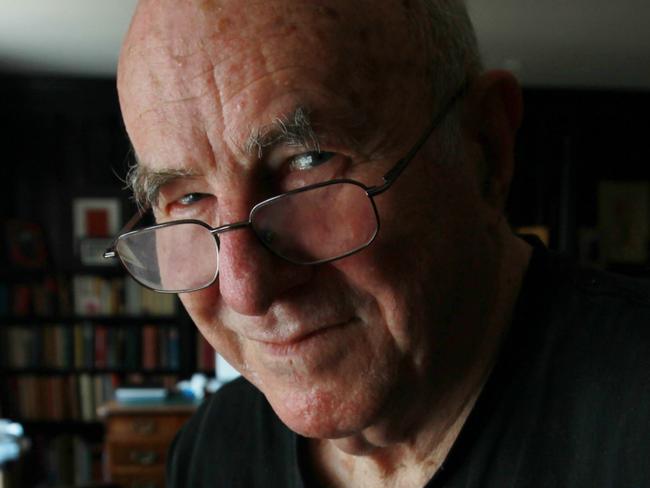

Clive James: life, death and my next great work

In a 2015 interview, Clive James contemplates the legacy he leaves, the void that awaits – and his final wish.

The old yellow envelope marked “James, Clive” comes with a strict instruction in thick blue ink: “NOT TO BE OPENED UNTIL HIS DEATH!”

“What is it?” asks Clive James, our dear Flash of Lightning, wheezing at a long hardwood desk in his Cambridge terrace home warmed by spring light. The document has gathered dust in a newspaper reference library since it was written in 1985; a five-page story of his life as a poet, novelist, essayist, critic and television superstar; a story without an end. “It’s your obituary,” I say.

He beams. “Oh, you must mention this,” he says, fixing his glasses to read a pre-emptive summation of his life, penned long before he met the “gentlemanly cancer” now killing him slowly. He roars with laughter and his 75-year-old lungs, shot with emphysema, can’t accommodate the air intake and he coughs and splutters. “Oh, this kills me,” he smiles, enraptured. “Oh, I’m gonna die! Listen to this…” He holds the obituary high, orates like the eulogist at the funeral service he doesn’t want: “Some devotees even regarded James as a cross between Shakespeare and Noël Coward … high praise indeed!”

The obit needs a rewrite. It’s a paint-by-numbers chronicle of how, from the early 1960s, “The Kid from Kogarah” lit a threepenny bunger beneath the pristine and pale white backside of Britain’s literary elite. No mention of his siblings, Mozart and Virgil. No mention of his best friend, Dante Alighieri. No drama, no romance, none of Clive’s beloved “sssssstrrrructure!”

“Well, it is useful to know where your story is going to end,” he says. This story, for example, will end by the lapping waters of Circular Quay, beneath the comforting shadow of the Sydney Harbour Bridge, some time after our hero has sucked on a tropical fruit ice block, faced the demon of his great mistake and stared, content, into the black void of his death.

“It’s about knowing where things fit,” he says. “I’m a great believer in the magic sentence, but I turned into a better writer when I realised what really mattered was the magic paragraph. It’s not just attention-getting phrases. It’s the way words click together, the way a line turns, the way the start of the next line expands the idea or makes it a revelation, the sense that everything is carefully shaped, the way the long sentence prepares you for the short one.”

Clive loves language and linguistics and kookaburras and Katharine Hepburn in full cinematic flight and Napoleonic history and the jokes of Peter Cook and Game of Thrones and Melbourne trams and Cathy Freeman and the atomic energy of his granddaughter. Clive hates the cold. “The wind,” he shivers. A chill blows in from his rear stone garden courtyard where a Japanese maple, planted by his daughter, stands leafless. “I think I should close those doors.”

I’ve been technically dead now for several years.”Standing takes concentration. Shuffling across wooden floorboards in black socks takes effort. He’s alone but not lonely here. His lifelong friends are with him in this well-kept exit room, walls of books, rows of Russian writers facing the French; a wall of German greats leading on from the English-speaking shelves of Auden and T.S. Eliot and D.H. Lawrence. A small kitchen built for function only, breakfast plates and a tub of mint-fresh dishwashing liquid rudely interrupting a thousand perfect book spines. A packet of paracetamol on a bench, a brown fruit bowl filled with bills and letters.

The internal staircase is harder to climb each evening. Up there waits a bed with a sweat indentation the shape and depth of his thinning frame, where he lies for hours, waiting on sleep, dreaming about skipping down to his favourite Cambridge cafe; backyard cartwheeling with his wondrous granddaughter; dancing his beloved and practised tango on any number of tiled floors.

Instead of enacting these dreams he reaches to his bedside table, his watch hanging loose on his wrist, scribbles his thoughts in a black and red notebook. And after three years of poetic scribbling he transforms what it is to be dying, turns his end into a masterpiece. “I’ve been technically dead now for several years,” he says.

A dug-out skin cancer wound the size of a quail egg erupts beneath a white gauze pad fixed to the left side of his forehead. It wasn’t the soft Cambridge sun that did that; it was his boyhood sun from home, a place he is now too ill to return to, no matter how sweetly it calls for him. “It weighs on me,” he says.

He hasn’t been home in years, yet on his bed upstairs he can see his beloved Sydney with such clarity he wonders sometimes if he’s hallucinating. He sees the short pants of his youth. He sees fat Sydney rock oysters and Australian white wines to wash them down. He sees piston rings strewn through the Tempe dump. Home is his default daily web search subject: its developments, its politicians, its poets, its gradual growth into “this new, strange and wonderful place” where “plenty feel superior but nobody feels inferior”. But he can’t hear real whipbirds on the worldwide web. He can’t taste a summer whiting caught on a handline, scaled and cooked on a beach fire.

Clive once appreciated Cambridge for its sprawling flower-lined colleges where he trod the boards for the mighty Cambridge Footlights drama club, where he walked on air through the Wren Library with its original Shakespeare prints and work notes of Isaac Newton. He now appreciates this learned city for Addenbrooke’s Hospital, where brilliant people of medicine dedicatedly halt his demise up to four times a week.

He rations time and energy now like he once rationed cigarettes at Sydney University. He sleeps long and deep. Some mornings after breakfast he will climb those stairs and slip straight back into bed, let the guilt of idleness build into a 5pm poetry frenzy. He now reads and writes in waiting rooms. If an idea strikes anywhere he has a pen to scribble it in a small notebook or the end pages of a novel. Scribble, scribble, scribble about language and love and loss until the doctor calls him in for another round of chemo to fight the relentless CLL – chronic lymphocytic leukaemia – slowly and surely ending him. Breathe through a scarf. Avoid the cold. Don’t dwell on love. Don’t dwell on loss. Scribble poetic lines about birds and the Manly Ferry of his youth and the quietly miraculous way dew falls on morning leaves and then humbly submit his arse to another doctor’s biopsy. “It’s a farce,” he says. “It’s not even a nightmare. But one small bonus, right now, is I’m getting increasingly clear memories of childhood. Whereas I can’t remember what I did last week.”

A thought comes to him. “I had a bone marrow biopsy last week. Who wants to remember that? In fact, I might write a poem about that. It’s like having a London bus crammed up your arse.”

Has one long hour truly come to pass,

With this London bus crammed…

“I’ll be going into chemo again soon,” he says. “It’s serious. I was last in chemo five years ago and it was a huge success. The CLL retreated and stayed there a long time. An unusually long time. A tactless doctor said, ‘Well, congratulations, of all the people who were in your chemo class, you’re the last one left alive’. Thanks a lot.”

I was a young man for too long.”Here’s that voice, throatier than it was on all those masterful ’80s and ’90s chat shows and documentaries, but here still, wry and deep, even more bone-dry now he’s waltzed so many times with his scythe-wielding stalker. The voice that invented a new form of television: the brilliant smart mouth commenting dryly on collected video clips, versions of which now populate every pay TV channel across the world. The voice that invented a kind of “simultaneity” pop culture journalism, a sweeping kind of writing and print wit that could funnel six or seven simultaneous ideas into the criticism of a single work. The voice of a Kogarah outhouse dweller and a Queen’s CBE, of a tireless literary wonder who has gifted the world more than 40 books, six volumes of verse, five volumes of autobiography and one immortal assessment of Arnold Schwarzenegger: “Like a brown condom full of walnuts”.

The barbs are fewer now but the sting still smarts. “Tim Flannery – one of the great comedians!” he laughs. “America – more foreign to me than Japan!” he sings. “I’m the one who knows about Stalin,” he hollers. “Your average Australian politician knows nothing about Stalin, just behaves like him.”

His writing desk is heaped with poetry books; John Howard’s two recent political tomes; an exhaustive analysis of Dante’s writing by his wife and lover of 50 years, Cambridge scholar Prue Shaw, who lives in a separate house a few blocks from here, for reasons relating to his great mistake. A black and white photo rests on a bookshelf: Clive in 1970s Florence, a young dad with the elder of his two daughters, Claerwen and Lucinda, on his knee; fit and surly, Jackson Pollock with child. “The young man,” he says, shaking his head ominously. “I was a young man for too long.”

So close to the end he recalls the beginning too clearly. Time is elastic, he says, like memory. “Memories,” he asks himself in a recent poem, Star System, “where can you take them to? Take one last look at them. They end with you.”

He sees his mum and dad from the vantage point of a six-year-old boy, careful not to look too long. He sees them reading Dickens together aloud, thrilled by the language. He sees them before a living room wireless, laughing. “I never don’t think about my mother,” he says. “But I try to keep it limited or it would incapacitate me. Thinking about my father incapacitates me. I think about it as little as possible. If I think about when he was in the prison camp it would stop me in my tracks, it’s just too big a subject.”

Two significant telegrams landed at Clive’s working-class south Sydney home when he was six years old: one telling his factory worker mother, Minora May James, that her husband, Sergeant Albert James, had miraculously survived a World War II Japanese prisoner of war camp; another, later, informing Minora that the plane her husband was returning home on was caught in a typhoon and crashed in Manila Bay, killing all aboard.

In 1980’s hugely popular Unreliable Memoirs Clive recalled “seeing the full force of despair”, watching his mother weep for days, to the point where he was “marked for life”, “never quite all there”. Unreliable Memoirs was a light book of comic genius – the suburban fence-hopping, trouble- making adventures of his self-dubbed superhero avatar “the Flash of Lightning” – but it was designed to mask the stained-glass psyche and fear at the core of its author.

“There you are,” he says. “That’s the first hint of a great truth that I’m still dealing with. The book itself is happy because it’s about Australia, but it’s a book written by a quite seriously troubled person.

“Your expectations of life are usually expectations of immortality. But if you’ve seen very early in your life someone close to you quite arbitrarily wiped out, that alters the expectation. What was security becomes insecurity. It’s really what happened. You could go on and on just writing about that or you could realise that it set up a polarity in which you’re obliged to compensate for this feeling of insecurity, by actually getting something done, leading the life that your loved one might have led. My father, I think, would have really been something, but I’m only guessing. What I did with my work was to make up for the life that he and my mother didn’t have.”

He sighs weakly, a sickness rattle from his chest. “I don’t think about them all the time because I would do nothing else. I would die of grief while I was walking. I don’t want to do that. You go to Jerusalem and meet people who, if they spent too much time thinking about their heritage, would die on the spot, so they get on and make the desert bloom.”

And Clive stands, not to make a desert bloom, but to make a toasted sandwich with at least five layers of sliced bright pink packet salmon. “Don’t watch this,” he says, wrapping his lips around an open sandwich resembling a Himalayan mountain range. “My appetite is down,” he says. “But it’s still there. I get weird cravings for things like ice blocks and orange juice frozen on a stick.”

I have a proof copy of his latest book of poems, Sentenced to Life, open at his writing desk. It’s the 37-poem culmination of all that deathly scribbling, an artistic endeavour that feels as searingly close to a satisfactory conclusion on existence as anything any Australian writer has conceived.

I’m living far, far beyond my luck and I won’t be stunned if something goes wrong.”“This is all extra time now,” he says. “I’m not scared of not knowing anymore. I’m living far, far beyond my luck and I won’t be stunned if something goes wrong. I didn’t expect to get that book done.” His left hand reaches across the desk, casually grabs the proof copy. “Which one are you reading?” he asks.

The proof is open at two adjacent poems, Change of Domicile and Rounded with a Sleep. The first speaks of “one house more” that he will be going to after this Cambridge house, a dark and austere place – the void – “lacking the pictures and books that are here. Surround me with abundant evidence I spent a lifetime pampering my mind”. The second finds Clive awaking at his writing desk from dreams of great oceans and his grand-daughter, “a natural star”, splashing about in perfect family beach scenes. Both poems touch on his great life flaw – faithlessness – and his great mistake, the thing that threatened those family scenes, a love affair with former Australian model Leanne Edelsten that was splashed across the world’s tabloid media three years ago with wrecking-ball sensitivity.

I left it late to come back to my family.

I just wish the mistake were rare, and not so frequent I could weep.

Clive scans the open proof pages, covered in my knee-jerk reactions and amateurish pop psychology pen scribbles attempting to analyse such fearless soul coughing: “Heartbreaking!” “Chills!” “I hope she forgives you?” The poet laughs knowingly.

But I shall have time to reflect

That what I miss was just the bric-a-brac

I kept with me to blunt my solitude,

Part of my brave face when my life was wrecked

By my gift for deceit

Truth clears away so many souvenirs

Beside these words I’ve scribbled in capital letters: “PRUE, COME BACK!” Clive gives a half smile, hands the proof back, has another bite of his sandwich.

A knock on the front door. “Parcel for you Mr James!” says a plucky delivery man. He’s a fan. The parcel was given the wrong address but the stout-hearted courier walked up and down Clive’s street until he found its rightful owner.

“Now that’s fame,” Clive says, opening the parcel at his desk. “When a parcel finds you with the wrong address on it. I don’t mind being anonymous and solitary because I’m naturally both of those things, but television makes you recognisable for decades afterward. I haven’t been on the air since the year 2000, but I still meet people who say they enjoyed me on tele last week.”

The parcel contains an American version of his Poetry Notebook 2006-2014, his exhaustive exploration of poetry craft after 50 years of absorbing and writing poems. “Fame is very artificial and you’ve got to get used to it and you better also learn not to expect it because one day it will go. People get so used to being recognised that they feel sick if they are not.” He whispers an aside: “I could name names.”

“Fame’s very corrupting. You think the whole world will look after you. Well, the world isn’t really like that. I never depended on it and now I definitely don’t. If you’re in hospital and you’re looking at the walls and your own urinary tract is hanging on the wall like a Rothko, it’s nice to be anonymous.”

He chuckles to himself, scanning his book. “Anyway, the real condition of mankind is to be someone really valuable like a nurse or a doctor. It simply is more important to be a farmer or to clean lavatories properly, all those things are more important. The world doesn’t need more writers.”

The world doesn’t need more writers.”He opens the hardbound book down its centre, flexes its spine: “Always break a book in like this. Don’t read it out of shape.” He thumbs the book’s jacket paper stock. “Mmmm,” he says, approvingly. “That’s quite handsome.” He coughs up some phlegm and chokes it down again.

“Why do you keep writing so much?” I ask.

“Good question,” he says. “Best question there is.” He sits. “One, a character flaw,” he says. “I was born to be in the limelight. The other reason is out of a capacity for admiration. I wanted to join those people who were seeing things in a way that I admired. I wanted to be among them. But don’t underrate the importance of the first one. Some people think it’s their natural condition to be in the limelight. I’m one of those. It’s just that I’m a reclusive version of it. I’m a limelight recluse. But it always comes from a character flaw. Everyone can’t be a star. There’d be no space between the stars.”

He stands again, shuffles to his refrigerator. “I need to walk,” he says. “It’s called ambulation. I need to ambulate or my thrombosis catches up with me.” He leans down to dig through his buzzing freezer. “Do you mind if I eat an ice block?” he says. He unwraps the tropical fruit ice block, licks it a few times, bites into the top. “This is a unique experience, you know. No one has ever seen me eat an ice block.”

He stands, ambulating by the table, as I flip to another poem in Sentenced to Life.

“This one hurts to read,” I say.

“Glad to hear it,” he says.

It’s a piece called Holding Court. Clive looking back at all those years of entertaining, all those strokes of wit, all that amusement he gave his friends, he gave the world, and wondering where it fits in the story, so near now to the end.

You were the ghost they wanted at the feast

Though none of them recalls a word you said.

“I’m hoping the reader will contradict that,” he smiles. “But time always takes care of the questions. Do you know Maria Edgeworth?”

No. “Do you remember Bulwer-Lytton?” No. He shrugs. “I’ve got to be ready for that.”

The book began as a sweeping contemplation on his death. It ended as something else, revelatory and true, a tribute to what we have left when the fire fades, when the limelight shifts focus, when the strokes of wit are forgotten, and we see, at last, who still stands by the darkening embers. Prue. His daughters, Claerwen and Lucinda.

“Dare I say that it gradually became clear to me that that is what I was up to,” he says. “It didn’t start off that way. I was writing about being dead tomorrow. And then I started thinking, ‘Well, this is a finale. You’d better make it good’.”

Japanese Maple

Your death, near now, is of an easy sort.

So slow a fading out brings no real pain.

Breath growing short

Is just uncomfortable. You feel the drain

Of energy, but thought and sight remain:

Enhanced, in fact. When did you ever see

So much sweet beauty as when fine rain falls

On that small tree

And saturates your brick back garden walls,

So many Amber Rooms and mirror halls?

Ever more lavish as the dusk descends

This glistening illuminates the air.

It never ends.

Whenever the rain comes it will be there,

Beyond my time, but now I take my share.

My daughter’s choice, the maple tree is new.

Come autumn and its leaves will turn to flame.

What I must do

Is live to see that. That will end the game

For me, though life continues all the same:

Filling the double doors to bathe my eyes,

A final flood of colours will live on

As my mind dies,

Burned by my vision of a world that shone

So brightly at the last, and then was gone.

Two chairs rest on Clive’s balcony overlooking the Japanese maple in his rear stone garden. He sits on one in a corner of the balcony and gazes at the maple, tufts of red leaf hinting at the fire apex it will soon bloom into.

“Usually you’re looking for ideas,” he says. “That idea was looking for me. When the thing was put into the earth it wasn’t yet in leaf. It was a long way from autumn. My daughter told me that come autumn the whole thing would be bright brilliant red. She showed me photographs of what it would look like and I got the idea straight away.”

The genius of the poem is in the half-line of every stanza. Put together, these half-lines sound like a man desperately short of breath, waiting for the autumn of his death, watching his daughter’s planted tree fill with life while losing time, losing air. Breath growing short … wheeze ... it never ends … wheeze … what I must do … wheeze ... as my mind dies.

But Clive’s autumn came, the tree bloomed and he lived. So every day is extra time. He’s already gone beyond and the beyond left him here, on this balcony, with the sun shining on tree leaves, with tropical ice blocks and kind parcel delivery men and awkward newspaper obituaries, where every great transgression and wondrous achievement finds its right place in the story.

He stares at the sturdy maple. “The void is coming,” he says. “It really is going to be a void. There isn’t anything in there. There’s no heaven, no hell. Heaven and hell are all here with us now. There’s nothing in there. You really are going nowhere.”

Some afternoons, Prue joins him here for tea. And for a moment in his mind she’s Juliet on this balcony and he’s Romeo winning her back again. It’s the most beautiful work in his book. Balcony Scene.

There is a man here you might care to save

From too much solitude. He calls for you.

“It’s true, I’m afraid,” he says of his deepest sorrow. He exhales when he speaks of it, sighs, aaahhhh. “Yes, I was a deceiver. I was faithless. I’m not now. But then, on the other hand, I’m an old man, so how can I be?” He laughs and that laugh pressures his ribs and his chest squeezes out a phlegmy cough. “But, no,” he shakes his head. “That’s a jokey answer.”

He thinks again, deeper. “I live to regret my young transgressions. But I try not to lose sight of the fact they might have been part of my youthful energy.” He thinks again, unsatisfied. “You mustn’t make that sound too glib or I will be hit in the head by certain people close to me who certainly don’t want to hear any excuses made by an artist. The artist’s standard excuse for behaving badly: ‘I need this for my art’. No you don’t. Self-indulgence is what it is.”

I’m only honest compared with other poets. They’re all dishonest.”I like his honesty. “I’m only honest compared with other poets. They’re all dishonest.”

His body aches. Mmmmmm, he squirms deep down. “I’m not sure there’s a set of literary duties but there is a set of civic duties. You have to try to be civilised. Writers should try to behave the best way possible; after all, they’re the ones who know about people behaving badly.

“Self-indulgence and severity towards others are the same vice. You’ve got to begin to be severe with yourself. The human comedy begins in your own soul. If you find everybody else funny and yourself dignified then you’re lost. I’m hard on myself. But, on the other hand, I haven’t been that hard on myself. If I was really hard I would have shot myself by now.” He smiles, if only to make his audience feel more at ease. “And here I am, living in luxury. People flying across the world to see me, what’s not to love?” He laughs.

“It’s a good topic,” he says. “Our constant balcony scene. [Prue and I] say to each other, ‘We have a combined age of 150 years’. It’s kind of extraordinary that we are still involved with each other. And it’s true. We’re … involved.”

And with that, he ambulates. Walks to the kitchen, fixes us tea. There are silences over our tea and I fill spaces with awkward and sentimental statements about how, should he go, he will be deeply missed; how, should he go, we will try to remember every word he said.

I have a long sentence for him. “Between 1986 and 1996 my mum endured every shade of life’s shit and the only man who could ever make her smile was you.” And a short one. “I wish you could live forever.”

“It’s not me who counts,” he says. “It’s what I wrote.”

And night is suddenly near. Soon he must climb up those internal stairs to his bed. There is only time enough left for an ending he has already written for me. An important set of instructions. Listen carefully. “I’m going to do a map,” he says. A map to navigate an ending. “If you walk along Circular Quay past the Overseas Passenger Terminal and go up around the bend, under the bridge, from the wall there, I think, is the best spot.” He sips his tea. “It’s from where the old ferry used to leave to go across to Blues Point. That’d be the spot.”

Let it be done in full Sydney sun. Don’t make a song and dance of it. But please be conscious of wind, lest some unsuspecting harbourside diner gets a sprinkling of Clive James with their seafood linguine.

Our dear Flash of Lightning smiles, nods assuredly. “And then I’ll be home,” he says.