Happy, safe ... and 3500km from home: Tennant Creek kids find sanctuary in Hobart

Amanda Ducker has made a promise. She will raise these two Indigenous children far away from the chaos of their native Tennant Creek — and the government can stay out of it.

In a house on a hill a family is sitting down to dinner. There are platters of roast chicken and veggies on the old wooden table that dominates the oversized living room, with its fired-up wood-burning stove at one end and a picture window overlooking chilly Hobart at the other.

“I don’t think people understand our mixed family,” says Amanda Ducker as she presides over the mid-winter feast, carving up a vegetable pie and passing around a large bowl of salad to a gathering groaning with those she loves. Around this table, host to generations, sit two of her three young adult daughters, her partner, and the two lively primary school cousins for whom Amanda, without any biological connection, has become fondly known as “second mother”.

With their blood relatives thousands of kilometres away, these 11-year-olds are being raised in a far corner of Australia where nothing – climate, culture, kin – is quite as their indigenous families had once imagined. They are here without any official legal endorsement, but with the blessings of their elders, to be raised by a non-indigenous woman who, despite an abundance of devotion, concedes that “it’s only half a life in Hobart for these kids”.

So, with the help of an ageing LandCruiser parked on the hill outside, Amanda and the two cousins are about to embark on a journey. The old car, beaten and beloved, with a bull bar at the front and a few bunks at the back, is about to become a conduit between two spheres of Australia, the conveyor of a cross-country trek that Amanda, and others in the inner orbit of these cousins, hope might yet become a new way of raising some of the nation’s most disadvantaged children.The route from Hobart to Tennant Creek is 3500km, from island to desert, via a long swathe of the continent, and with a ferry ride across Bass Strait. When Amanda last navigated it in 2021, only weeks after being made redundant as a journalist at The Mercury newspaper in Hobart, the trip became unimaginably momentous. But the genesis of the journey that links her family with one at the other extremity of Australia in fact began decades earlier.

“This year, end of June, I’ll be visiting a new school.” When Latenzia Grant, aged 12, speaks to the camera, she is shy at first, but then she throws in an impish “yeh!” and out comes her breakaway smile. It is 2003 and Tenny, as she is mostly known, is one of 15 students at Warrego Primary School, an educational speck on the edge of the Tanami desert.

Warrego was once a mining town of 3000, but when this footage is filmed for the documentary Bush School, the mine has closed and Warrego is all but emptied. The arrival of educator Colin Baker and his wife Sandra reinvigorates the tiny community, and soon a handful of children are enrolled at the remote NT school, and learning to swim and horse-ride.

Tenny dreams of becoming a teacher. She is not the class’s top student but she is a stand-out rider, and through the Bakers’ links to the New England Girls School she moves across the continent to Armidale. Arriving with a horse called Silverado from the Bakers, she becomes a high school boarder in NSW on a riding scholarship.

Half a continent away, she has the blessing of her parents, who have already sent her to Warrego from their home in Tennant Creek. “They wanted Latenzia out of there,” says Sandra Baker, referring to the social ills, including substance abuse and poor school retention rates, besetting the NT town. “They wanted her to get a good education. They didn’t mind if she came back to help the community, but she would have to do it from a Western perspective.”

Cold, regional and largely Anglo, Armidale is another world for Tenny, but she adapts well. Then comes her first mid-term break, when most students travel home or visit friends, but she does not. It is 2004 and Meg Ducker, one of the school’s house mothers, is worried that a child is alone. “She rang me up,” says Meg’s partner Peter Vyner, “and said, ‘This little girl has got nowhere else to go’ and I said, ‘Just bring her home’.”

And so begins Tenny’s enduring relationship with the Ducker family. She stays with the couple for multiple weekends, and then each school holiday, except for Christmas when she is able to return to Tennant Creek. “She just fitted it,” says Vyner. “Like a daughter really.”

Tenny is quickly absorbed into her New England family. Meg’s daughter Amanda lives two hours away with her toddlers in Nundle and also forms a bond with the teenager from the Territory. “It just seemed as if she entered our family that weekend and never left.” Tenny eventually moves in with the couple full-time and, apart from end-of-year trips home to Tennant Creek, remains with them for the rest of her education.

When she is in Year 9 she joins her Armidale family in Sydney for a break. Bush School has just screened on TV and she giggles when she is noticed in public. But the glee of that trip is soon erased. “She was ringing family to tell them that she’d been sailing under the Sydney Harbour Bridge,” says Amanda, “when she was told there had been an accident.” Tenny’s father is dead.

She races home. Sorry business takes time and the Duckers wonder if she will return to her southern life. She does eventually, and completes Year 10. But then in 2008, halfway through Year 11, she leaves New England for good. “The longing set in and she just had to go,” says Amanda. After years away, the sum total of Tenny’s life is still trumped by the lure of home.

Contact with her southern family stalls, despite the efforts of its matriarchs, who are stymied by changed phone numbers and a suddenly inaccessible Tenny. “She kept both worlds separate. So if she was having a struggle up there she would be very reluctant to tell us,” says Amanda. “Mum tried. She said she would never change her phone number, she was just waiting for the time Tenny rang. And she did ring a few times over those years.”

And then suddenly in 2012, Tenny, now 20, calls – and reveals that she has become a mother. Her daughter Naida is only months old. In December, she and her baby travel for Christmas to Hobart, where the Duckers now live. They stay for four years.

“We were just overjoyed to see her and this marvellous little baby,” says Amanda, beaming. “It was thrilling and beautiful to have her back and to be able to help her raise Naida.”

Tenny is a fun and affectionate mother to her exuberant, spirited little girl, and they settle into a small flat in inner Hobart. Life back at home in Tennant Creek, Tenny suddenly reveals, is chaotic. “She wasn’t with the father of the child. She felt she was making some bad choices and she wanted to get the hell out before she made any more. She really wanted to focus on being a good mother, and she was,” Amanda says. “She felt like she was at risk of the influences around her. She has beautiful family members, but everyone is at risk of being sucked into the black hole of what life becomes like with profound generational displacement.”

In cool Hobart Tenny joins the crowd at kids’ soccer lessons on the weekends and enjoys family dinners in Amanda’s cavernous front room on Friday nights. She attends TAFE to finish her schooling, and is selected for an indigenous youth program, a prestigious pick that culminates with her walking the Kokoda Track.

But the sense of her other world never quite disappears; most nights she spends hours on the phone with her sisters and cousins in the NT. With the leadership course over, she seems to lose focus. And there is her ongoing concern for the wellbeing of her widowed mother in Tennant Creek. “She lost momentum,” says Amanda. “There was a lot of loss happening at home. She was just missing everything up there.”

In January 2017, Tenny loads five-year-old Naida into an old van, and they resume life in Tennant Creek. She finds work as an administrative assistant for the Northern Australian Aboriginal Justice Agency. Sandra Baker calls and is encouraged by the life Tenny is forging. “She was handling herself quite well. We were talking about what she might do next.”

But the silence that again ensues when her Tasmanian family try to reach her is foreboding. “I was scared she would get sucked into the cycle of drinking and despair,” says Amanda. “No news is not good news with Tenny; when there’s trouble you go to ground.” After much coaxing, Tenny eventually reveals that she is drinking heavily. “When we realised that she was going off the rails, when we realised how bad it was, I asked her if she wanted to send Naida down to me for a while, while she got herself sorted.”

The seven-year-old girl she meets in Hobart in July 2019 shocks her. “It felt like receiving a war child.” Naida is thin, has behavioural problems, little literacy and is on high alert. When Tenny arrives a few months later, she, too, is noticeably different. “For the first time I saw her drinking,” says Amanda. “She was drinking a lot. And I remember Mum saying, ‘That’ll be it then; the grog’s got her’.”

A few days after Christmas 2019, in the Hobart living room that has been the focus of so much of the family’s life, Tenny and Amanda settle into two armchairs, and their worlds, already linked, become irrevocably intertwined. Tenny is just 28, and her future, in her own eyes, is grim. “She said: ‘Manda, I will take every grey hair for you, I will take every one of your pains, I will take every one of your wrinkles, if you will raise Naida for me. I’ve lost control’.” The fears that her parents had held during her childhood, when they sent her away from town, appear to have become her adult reality. Days later, as 2020 begins, Tenny leaves for Tennant Creek alone. Then the country locks down because of the emerging Covid pandemic.

For the next year and a half, Amanda continues to raise Naida without any government oversight, just a statutory declaration from Tenny’s employer delineating the two women’s responsibilities and areas of guardianship.

When she can, Tenny sends money south. “Obviously Latenzia [Tenny] was the person to make any big decision. But I was in charge of all of Naida’s day-to-day decisions including medical and education,” says Amanda, who uses the statutory declaration to admit Naida into a local school. When the declaration lapses, the two mothers, who are in regular contact about the daughter they are raising, continue as though it still stands.

“I saw this as a private family matter,” Amanda says of her resistance to inserting officialdom into an already emotional equation. “Neither of us wanted anyone meddling in our affairs. For God’s sake, there has been enough control over Aboriginal people.”

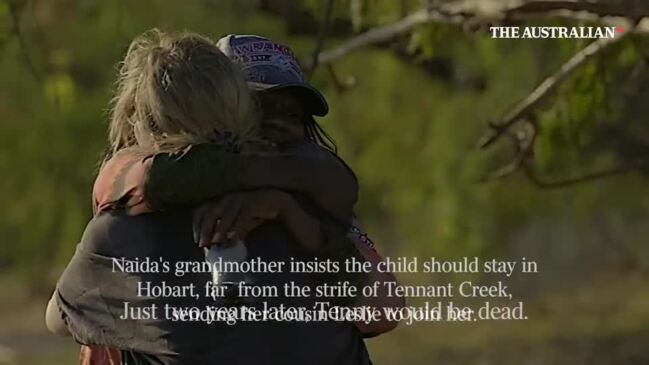

As Covid restrictions ease, in mid 2021 Amanda and Naida set off for Tennant Creek in an old LandCruiser. Days later, deep in the NT, they meet Tenny near Barkly Homestead about two hours’ drive from town. “She was waiting by the side of the road with her arms above her head and I just had this great sense of relief: mother and daughter are reunited.” The following day, they drive to Tennant Creek. They plan to stay there for close to a week before heading to Darwin for a holiday, where they will discuss Naida’s future – although Tenny has already confided to her aunt Josephine Grant that, with her new partner in jail, she plans to move back to Tasmania.

In Tennant Creek Tenny is upbeat, and invariably surrounded by some of the many children in her extended clan whom she adores. She organises visits to family and on the fifth day they attend a local football match. When it ends, Amanda returns to her LandCruiser with plans to meet at a concert that night.

At the local campground it is happy hour. A guitarist serenades guests, singing “every day is Australia Day” as Amanda takes out her journal. I’m realising I am not going to have Naida that much longer if Tenny stays in this role of sobriety, she writes. I would like Naida to come home if she can. I want her to be with her family. But more than that I want her to be safe.

When Tenny messages later that evening to pull out of the concert, Amanda is unperturbed, and remains so even when she calls Tenny the following morning and there is no answer. Then Tenny’s younger sibling Lavina Grant suddenly arrives at the campground early on Sunday, distressed. “She said: ‘We can’t find sister.’”

After the football match, Tenny begins drinking. She is joined by a friend and by a visiting footballer from Borroloola who has been part of the afternoon’s match. Dwight Raggett, whom Tenny has not previously met, is 21 and although he has never held a driver’s licence he soon takes control of her prized Kia station wagon. Over the following nine hours he drinks and he drives her car, Tenny also drinking but becoming increasingly irritated that Raggett will not hand over her keys. Around 3am, when they are still out, she tells a relative that Raggett is driving her crazy and that she wants him out of her car.

But he does not budge. He keeps driving, with a blood alcohol content estimated to be between 0.169 per cent and 0.248 per cent. Just after 5.30am on Sunday July 25, 2021, on the Stuart Highway 13km north of Tennant Creek, driving at a speed somewhere between 116kmh and 136kmh, he loses control. The car rolls several times before coming to rest on its roof.

Raggett tells a passing motorist he has been travelling to Darwin and has fallen asleep – and that he is alone. The motorist returns him to his motel in Tennant Creek. Only at 8.30am, three hours later, does he finally reveal to his coach that he has been in an accident, and that someone is still in the car. Police are at the site within five minutes. Trapped in the passenger seat, Tenny is pronounced dead by ambulance officers.

“The facts do not disclose whether the deceased ultimately died as a result of your callous disregard for her circumstances, or whether her life might have been saved had she received timely medical attention,” chief justice Michael Grant later tells the NT Supreme Court, where Raggett pleads guilty to driving a motor vehicle dangerously causing death, and to failing to give assistance to the victim of an incident where he was the driver. “However, what is crystal clear and 100 per cent certain is that you abandoned all notions of common decency and humanity by leaving her alone, helpless and injured at the scene.”

Raggett is sentenced to four years and four months in jail, with a fixed non-parole period, backdated to the previous September, of two years and two months. He is also disqualified from holding a driver’s licence for five years. Latenzia Grant, whose skin name is Nappanangka, lives for 30 years and three months. She is the 22nd person to die on NT roads in 2021.

“She is a really positive role model for me because through the brave choices she has made in her life she shows me that I can also be free to make the right decisions for my future.” Lavina Grant makes this video ode to her older sister Tenny in 2013, long before the accident that will take her life and alter the trajectories of so many.

“She has taken the very brave step of moving away from family and community in order to have a better life with her baby daughter. Our community has a lot of issues and it is easy when you’re living there to get caught up in them. There can be pressure to follow what others do and sometimes this is not good, like drinking too much alcohol. Latenzia was caught up with alcohol but when she gave birth to her beautiful baby girl she realised how important her baby’s future is. She wanted to be positive and good so she made the choice of moving far away, all the way to Tasmania.”

Tenny’s death produces countless tentacles of sorrow. Beyond her grief, Amanda is angry at the silence with which she and dozens of women are met, during their hours-long vigil outside the local police station and the hospital, for details about the accident. “I find it hard to imagine a non-indigenous, white family would have been made to wait like that. Not only was the wait utterly agonising and unnecessary, it felt like she had been stolen, because we didn’t know where she was. Dead or alive, she was still ours,” she says, and cries. “Naida and I wanted to see her and say goodbye and I couldn’t tell Naida where her mother was.”

Tenny’s body is finally released to her family in time for her funeral weeks later on August 16, 2021. And only after, and still in mourning, do Amanda and Naida begin the long drive back to Hobart. There are no discussions in Tennant Creek about where Tenny’s child will live. Says Amanda: “We were continuing with her mother’s wishes.”

“She’s kidnapped us!” It’s not the opening line you expect when you step into Amanda Ducker’s Hobart living room, with its piles of children’s books and a coffee table covered with jars of coloured pencils. But the uproarious laughter that follows, and the tenderness that she shows her two young charges in the hours following this quip, suggests that while not every solution is perfect, some are more than bearable.

At 11, Naida has now spent most of her life in Tasmania, far from her birth family and culture, but with their blessing. Since December she’s also had a roommate. Her cousin Leslie Grant (known as Nunu) visited with his grandmother Linda – Tenny’s mother – last Christmas, and stayed. “Linda asked me to ‘keep the little boy safe’ down here,” says Amanda, who is now raising both children in Tasmania, with regular contact from their relatives. In the joy and sorrow that has infused so much of the relationship between these two families, Amanda is also dealing with the fresh grief of more loss, after her mother Meg died suddenly in June.

“They get to explore different places. It’s a city, and they get a better education,” says Lavina Grant as she witnesses from afar the progress of her niece and nephew. She is one of several adults who are in regular contact about the children’s upbringing with Amanda. “The family is happy with them being away and not being with their Aboriginal family,” she says.

“Tennant Creek is just getting to the point where kids are not learning, they’re wandering the streets all night and day. It’s getting worse,” says the childrens’ great aunt Josephine Grant. “The family has no issue with Amanda. She’s really good; she talks to us and we talk to her.”

It’s hardly the model that most authorities have in mind for at-risk indigenous children, however. In an effort to avoid creating a second stolen generation, governments around Australia have endorsed the Aboriginal Child Placement Policy, which, wherever possible, seeks to place indigenous children with kin or within their wider community, where they can also retain strong cultural ties.

Naida and her cousin, on the other hand, have minimal cultural input. Until recently, when they were able to access Warumungu language lessons on an app, there were no indigenous language classes at their Hobart school, and they played Minecraft while their friends, learned Indonesian. Their aunt Lavina has a new Warumungu book for them on plants and animals, a gift at the end of their long journey from Hobart to the NT to mark the second anniversary of Tenny’s death. And their grandmother Linda is due for another visit to Tasmania, when she plans to instruct the children in a bit of language and teach them about bush medicines; just as she hoped for her own daughter in Warrego a generation ago, she wants her grandchildren to “get more educated and more experience. We grew up in different ways in the NT, not much courage.”

As the woman who is raising these children day to day, Amanda Ducker is unperturbed about a dearth of culture in their regular schedules. “These kids are so profoundly connected with their families and they carry their culture within them. It’s not for me to try to recreate that here by attending events.” She is also fiercely protective about where they are being raised. “If you’re in a position where for whatever reason you need your child to be looked after by somebody else, who do you choose? Do you choose a stranger because of their ethnicity? Or do you choose another mother who you love and trust and have known since you were a child?”

She never envisaged her life unfolding thus. While she remains committed to her pledge to raise one woman’s child, but is in fact raising two, until very recently she held no legal authority for either of them. She has no grand plan for what happens next, either. “Keep them safe, keep them happy, just let them be kids,” is as forward as the future looks for now.

As she embarks on plans for a documentary about the group that she considers her extended kinship family, she envisages the cousins eventually making annual “pilgrimages” back to their traditional home, rather than spending all their time there. “This is not about extracting two kids, trying to educate them in a Western way, and then sending them home to face the consequences of that discordance,” she insists. “I want them to be able to walk in two worlds.”

Their grandmother Linda, although happy that they are being raised safely in far off Tasmania, already suspects that their futures will lie elsewhere, and that despite the potent call of country, they are already lost to the world she has always known. “They look at their other brothers and sisters and what they are doing in the Northern Territory,” she says forlornly from her home beside a creek bed near Mt Isa, where she lives in the wake of daughter’s death. “The way I look at it, they probably won’t come back.” b

Since this story was written, Amanda Ducker has secured co-guardianship for Naida and Leslie. Information about Amanda’s planned doco The Pledge can be found at her fundraising page: https://tinyurl.com/SupportThePledge

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout