across all areas of daily life”.

The extent was not enough to prompt immediate change, however. It would be two more years until Jenkins completed yet another review – which she revealed as the world’s first national inquiry into workplace sexual harassment – examining the systemic issues behind the prevalence of sexual harassment at work. With the results of the 2018 survey forming its basis, this inquiry probed not just the nature and prevalence of sexual harassment at work but also the drivers the behind it. Although she had heard so much already, Jenkins was not immune to what came next. “I have been devastated by the experiences of sexual harassment within workplaces I have heard about through this inquiry, the harms suffered by victims and the cost to the economy,” she declared as she unveiled the findings in her Respect@Work report in 2020. “As Australia’s Sex Discrimination Commissioner, I deliver this report with a sense of urgency and hope.”

After years of listening to accounts, she was struck by the long tail of many. “We were hearing from people who had been harassed 15, 20 years ago and they either raised it and their work was ruined or they left the industry,” she says now. One woman who had been harassed signed a confidential settlement which meant that she could never discuss her experience, even as she failed to ever earn as much money again, and even as she continued to read about the ascension of the alleged perpetrator, who went on to become a global partner.

“Workplace sexual harassment is prevalent and pervasive: it occurs in every industry, in every location and at every level, in Australian workplaces. Australians, across the country, are suffering the financial, social, emotional, physical and psychological harm associated with sexual harassment. This is particularly so for women,” Jenkins declared at the start of the Respect@Work report, which was tabled in Federal Parliament in March 2020. Her report’s 55 recommendations sought to form a new evidence-based and victim-focused model “to create safe, gender-equal and inclusive workplaces” and to comprehensively change how the nation responds to and prevents sexual harassment.

Australia, which had once led the global assault on sexual harassment through the ratification of international conventions and the enactment of legislation dating back to the 1970s, said Jenkins, “wants change.” She had no idea how prescient those words would be.

In early 2021, Liberal party staffer Brittany Higgins alleged in media reports that she had been raped in a ministerial office inside Parliament House in Canberra. By March, with the story national news, Jenkins was asked by the Morrison government, with the support of the federal opposition and crossbench, to review federal parliamentary workplaces.

Over the following seven months, she and a staff of about 20 ploughed through the responses, from surveys, interviews, focus groups and written submissions, of more than 1700 people. Their work, Jenkins knew, would be widely scrutinised. As she declared when her report was released in November 2021: “The Commonwealth Parliament sits at the heart of Australia’s representative democracy. As one of the country’s most prominent workplaces, it should serve as a model for others and be something Australians look to with pride.” Instead, she found a toxic environment “largely driven by power imbalances, gender inequality and exclusion and a lack of accountability. Such experiences leave a trail of devastation for individuals and their teams and undermine the performance of our Parliament to the nation‘s detriment.”

As the daily workplace of 4000 people, Parliament House lacked, among other things, a universal code of conduct, a sufficient degree of accountability (“people who engaged in misconduct were often rewarded for, or in spite of, their behaviour), even a clear hierarchy, plus “the particular difficulty of sanctioning parliamentarians who engaged in misconduct, because they do not have an ‘employer’.” There was no HR support and there was a lack of diversity. As Jenkins says now: “It was missing all the structures to make it a productive, positive workplace.” More than half of those working in federal parliamentary workplaces had been bullied, sexually harassed or subjected to attempted sexual assault there, including one respondent who provided this indelible anecdote: “[T]he MP sitting beside me leaned over. Also thinking he wanted to tell me something, I leaned in. He grabbed me and stuck his tongue down my throat. The others all laughed. It was revolting and humiliating.”

Amid complaints about a leadership deficit (“many discussed the way in which leaders themselves were responsible for bullying, sexual harassment and sexual assault, and also their inadequate responses to the misconduct of others”) and a paucity of consequences when complaints were made, Jenkins observed some familiar patterns. Most people did not report incidents, believing they were not serious enough or that they would be deemed to be overreacting. And for young staffers new to politics, she says now, “there was very much a sense of ‘you have to put up with abuse and sexist and sexual remarks … or leave’.”

Would anything ever improve?

–

More than half of those working in federal parliamentary workplaces had been bullied, sexually harassed or subjected to attempted sexual assault

–

After decades of work and multiple reviews, Jenkins understands that change usually occurs as a result of scandal. She sees Canberra’s response to her work as a litmus test for the rest of us. “To some degree they are the most important workplace. So if they couldn’t do it, then we can’t expect any other workplace to be safe and respectful.”

While the government tabled her report in parliament immediately, almost three months lapsed before it was addressed in its truest context. In the first minutes of the first sitting day of 2022, Federal Parliament addressed Jenkins’ findings, acknowledging “the unacceptable history of workplace bullying, sexual harassment and sexual assault in Commonwealth parliamentary workplaces,” house speaker Andrew Wallace told the chamber, and party leaders confirmed they would endorse the report. “We today declare our personal and collective commitment to make the changes required. We will aspire, as we should, to set the standard for our nation,” Wallace said.

That afternoon, a succession of MPs rose to acknowledge Jenkins’ work and her findings. “Over many decades, an ecosystem, a culture, was perpetuated where bullying, abuse, harassment and, in some cases, even violence became normalised,” said then prime minister Scott Morrison as he apologised to those who had been assaulted and harassed in a workplace that “should have been a place of safety and contribution (that) turned out to be a nightmare.”

“This very institution that failed you is at last acknowledging your hurt,” said then opposition leader Anthony Albanese. “Most importantly, we are sorry … The Jenkins report, with its piercing honesty about the treatment of women and men both, has exposed a damaged culture, and no word any of us says in here is worth a thing if it does not lead to action.”

As Jenkins watched parliament live on her iPad (Covid restrictions kept most observers away), she was deeply moved. Her report had recommended an acknowledgment of historical wrongs, rather than an apology. “If someone tells you to apologise, that’s not a genuine apology,” she says now. Yet here were politicians lining up to do just that, and promising to enable change. Jenkins became emotional as she watched both houses endorse all she had recommended. “It was a mixture of joy that there was this recognition, sadness that all these people had had these experiences.” And a touch of personal pride, after working for so long, in some ways, to this moment. As she says: “It [the review] was the piece of work that brought together everything I have learned over my entire career.”

Today, almost 18 months after Jenkins’ Parliament House review was released, and to the amazement of many, the shoots of change have indeed emerged in the national capital. Codes of conduct have been introduced for all MPs and staff. An Office of Parliamentarian Staffing and Culture is being established to provide workers HR support, among several of Jenkins’ 28 recommendations that have already been introduced.

But beyond those directives, people seem to be behaving differently. “There’s an awareness that wasn’t there before,” says Helen Haines, who in recent months has observed subtle changes at her Canberra workplace. “I get a sense that people are looking out for staff members. People are thinking about what effect might this have on a staff member in my office or in someone else’s office.”

From her desk at Federal Parliament, Liberal MP Bridget Archer agrees. “If you work in here, it’s a tangible vibe. It does feel different, and I certainly notice that people talk [differently], and they reflect on it [the report]. I get a sense that people are being very thoughtful about their behaviour and interactions.” Only hours before, Archer had heard Jenkins’ name mentioned after a colleague made a joke that might have been deemed questionable. “It was almost calling someone out,” she says. “As if to say no, that’s not really appropriate … That’s what it [Jenkins’ work] has created.” In the 47th Parliament of Australia, Labor’s Senate president Sue Lines often invokes the name of the nation’s outgoing sex discrimination commissioner. “When question time is rowdy or there’s poor behaviour I do remind people of Jenkins, particularly that we have signed on to behave respectfully.”

There are other changes. Some MPs are hosting work events in their Canberra homes rather than in public. Female journalists report a drinking culture that has become more subdued, and a greater willingness to call out others for inappropriate behaviour. “You can almost see the words ‘respect at work’ flash across their eyes,” says one young reporter.

“What Kate’s work has done is taken off the blinkers of this blokey cultural blindness that was there before,” says Haines. “She was able to encourage people to be their best selves and we have responded to that.” She is confident that the newly emerging sense of civility will be permanent, and not just because there are now more female MPs, including multiple crossbenchers who campaigned on gender issues. “I just don’t think anyone here would accept going backwards. I honestly can’t see a world where this Parliament House would accept that the blokiness, the old boys’ club could ever be reignited in a way that would trample on the good work of Kate Jenkins’ report.”

The night ends much as it began. “The thing about Parliament is it shows you can get change quickly,” says Jenkins, still magnanimous, polite and seemingly invisible as yet more wait staff are flagged down for the bill. “There’s no rule that says you can’t have a drink with your colleagues, that you can’t have fun, that you can’t be funny and have a laugh … I am just saying ‘treat all people well’.”

After all the reviews and anecdotes and inertia, that seems to be the essence of her simple ethos. “You’ve just got to always be a decent human being,” she says as she heads towards an unknown future, happy to wait for whatever comes when her term ends in April. “It’s not that hard.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout