David Attenborough: restoring the world’s sense of wonder

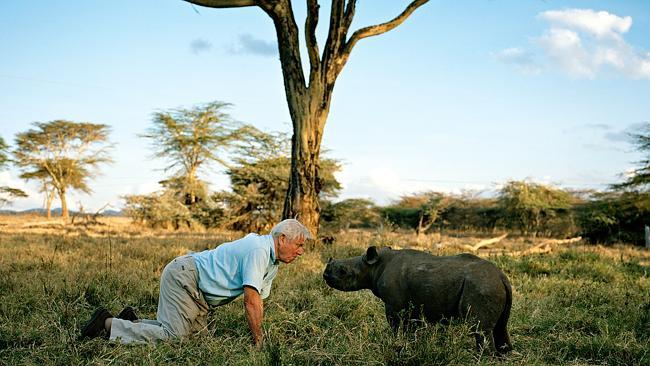

Entering his tenth decade, David Attenborough is still sharing his passion for the natural world – and ideas about how to save it.

The first time I went to Sir David Attenborough’s house, he asked me to guess the nature of a fossil. I got it wrong. “Dinosaur poo!” he corrected gleefully: glee not in my error, but in the joyous fact that fossilised dinosaur turds exist and he had one in his hand.

On this second visit, a few years later, there is something more substantial than a coprolite to show me. It’s a new library. With a gallery, imagine that? Beautifully designed, full of natural light. And it’s as remarkable for what it doesn’t contain as for what it does. There are no photos of Attenborough with gorillas, Barack Obama or any celebrity for that matter. There are no awards in sight, even though he’s won Baftas for work in black-and-white, in colour, in HD and in CGI. There are books in the thousands. Their ranks are broken up by enthralling chunks of tribal and ethnic art. At one end there’s a grand piano with a volume of Bach on the music stand; he can play to a very decent standard. There are no family pictures. No photos of his late wife, Jane; they were married in 1950 and she died in 1997. No pictures of his son, Robert, or his daughter, Susie. None of his late brother, Richard, who was his neighbour in Richmond, London, for most of their lives. Doubtless these exist, but they’re not on view. Not here.

All the same, this is both a personal and a public space. It’s about who Attenborough is and how he chooses to present himself to the world. That means it’s a space about passions: passion for life, for the world and for the way we humans fit into it. As a reflection of the man we know, it does a good job. It’s a room where you could spend a day alone, find treasure after treasure: things on which you can feast your eyes and mind. But when the man who built the place is present, it all rather fades into the background.

He’s 90 in May. He has a program coming out, Attenborough and the Giant Dinosaur, about the biggest dinosaur of all. He recently completed another program about bioluminescence, and yet another on the Great Barrier Reef, in which he went 300m below the surface in a submersible.

There is a moment when people in public life reach a certain age and become Wonderful. Then they get called Living National Treasures: celebrated for what they’ve done, rather than for what they’re going to do next. By that definition, Attenborough is not Wonderful at all. Nor is he a Treasure in the strict sense of the term: the future is what consumes him. What matters about him is that his views and passions are essential to the way we all look at life on Earth in the 21st century.

Which brings us straight to Paris. Here, in December, the politicians reached the beginnings of an agreement on climate change and, with it, a strategy to reduce the rate of warming. “Nothing is as good as you wish it to be, but it’s very much better than it was in Copenhagen,” Attenborough says. He was there to promote the Global Apollo Program, which operates on the premise that if we can find the money and the expertise to put a man on the moon, we can create enough renewable energy to power humanity into the next century. It comes down to the technicalities of transmitting and storing that energy. Attenborough is convinced it can be done, but only if it is treated as a space-race priority. That means accepting the truth: that climate change is a genuine crisis in the life of the planet.

He came out on climate change in 2004 and was accused by some of leaving it rather late. This reflects the sense of responsibility that defines him: he’s not one to go off half-cocked. He knows a statement that comes from him will be treated with immense respect, so getting it right matters. And when he’s got it right, he gives it the lot. “When I look back to some of the programs I’ve made, I ended up saying, ‘Look, we’re wrecking the world.’ Now people believe it and understand it. The Americans have come round and this country has come round, and it didn’t start that way. But in this country, at least, it would now be political suicide for a party leader to say, ‘I don’t believe in global warming.’

“People say to me, ‘Why do people still say it’s not happening?’ And I say, hasn’t it occurred to you that it’s rather nicer to say that it’s not happening? You don’t have to worry or spend money and your business isn’t going to be in peril.” Attenborough has not slipped into an old man’s passive acceptance: the what-will-be-will-be mentality that makes life comfortable for those who find life increasingly difficult.

A sense of the fragility of the world is intimately connected to an appreciation of its wonders. This sense of wonder can be called childlike, but that doesn’t make it childish. In maturity, wonder develops into a perpetually life-renewing thing. It began for Attenborough when he started collecting fossils as a boy and it has continued with his joy in the titanosaur of Patagonia, which is the subject of Attenborough and the Giant Dinosaur. Attenborough collects stuff. Like the books, like tribal art, like fossils, like pottery. When he likes something, he likes a lot of it. He also likes the idea of the quest for completion, the crazy idea of encompassing all knowledge. It’s an impulse that lies behind the many epic TV series he made. Life on Earth? What, all of it? Well, yes, actually.

Which explains why the opportunity to visit Patagonia to make the program about an unnamed species of titanosaur was irresistible. It was found in 2014, first from a femur sticking out of the ground, and now it’s claimed as the biggest dinosaur of them all. “They’ve got about 60 per cent of the skeleton, which is a lot, and they’ve done the statistics and they say it’s a world champion.” The most generous estimates put this new contender at 40m long and 20m tall, with a weight of 80 tonnes, or more than a dozen African elephants. Attenborough’s face lights up as he talks me through it. Perhaps curiosity is not a cat-killer, but the world’s great life-giver.

The same urgent curiosity took him down in a submersible off the Great Barrier Reef, a daunting ordeal to anyone with even a hint of claustrophobia. “It’s nothing, but then I don’t have any imagination,” he said. “You get in and you’re in a big plastic dome, and you look around and it gets darker and fish go past and you can sit there eating a bar of chocolate. When we were at 300m, a deep-sea grouper came up to look at us, a huge thing about 2m long.”

Which is a ballsy effort, even for a stripling of 89. But it all comes not only from the sense of wonder at what the Earth shows us, but also from the wonder that is common to every teller of tales. Throughout his broadcasting career Attenborough has brought together perplexingly different things and made from them a coherent narrative. People notice the exposition, the performance and unfading delight that comes from every on-camera encounter with the wild. But there’s more to it than that. Above all, he is a tale-teller of genius.

And if the story has an uncomfortable conclusion, he is not a person to duck it. Each question about the future of the planet and the creatures that inhabit it leads to an overwhelming problem. It’s overpopulation. Here, again, Attenborough has a conclusion and a view. “It seems to me that every one of the ills of the past 200 years – hunger, famine, loss of identity, forests disappearing, loss of dignity, overcrowding, loss of countryside – it’s all to do with increased population. The only way you can deal with this situation – well, I can’t see myself getting up on a soapbox and saying, ‘Stop having children’ – is when people are better off without so many children. Anywhere that women have control of their bodies and education and are literate and politically independent, the birth rate falls. Kerala in India is an example of that.”

It has always been Attenborough’s way: not just to point out how humans have got it wrong, but to follow up with how we could put it right.

Attenborough began his television career by showing us nice, fluffy animals. Now he is the most important spokesman we have for the most serious long-term issues that face the entire human race. How did that happen? “You have to live long!” he says. “It’s not a role I have consciously taken on. People have put it on me. Certainly, when I started, if you were the only television voice in the land, the obligation of being pretty damn sure of what you were saying was considerable.”

He has brought the world’s great wonders into our living rooms. And this willingness to share the creatures and emotions of wonder has slipped beneath our guard and gained our trust. That trust has extended to presidents, and led to the meeting with Obama at the White House. “He said to me, ‘I was born and brought up in Hawaii. That’s why I love nature, I spent so much time with the sea.’ I said, ‘In that case, Mr President, you must know the humuhumunukunukuapua’a.’ He said, ‘You know that?’ Not only that, I kept them, and the humuhumunukunukuapua’a is the state fish of Hawaii.” The story and the wild name are expressed with immense panache. “And he seemed such a genuine man, a very nice man, and it was very nice to meet him.”

Next, we’re tacking away from global politics and saving the world, and we’re back down to the thrilling minutiae of life. Attenborough’s program on bioluminescence is gloriously obscure, and in its way it’s as thrilling as anything he’s ever done. Bioluminescence is what fireflies do. “We’ve been working with a camera that is 4000 times more sensitive to light than normal cameras, so you can film in a serious way, open up areas we haven’t seen before. We went to a woodland in Pennsylvania where there are 17 different species of firefly, each with its own flash code. Why are there so many species?” Darwin’s question, or one of them, pursued once again, this time from a thrillingly unexpected direction. “There are even luminous earthworms in France, and the question is, why on Earth are you luminous? I think we’re going to suggest that it’s a by-product of waste disposal.”

Attenborough hates lazy cynicism, hates laziness of any kind. He’s good company, always: even in a formal interview he prefers conversation to monologue. The lightness of touch he has always been able to give us when he speaks to camera can shift effortlessly into knockabout humour. If he knows that you share his delight in the wild world, his talk becomes deeply generous: he’s a great giver of himself.

I’ve seen him deal with the passions of children with immense seriousness, giving dignity and deeper meanings to the matters that have seized their imagination. He is always being asked how he got his passion for the wild world: he always responds: “How did you ever lose yours? Because I never met a child who wasn’t interested in natural history.”

How many people on the planet have been influenced by Attenborough? How many have understood that a love for the wild world is as important to a fully baked adult as it is to a child? How many people have had their lives enriched by that understanding? The wild world is the birthright of the human race and Attenborough has done more than anyone else on Earth to give it back to us: to restore it to those who lost it or temporarily mislaid it. Attenborough is the man who gave us back our own.

© Sunday Times, London

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout