Geoffrey Blainey defends his reputation

Geoffrey Blainey is rewriting history in his latest books – and quietly defending his reputation.

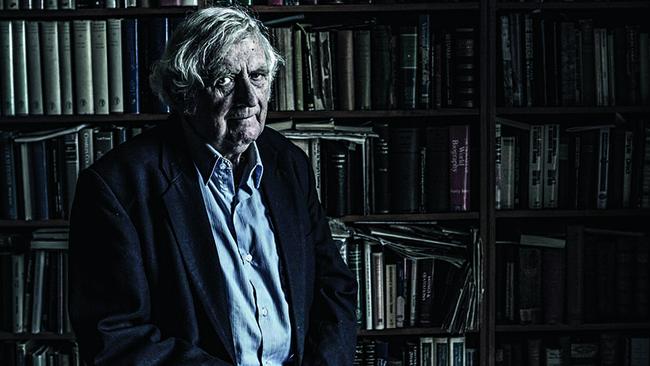

Geoffrey Blainey welcomes me into his inner-Melbourne terrace house with a certain rueful reluctance. “Should I be doing this?” he murmurs jocularly as his 86-year-old legs negotiate the carpeted stairs that lead up to his study. Australia’s most contentious historian barred the media from his home after the tumult of the mid 1980s, when his views on Asian immigration plunged him into a political maelstrom that irrevocably altered his public standing. Memories of that time – the abuse and threats, the protestors besieging his lectures, the academic peers who disowned him and the media scrum camped on his doorstep – are still vivid enough that Blainey would only agree to an interview at home on the proviso that its location and appearance were not disclosed.

“Once you’ve got a known address and something controversial happens, the press park outside all day,” he muses, using one of the disarming anachronisms that dot his speech. “And if they’re young journalists, they’ve got to get a story, haven’t they?” Actually, media harassment was the least he and his family endured during his days as a public controversialist, although the darker details are among the topics that are off-limits today. Three decades later, he lets only a limited circle of people know his email address and phone number. “Geoffrey still bleeds from that criticism and I think he realises it changed his career forever,” says fellow historian Keith Windschuttle.

It’s difficult to imagine a police escort being required today for Blainey, whose professorial mannerisms have become more pronounced as he closes in on 90. His speech has a stammering, ruminative rhythm that’s interspersed with the occasional wheezy chuckle; his perennially untamed hair is now white and combed haphazardly into place like tendrils of fairy-floss; his navy blue jacket, grey pants and open-necked shirt could have come off the rack at Fletcher Jones any time since 1973. His book-cluttered study is the sort of den you’d expect to find for a man who has been writing history for nearly seven decades. An antique wooden desk occupies the centre of the room, surrounded on three sides by floor-to-ceiling bookshelves filled largely with hardback tomes, the more antiquarian behind glass. Around it lies an obstacle course comprising tubs of documents, more books, a row of low wooden filing cabinets, old travel bags and a suitcase stuffed with unanswered correspondence. The mantelpiece over the disused fireplace is cluttered with holiday souvenirs, family snapshots, old letters and sundry detritus. Evidence of Blainey’s awards – the International Britannica, Order of Australia, Centenary Medal and Tucker Medal – is not to be found.

“Pretty, isn’t it?” he says, picking up a glittering chunk of quartz that sits on the mantelpiece next to a thank-you plaque from a Catholic social club in Bendigo where he once spoke. Having spent his early adolescence in the Victorian goldfield town of Ballarat, Blainey retains an enduring connection to rural Australia and the mining industry. The previous day he had been in Perth, speaking at a resources conference; next month he’s back in Bendigo, his father’s home town, talking at the library. “You always get a big crowd in a place where you’ve got connections,” he says drily.

The one concession to modernity in the room is the sleek Apple computer in the centre of Blainey’s desk, a device for which he professes conflicted feelings. “A computer is not very good – it takes up a key part of the desk, doesn’t it?” he says, indicating the keyboard’s inconvenient position in the exact spot he likes to position a book. Blainey wrote his first six books in longhand, based largely on his own longhand notes, and confesses a nostalgic fondness for the days when information was imprinted on your memory as your pen imprinted it on the page. “Cut and paste on the computer, it is really a terrible trap, isn’t it?” he says. “It’s like tearing off a limb and transplanting it; all the bones don’t connect.”

This wistful pining for the days of pen and ink is surely a bit of a performance, for Blainey’s output in the internet age has achieved a word count that would threaten the health of a younger historian. In the past decade alone he has published A Short History of the 20th Century, A Short History of Christianity, a book on Captain Cook, a history of Australian Rules football and a 900-page, two-volume epic, The Story of Australia’s People, which traces human settlement on the continent from the Paleolithic Age to 2016. And that’s not to count his revised editions of A Shorter History of Australia and A History of Victoria, several forewords and sundry essays and speeches.

It’s a prodigious output that is all the more remarkable for its quality. A Short History of Christianity was greeted with acclaim and The Story of Australia’s People – the second volume of which has just been published – has surprised many who would pigeonhole him as a rusted-on conservative. The book is an act of self-revisionism in which he revisits two of his earlier works, Triumph of the Nomads (1975) and A Land Half Won (1980), and radically updates and corrects them. The first volume of Australia’s People focused on Aboriginal Australia, and Blainey acknowledged his “dismay” that so much of his early work had been overturned by new anthropological and documentary research. Perhaps most surprisingly – considering critics including historian Henry Reynolds have lambasted Blainey for his “Edwardian” hero-worship of colonial settlers – the book added much new detail on the frontier violence meted out to Aborigines, acknowledging massacres and poisoning, and tacitly accepting Reynolds’ estimate of 30,000 indigenous deaths.

The second volume covers 1850 to the present, providing Blainey an opportunity to correct the flaws of A Land Half Won. “Women are very weak in that book,” he admits. “And that would be true of a lot of the books I’ve written. The first book I wrote, I don’t think there are any women.” Blainey is referring to The Peaks of Lyell, his vivid portrait of the mining communities around Queenstown, on the west coast of Tasmania, which began life as his PhD thesis in 1950. He wanders to his shelves, returns with the book and opens it to the first page. “I think the only reference it has to Aborigines is… can you see that paragraph?” He points to a sentence that refers in passing to “the wandering blacks” and laughs sheepishly. “You see, almost nothing was known of the Aborigines in that area then; now a lot is known.”

Those earlier books were products of their time, he says. “I wrote economic history, or history with more an economic slant, in the ’50s and ’60s and ’70s. In fact I was professor for a while of economic history at Melbourne University, and the economic history at that time dealt more with power, which women didn’t have in the economy.” In the new book he takes pains to reinsert women into the fabric of his story, writing of their role in domestic, political and economic affairs, and including notable individuals such as Dame Nellie Melba and mining entrepreneur Alice Cornwell.

It’s the final few chapters of the book, however, that are likely to cause most comment, for they cover a time when Blainey was a central player in the political controversies of the day. It was Blainey who lit the wick on the incendiary issue of Asian immigration in 1984 when he argued that an influx of Asian migrants was threatening the social fabric. And it was Blainey, nine years later, who famously attacked the “black armband” approach of many Australian historians, saying they overemphasised the racism and environmental damage of colonial era. So it’s surprising that his new volume makes no mention of either controversy, or of their attendant issues – the rise of Pauline Hanson, the “History Wars” and the national soul-searching over the Stolen Generations.

Asked about this, Blainey puts it down to ruthless self-editing. “I could have written quite a number of long chapters about the last 30 years, because I’ve lived through them and observed a lot of them,” he says. “But I cut a lot out of what I’d written, because if you’re writing a book or two books that cover an enormous span of time, it’s important that you don’t let the present become dominant. I felt I had to keep more recent history in proportion.” It’s a credible explanation, although not the whole story, because it turns out that Blainey is planning to address these more contentious issues in a separate book. It will be a memoir, in which he will correct the “myths” he says have built up around him. Genial he may be, but Blainey is quick to defend himself, as some of his fellow historians have recently discovered.

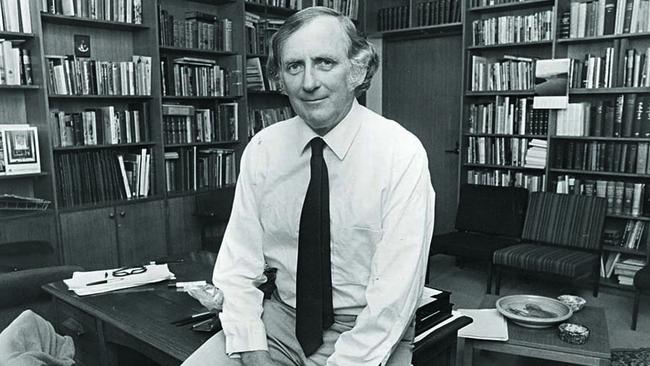

It’s almost puzzling, in an era when police hunt down teenage jihadis in the suburbs and nationalist politicians demand a ban on Muslim immigrants, to look back at the political storm that descended on Geoffrey Blainey more than three decades ago. At the time he was the Dean of Arts at Melbourne University and the country’s most popular historian. His 16 books included The Tyranny of Distance, which looked afresh at the nation’s past, and the ABC had commissioned a 10-part series from him called The Blainey View. Invited to address a meeting of Rotarians one weekend in Warrnambool in March 1984, he delivered a 35-minute unscripted address in which he declared that the high numbers of poor migrants from Asia were straining public tolerance at a time when unemployment was at its highest level since World War II.

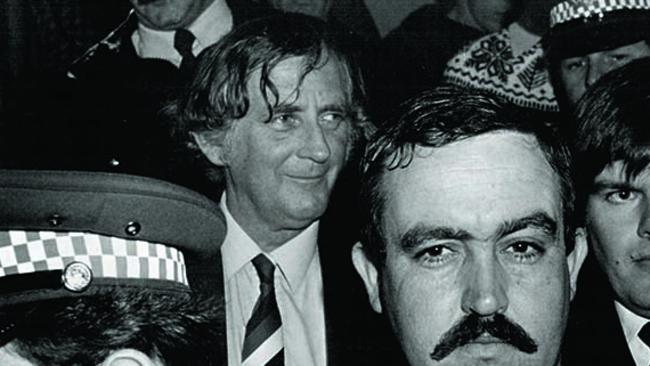

It was an unusually provocative observation for an academic historian, but no one could have anticipated the reaction it provoked. Within weeks, Hawke government ministers and ethnic community leaders were contesting Blainey’s claims, as commercial television aired rowdy public forums on “The Asian Invasion”. Two dozen of Blainey’s university colleagues wrote an open letter suggesting he was inciting racial hatred, and when angry protestors began laying siege to his lectures he was forced to cancel all public appearances and hire private security. At the height of the drama, according to a 2008 Quadrant article by Keith Windschuttle, members of Blainey’s family were threatened with violence and a bomb was placed outside a house near Monash University whose occupants shared his surname.

Blainey fired back with a book and speeches decrying Labor’s advocacy of the “Asianisation” of Australia, in the process becoming the bête noire of left-liberal academia. Henry Reynolds, author of Frontier, wrote a blistering dismissal of his work and pronounced he had “lost the respect of practically the whole profession”. In 1988 Blainey quit the University of Melbourne, explaining later that “there was no future for me there” – a claim that is disputed to this day. In the years that followed he criticised prime minister Paul Keating and the Pope for their statements on Aboriginal rights, praised the right-wing former Queensland premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen and insisted that the High Court had erred in its Mabo decision upholding native title. His “black armband” speech became the philosophical underpinning of the Howard government’s refusal to apologise to Aboriginal Australians for the Stolen Generations.

Today he’s reluctant to revisit those events. “It’s a long while ago,” he demurs, adding that he stands by his statements on Asian immigration. “I was simply saying that social cohesion is important. And I see no reason, looking around me, to change that view, that social cohesion is important.”

Blainey may have relished the battle but he was deeply wounded by its outcome, according to friends. He had started his career as an outsider, a rural Methodist minister’s son who entered Wesley College and then university on scholarships and made his living at first by writing commissioned corporate and civic histories. His approach – narrative history grounded in primary research and rendered in lucid, pithy prose – caused some historians to sniff about poor footnotes, yet he had risen to become head of history at the nation’s most prestigious university. After quitting that post, though, he was back to the tough scrabble of being a working writer.

“There’s no doubt that in a sense his career is in two parts – before 1984 and after,” says Richard Allsop, a senior fellow at the conservative Institute of Public Affairs who has written a PhD thesis on Blainey’s work. “He was perceived very differently by a lot of people after that.”

Last year Allsop, an admirer of Blainey’s and a former Liberal government adviser, discovered just how deeply Blainey was affected. Allsop had spent nine years working on his thesis with the historian’s co-operation, gaining access to his scholarly papers and interviewing him on 10 occasions. But after Blainey read the finished work he began withdrawing permission for use of certain material. Allsop complied and was revising the thesis for publication as a book late last year when he got a letter from Blainey’s lawyer threatening legal action if publication went ahead. The book has now been cancelled, and Allsop will only say he thinks it’s “sad” that Blainey felt the need for such precipitous action. His account was by all reports extremely sympathetic to its subject. “Clearly, what happened in the 1980s was deeply painful for Blainey,” says Allsop’s supervisor on the thesis, Monash University history professor Bain Attwood. “Perhaps not surprisingly, he hasn’t been able to come to terms with it.”

In March, Blainey’s lawyer fired off another letter, this time to one of his former students, Frank Bongiorno, now an associate professor of history at the Australian National University and author of The Eighties, which devotes a chapter to the Asian immigration debate. Blainey contested the book’s accuracy, and although Bongiorno declines to comment, the paperback edition will be slightly revised. The book’s publisher, Chris Feik of Black Inc, says there is no ongoing dispute – which must be a relief for Feik, who also publishes Blainey’s wife Ann (I Am Melba) and Blainey himself (A Game of Our Own).

Asked about these incidents, Blainey again demurs. “I don’t think I would comment on that,” he mumbles. But his occasional asides hint at the resentment he nurses. Asked which of his books are taught in Australian schools, he replies that he’s not sure but “I would have books on more syllabuses in South America than in Australia”. Remarkably he’s won few state or federal government book prizes, although this month the first volume of The Story of Australia’s People was shortlisted for the Prime Minister’s Literary Awards. And as the Bongiorno episode shows, he takes a keen interest in how other writers portray him. “I’ve read several accounts lately of events of the 1980s and they’re so inaccurate – provably inaccurate,” he says. “And one of the things that’s astonished me is that they have altered the whole chronology of it, which is unforgivable in a historical sense – to change the chronology of events so you put your argument in an advantageous position.” It’s because of this, he says, that he will correct the record in his autobiography, which he started writing more than a decade ago and set aside. “I will say something,” he says, “because, well, I just have to, don’t I?”

A couple of years ago Keith Windschuttle appeared alongside Blainey at an address to a high school on Victoria’s Mornington Peninsula. Windschuttle was surprised to discover that the elderly historian had driven down in his own car, and when Blainey offered him a lift back to Melbourne, Windschuttle hesitated. “I thought, ‘Shit, this is going to be risky’,” he recalls. “But no, he was entertaining and chatty all the way home, and his driving was impeccable. I think he realises how important it is to keep your mind active.”

Blainey’s driving may even have improved since – in March he had cataracts removed. “I had a period of about six months where my eyesight was deteriorating and I couldn’t understand it,” he recalls. “I thought it might be the windscreen of the car and I got new glasses and so forth. I was reading with the aid of a magnifying glass and a torch. And it slows you down, because I was missing commas and decimal points, little things like that.” Since the operation, he reports with pleasure, “I can see things I haven’t seen for years!”

The image of Blainey labouring over the manuscript of The Story of Australia’s People with a magnifying glass and torch says something of his work ethic. He is still at his desk by 8am most mornings, although he no longer goes out for lunch daily. He still does most of his research at libraries rather than on “the machine”, as he calls his computer. And his powers as a stylist have hardly dimmed, as Australia’s People shows – it’s full of his trademark felicitous phrases and succinct snapshots: describing a massive dust storm in 1902 he writes that it spread across the snowfields “like pepper on sugar”; the rise of vegetarianism in the 1960s, he remarks drolly, foreshadowed our own era of “implacable dietary fears”.

That latter phrase gives a flavour of Blainey’s withering attitude towards many causes of the Left; his new book likens the Green movement to a secular religion and disputes the view that Australia is a particularly racist nation, two familiar themes from his speeches and essays. Its conclusion finds him venturing back into the vexed issue of immigration when he examines home-grown Islamic extremism, which he believes is placing greater strain on the social fabric than the Asian immigration issues he once warned about. “I don’t think there’s any doubt about it,” he says, noting the public calls for a ban on Muslim immigration. Blainey’s own view is that this is “a bit harsh”, but he argues that the problems he outlined in 1984 – poorly educated migrants entering the country with little hope of contributing to the economy – are now overlaid by the fear of Islamist violence.

“What’s happened in the last 15 years would have been seen as absolutely impossible in 1970 or 1980 or 1990, wouldn’t it? Just taking the terrorist attempts which were thwarted – for example, the MCG Grand Final – there are quite a number of those, some of which we know, some of which we don’t. They have had an enormous effect on people’s sense of wellbeing and security. The official inquiry into the Martin Place siege shocked the public more than anything – the fact the authorities couldn’t cope with it, and appeared at times to give the terrorist preference over the people who were in his captivity, that’s been a profound shock.”

Does Blainey believe Muslim immigration should be reduced? “I wouldn’t know the answer to that unless I had access to information about the extent of the security problem,” he replies. It’s an artful dodge which he refuses to be drawn on. “You have to be careful when you get old that you don’t get into a controversy that’s quite unmanageable,” he says wryly. “Controversy is incredibly demanding if you take part in it in public, particularly if you’re doing it on your own.”

Whether Blainey’s short-listing for the Prime Minister’s Literary Awards signals a late-career renaissance of his reputation remains to be seen. Some of his confrères on the conservative side of the History Wars sound like they’d like to see him don his armour one more time. “He liked the role of controversialist in the 1980s,” says Windschuttle, “but I don’t think he likes that role now. You can understand that – he’s well into his 80s, and having public disputes and being unpopular is a great strain. I mean, he’s Australia’s greatest historian, there’s no question about that, and he doesn’t want to sully his reputation today.”

Stuart Macintyre, emeritus professor of history at Melbourne University, says Blainey’s recent output shows “no suggestion of a decline in his curiosity or ability to bring fresh insights to large and well traversed subjects”. Macintyre was among Blainey’s critics in the 1980s but helped organise a Melbourne symposium in his honour in 2000, and co-edited a book-length assessment of him. “Some historians disagreed with the positions Geoff advocated in the ’80s but many of us regret very much the way that these were inflamed,” he says. “I’m not alone in admiring him greatly.”

Blainey ends The Story of Australia’s People on a note of optimism that has been a familiar refrain in his work: he finds commonalities in the stories of indigenous and non-indigenous people who settled on this continent and survived despite their isolation. It’s the wide-angle viewpoint of a historian whose own life has encompassed a timespan of unimaginable change. “My belief is that this is about the most fortunate period in the history of the world. We haven’t had an all-out war since 1945 and the number of people in the world who have enough food, have a reasonable life – it’s enormous compared to the number that lived in 1945… I think this is an incredibly fortunate period to be alive and I don’t agree with some of the historians or Aborigines who see the history of Australia before 1788 as paradise. I see it as ingenious and having great achievements but I don’t see it as paradise in the way they see it. I think I ended the book very positively because I was thinking of 60,000 years, stretching back into time.”

One would have thought such an ending to such a book might qualify as Blainey’s final statement as a historian, but that’s evidently not the case. There’s the autobiography, of course, and after that he thinks another big book is possible. “I’ve still got books in me, yes.” He laughs mordantly. “God willing – because, after all, I’m old.”

The Story of Australia’s People: The Rise and Rise of a New Australia by Geoffrey Blainey (Viking, $49.99)

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout